Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback on Tiritiri Matangi

Author: Kay Milton and John Stewart, Biodiversity Sub-CommitteeDate: May 2024, Dawn Chorus 137Header image credit: John Sibley

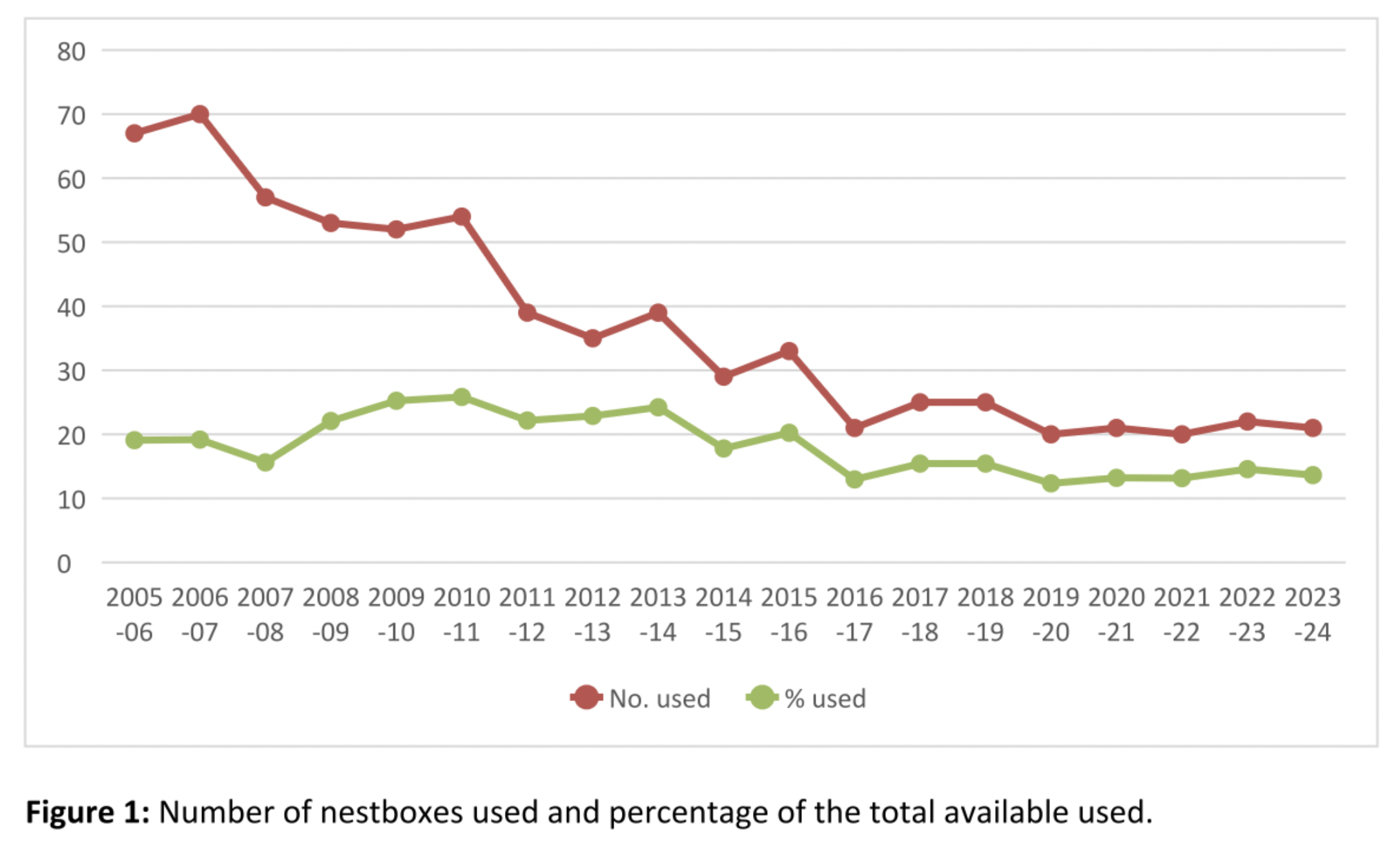

When tīeke/saddleback arrived on Tiritiri Matangi in 1984, it was truly the beginning of an era. Not only did they bring new sights and sounds to enrich the experience of anyone visiting the Island, they also marked the beginning of a project that would consume many working hours over the subsequent 40 years and which continues to this day. In 1984, only a small fraction of the original bush cover remained, and the planting programme was only just getting underway. This meant there were very few sites where tīeke could nest, so boxes were provided for this purpose. There were 360 boxes, but regularly monitoring this number proved difficult, and, as the bush planted between 1984 and 1994 has matured, an increasing number of ‘natural’ sites has become available. Between 2008 and 2012, the number of boxes was reduced to a level that could be more easily managed by a team of volunteers. Since then, it has been relatively stable at around 150-160 boxes.

Barbara was tasked with the responsibility of checking the boxes once a week during the season, and twice a week when eggs were hatching. This was quite a laborious task, which required a great deal of dedication, attention to detail, and physical exertion. Ray prepared dinner for them on the days when Barbara was occupied with checking the boxes. Barbara and Ray also used to band the tīeke chicks in the nest boxes.

Left image: Pulli 6 days old. Right image: Pulli 13 days old

Figure 1 shows that, over the past eight years, fewer than 30 boxes per season have been used by tīeke, indicating that a large majority of the birds are using natural sites. Why do we continue to provide nest boxes at all if there are plenty of other sites for the birds to use? Because, although the birds may no longer need them, they have continued to use a proportion of them each year and, in doing so, they provide us with a mechanism for observing their breeding behaviour and gauging their success. Ideally, to observe all the significant events in the life of a nest (building, lining, egg-laying, hatching, chick growth, and fledging), nest boxes should be checked every seven to ten days. This has been done consistently since 2010, with the exception of the two seasons between 2021 and 2023, when Covid restrictions and the pressure of other work made it impossible. The very welcome recruitment of eight new volunteers in 2023 has enabled regular monitoring to be resumed.

