Maritime History

In the mid 1800s, when steam was replacing sail, and the port town of Auckland had swelled to 12,500 residents, the Tiritiri Matangi lighthouse was erected to help shipping navigate into the bustling port.

Lighthouse Museum

As the oldest operating lighthouse in New Zealand, Tiritiri Matangi holds a special place in maritime history. Constructed six years after New Zealand’s first lighthouse in Pencarrow, the lighthouse was built in 1864 in an age of shifting technologies as steam-boats increasingly entered the waters. To provide guidance for these ships, seventeen lighthouses were built during the period 1860 – 1900.

One of the lighthouses built during this time was erected on Cuvier Island, which provided light for ships entering the Hauraki Gulf from the East. The Supporters organisation was gifted this exquisite ‘first order’ light from DOC, after it was rediscovered in a shed in Pureora forest. Weighing 8 tonnes and standing at 6.5 metres in height, the light has been restored and is now in storage in a former workshop building behind the lighthouse.

To display this light properly, the Supporters have developed a plan to double the size of the workshop building and – with a view to minimising the visual impact – excavate the basement. As well as displaying this elaborate light, the Museum will tell the story of the Hauraki Gulf’s lighthouse keepers and its pre-European maritime history, through artefacts and panel displays.

Currently, there is a small makeshift lighthouse museum on the island that contains a number of maritime artefacts, so if you have a keen interest in maritime history ask the guiding manager to be shown around it.

Early Occupation

At one time the Tiritiri Matangi light was the brightest light in the southern hemisphere, visible from 80 kilometres out to sea. Mariners in the Hauraki Gulf complained of its effect on their night vision. In 1984, with the advent of improved shipboard navigational aids, the light was reduced to 1.6 million candlepower, automated and de-manned.

The last lighthouse keeper, Ray Walter, remained on the island as a Department of Conservation ranger from 1984 until he retired in 2006. Today solar panels and batteries supply electricity to a 1.2 million candlepower LED light, with a diesel generator backup.

To help guide ships into the harbour, in 1863 the Government ordered a prefabricated lighthouse from England. The 75-tonne lighthouse came in 279 packages and 3 cases, that were hauled up the hill with the help of twelve bullocks.

The third lighthouse of its kind in New Zealand, and painted dark red, it was fitted with a million candlepower oil lamp that was first lit in 1865. Powered by colza oil, paraffin, acetylene, electricity from diesel generation, a cable link to the national grid and now solar power, the lighthouse has been exposed to a number of shifting technologies throughout its 140 year history.

In 1965 an 11 million candlepower bulb was installed, much to the disgruntlement of North Shore residents who were kept awake by its powerful beam.

The lighthouse has changed radically since 1965 - it no longer contains the mechanisms that turned the small electric lights, and the eight beams of light no longer rotate. The Tiritiri lighthouse is currently the oldest operating lighthouse in New Zealand. The island's watchtower is often open to the public and contains displays of the island's maritime history including a weather gauge, signal flags, charts and historic photographs. The island's watchtower is often open to the public and contains displays of the island's maritime history including a weather gauge, signal flags, charts and historic photographs.

Sound-alarms - foghorns

The lighthouse was part of a suite of maritime apparatus used to communicate with ships coming into the harbour. Following the installation of the lighthouse, a foghorn had been used to warn ships that they were approaching land.

The first foghorn on Tiritiri Matangi was brought from Jack’s Point in Timaru. Erected in 1918, the foghorn set off percussive cartridges. It was later replaced by a diaphonic foghorn, that according to an occupant on the island in the 1960s, resembled the moan of a ‘sick cow’.

The last of the foghorns was an electronic device that was installed in 1983, however this ear-splitting warning device was eventually switched off due to malfunctioning equipment. The lighthouse keeper at the time, Ray Walter, complained that the foghorn would randomly turn itself off and on – disrupting sleep and sanity – so the Ministry of Works gave him permission to silence it.

Signal Mast

Signal flags were used internationally by ships at sea to relay short messages to those onshore.

Typically the ships would indicate via a series of flags whether a pilot ship was required, though sometimes they would contain a plea for help or assistance entering the harbour, if the boat had been in a collision.

