From the Dawn Chorus Archives: Rat tracks at Hobbs Beach spark huge effort to catch invader

Rat tracks at Hobbs Beach spark huge effort to catch invader

From the Dawn Chorus Archives

Editor: Jim EaglesDate: Dawn Chorus 112 February 2018

Photo credit: DOC and Karen O'Shea

Two huge rodent hunts have been carried out on Tiritiri over the past three months (end of 2017 and start of 2018) to preserve the rodent-free status the Island has enjoyed since 1993. Late last year a visitor reported seeing a mouse and sparked off a search which found nothing. Then early this year the discovery of rat tracks near Hobbs Beach led to an even bigger operation.

The rodent saga began on 9 November when a visitor from the US told shop volunteer Chris Eagles he had seen a mouse on Ridge Rd and later repeated the story to relief ranger Dave Jenkins. It was sufficiently convincing for the Department of Conservation to send a rodent dog to check and it smelled something interesting in the area of the sighting.

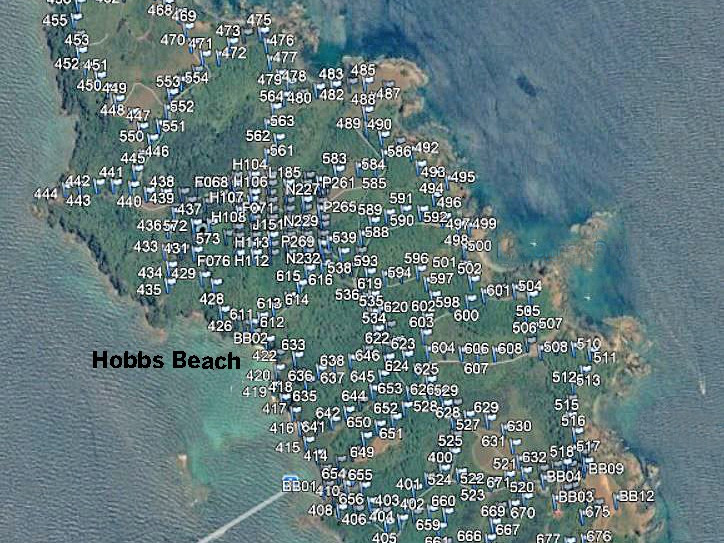

As a result, DOC set up a detection zone in a 200m radius around the site and blanketed it with devices 25m apart. These included 300 mouse traps, 500 tracking tunnels with ink pads to record the footprints of anything walking through them and 200 chew cards to record teeth marks.

In addition, the permanent rodent control network, which has hundreds of traps and tunnels set up at 50m intervals around most of the tracks on the Island, was checked more regularly. Two teams of volunteers were set up – one for Sunday to Wednesday and the other Wednesday to Saturday – to do the monitoring.

Tony Petricevich, one of the volunteers, said they checked every tunnel/trap every two or three days ‘so between us, we might work on the northern half of the Island one day, the southern half on the next and the central grid on the next and then repeat.’

Each morning there was a conference call from DOC at 9 am, ‘and then we would be given a map and list of tunnels/traps plus crunchy peanut butter in pottles or small plastic bags.

‘The tasks were simple: check tracking tunnels and traps, collect and replace cards, reset traps and rebait if required with peanut butter. The weather was very hot and dry and each of us would do up to 40 traps/tunnels, which would take us about 3-4 hours, by which time we were exhausted, hot, sweaty and covered with peanut butter and tracking card ink.’ Nevertheless, Tony said, ‘there was a great team spirit and everyone pulled together to get the job done.’

‘We didn’t see any rodent tracks, but what we did see was interesting. After being out for two or three nights many of the tracking cards, especially in damp bushy areas, would be almost black with countless weta prints. Where it was drier and more scrubby some cards would have skink prints and some might have a combination of the two or no prints at all.’

By early December, with no trace of a mouse, in between the monitoring work, the teams started to pack away some of the tunnels/traps from less accessible areas. However, Tony said, ‘We left the more easily accessible tunnels/traps in place for the rangers to collect at their leisure. As it turned out when the search was called off a few days later DOC decided to leave these out and continue monitoring. This was just as well . . .’

Only a couple of weeks later the alarm was raised again. Rangers Kata Tamaki and Vonny Sprey could only check the tracking tunnels if they had the time so when Neil Davies, one of the original SoTM mouse volunteers, was on the Island on 7 January he decided to give them a hand. In a tunnel near Hobbs Beach, which had been last checked on 1 January, Neil discovered a rat print and more prints were found in another tunnel.