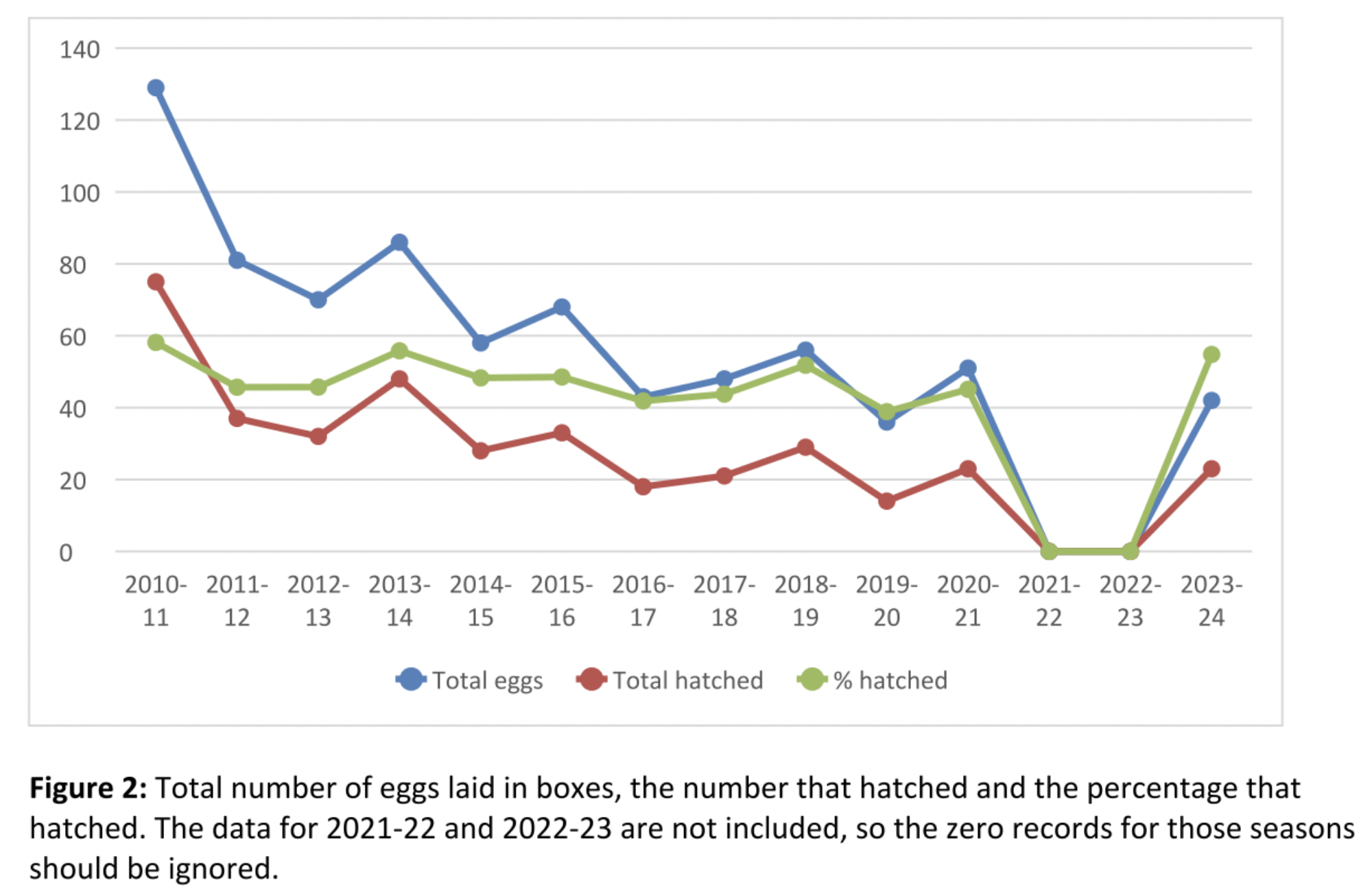

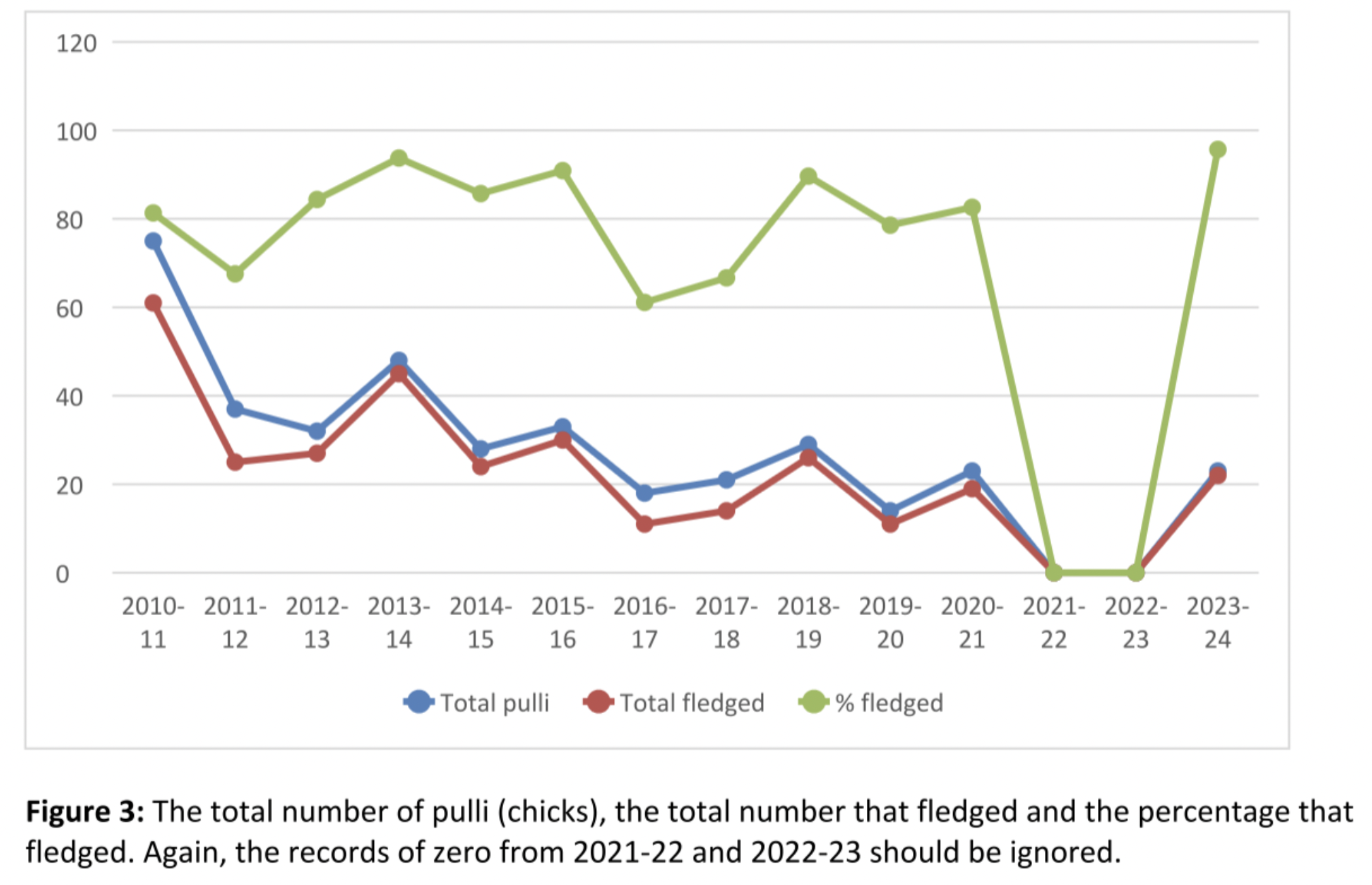

So what can we learn from the years of observation? Figures 2 and 3 are based on data from 2010-11 onwards (excluding the two seasons referred to above). They show that the numbers of eggs and chicks fluctuate from year to year but that there are longer-term trends to observe. Not surprisingly, the number of eggs laid, the number that hatch (Figure 2), and the number of chicks raised to fledging (Figure 3) have declined as the number and percentage of boxes used has declined (Figure 1). But while it is tempting to assume that this is because more natural sites are available, this is probably not the whole story.