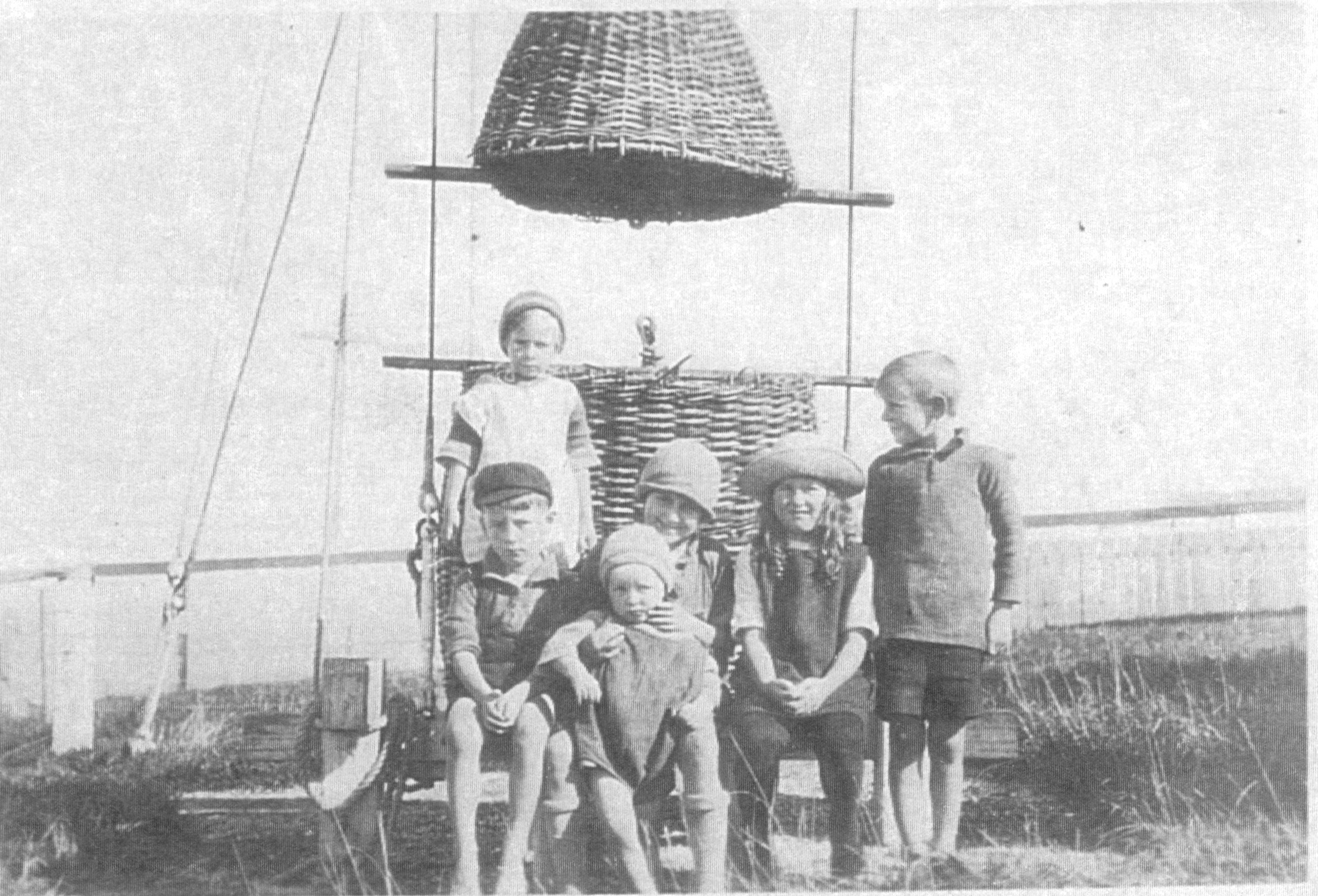

The signal mast was another piece of maritime apparatus to be placed on the island. Prior to the installation of phone lines in 1928, large wicker signal baskets were used to relay messages to the mainland.

From 1912 until 1947, it was compulsory for all vessels arriving into Auckland to take on a pilot to guide them into port. In 1947 the signal tower was closed, after this technology was replaced by radio.

Lighthouse families and signalmen

In the 1860’s, a new breed of lighthouse keepers were required to man the lighthouses that were being erected throughout the country.

Those entering the lighthouse service had strict requirements to meet. They needed to:

- be men

- be aged between 21 and 31

- have a good character

- hold a certificate from school stating their ability to read, write and have a “fair” knowledge of arithmetic.

There was only ever one woman lighthouse keeper in New Zealand, at Pencarrow Head lighthouse station, near Wellington. Although single men could apply for positions as relieving keepers, they needed to be married before being appointed to a permanent station.

The lighthouse keepers’ duties included trimming the wick of the oil lamp, polishing the lenses, and winding up the revolving mechanisms on rotating lighthouses every hour or two, to keep the light turning.

Every two years lighthouse keepers were rotated around the lighthouse stations. This way the keepers all had their turn on the more isolated stations as well as on the more popular ones.

Lighthouse keeper families were typically ex-Navy, and this strict hierarchy was carried through into island life. The families of the signalmen and lighthouse keepers met on special occasions and formal attire was required.

On the island, self-sufficiency was paramount. Typically families would keep a small menagerie of sheep, pigs, ducks, hens and cows. To supplement the families’ supplies of tinned and salted meats, the families would venture out onto the Hauraki Gulf to fish.

Trips to the mainland were rare. It was only after 360 consecutive days of working that keepers were allowed 32 days respite, during which time a reliever keeper replaced them.

Unfortunately, often the family would wind up contracting the flu while on the mainland, as they had a weak immunity to the common flu strains circulating in the community.