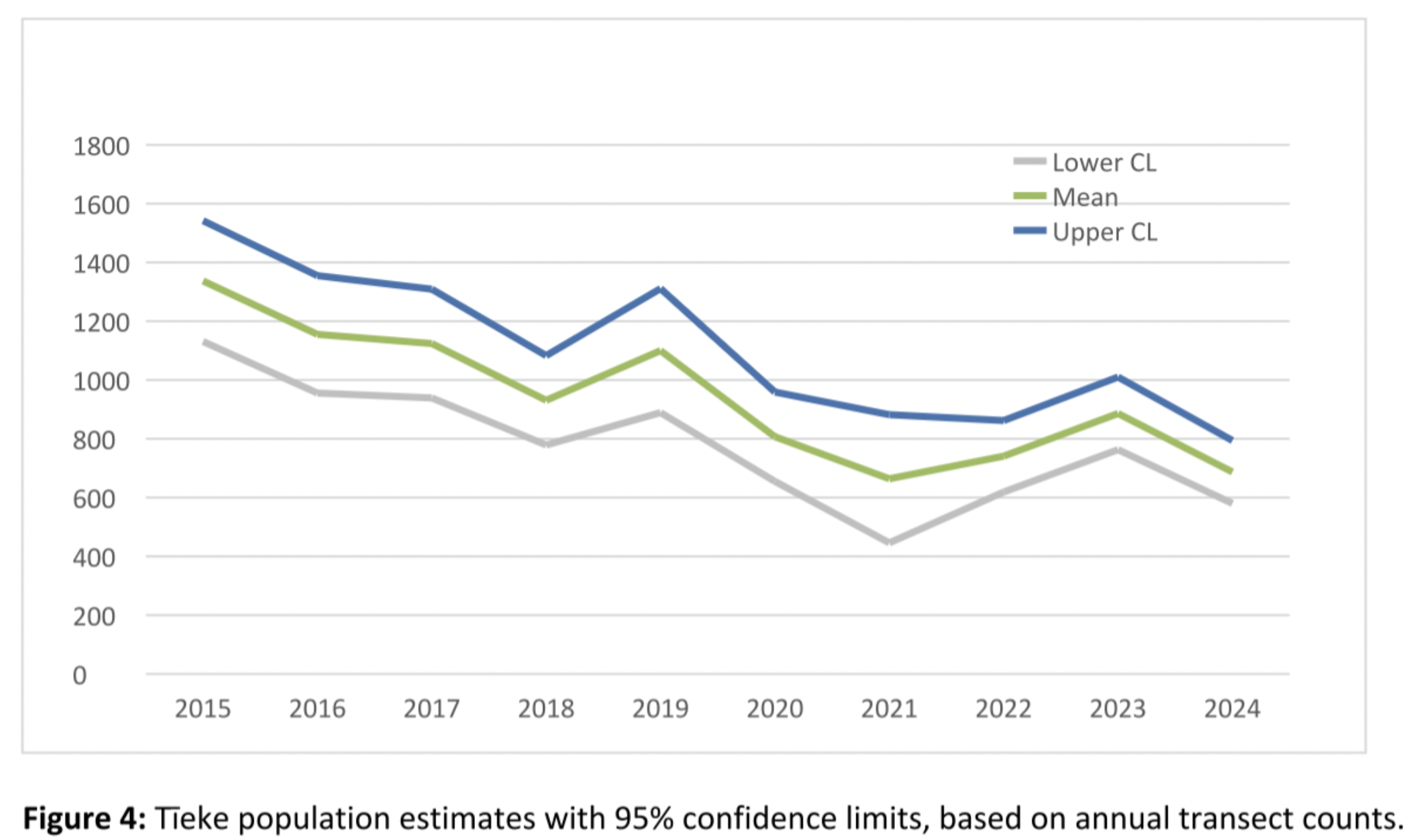

Figure 4 is based on data from the annual bird transect survey, which started in 2015. It shows that, while there have been shorter-term fluctuations, the total population of tīeke on the Island is now slightly more than half what it was in 2015. So the declines observed in nest boxes could simply be a reflection of the decline in population.

Figures 2 and 3 also indicate the percentages of eggs that have hatched and chicks that have fledged. Since 2010, 40-60% of the eggs laid each season have hatched, and a more variable 60-95% of the chicks that hatch each season have been raised to fledging. Last season (2023-24) was the most successful on record, with all but one of the chicks hatched in boxes having fledged.

It is clear from all this that the data from the nest box scheme can inform us about annual and longer-term changes in tīeke breeding behaviour and outcomes, but understanding these changes requires a much broader range of information on other components of the Island’s ecosystem. Some of this is available from Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi projects already underway (such as the transect survey mentioned above), some will come from projects planned for the future, and some is available from other sources (such as local weather records). What is certain is that, to understand what is happening to the tīeke on Tiritiri, we just have to keep checking and counting.