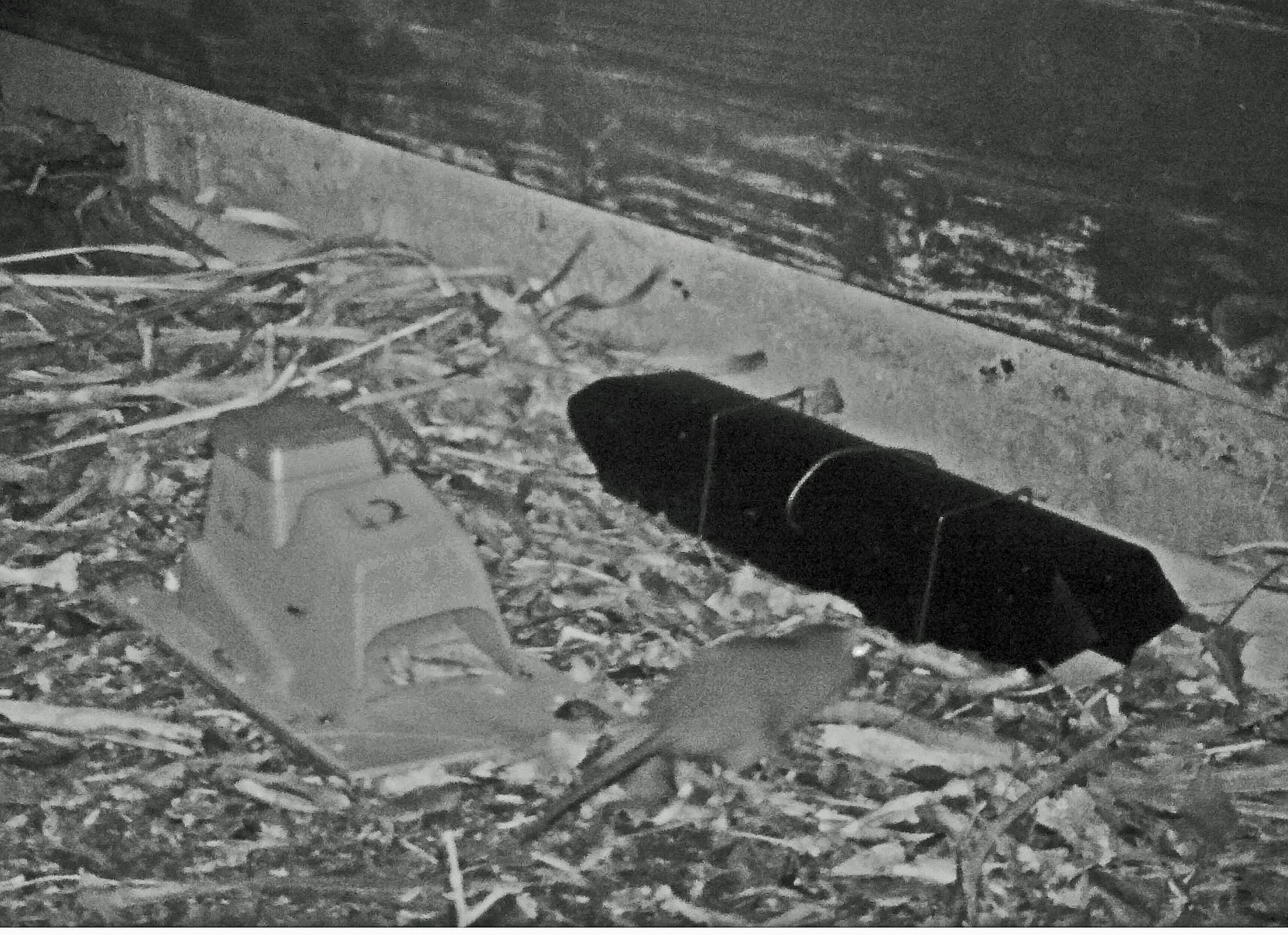

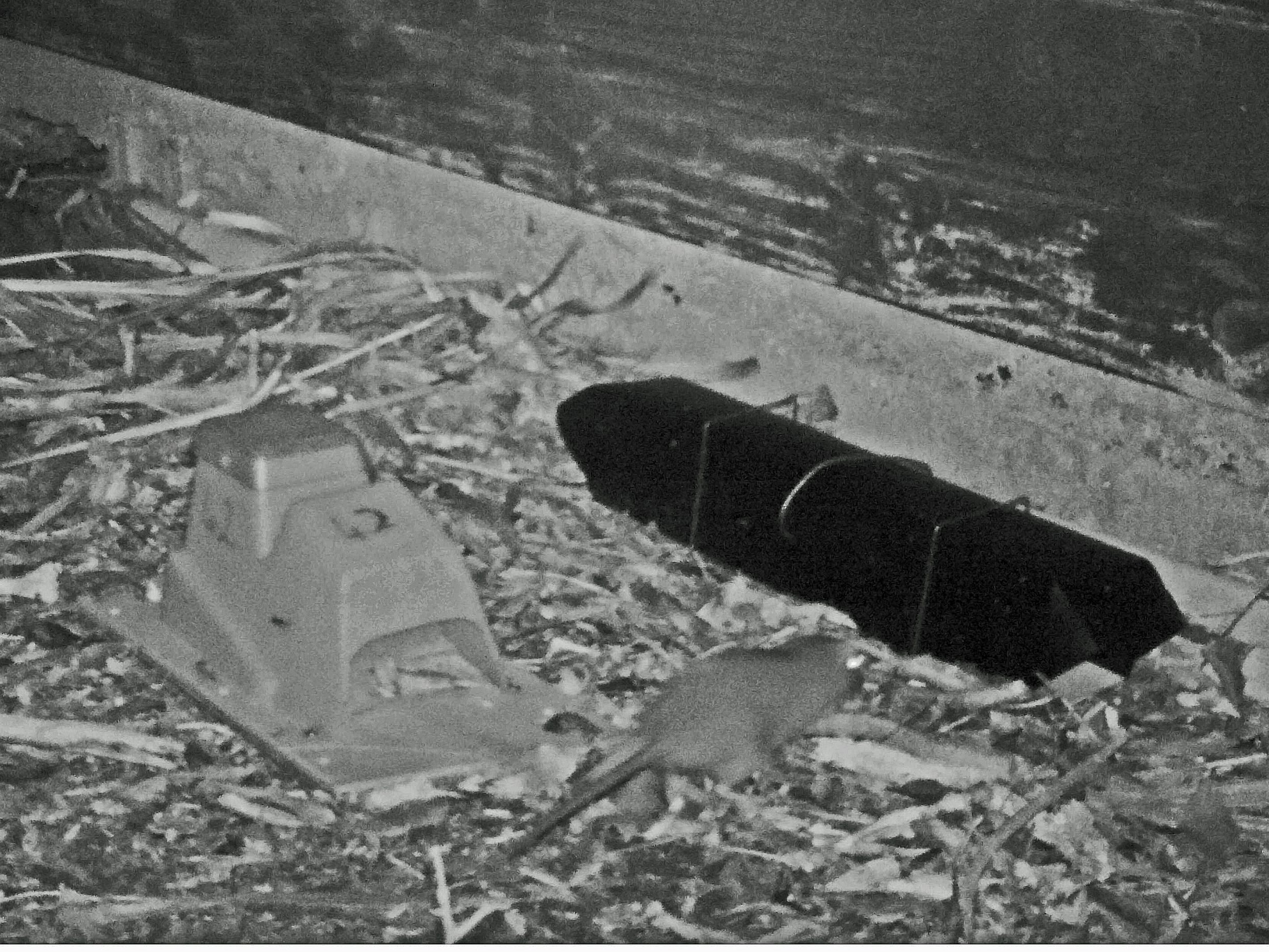

The discovery prompted an immediate and massive response. DOC sent two rat dogs and handlers to the Island and scrambled a team of officers to put out more than 50 additional traps and 60 extra tracking tunnels. This time, unfortunately, it was no false alarm. More rat prints were found in the coastal strip from the bottom of the Kawerau Track to the Wharf and further in-land at the top of Cable Rd. A monitoring camera got a photo showing a Norway rat.

Auckland inner islands operations manager Keith Gell promised: ‘The operation will continue until we can be confident the Island is once again free of predator pests.’

When the intruder initially eluded all the efforts DOC staff sought advice from experts and tried different tactics. For instance, knowing that Norway rats are creatures of habit, they put extensions on the tracking tunnels and fitted them with snap traps.

Brodificum poison was placed in five bait stations around Hobbs Beach and the bottom of the Kawerau Track and monitored daily, with the bait weighed to see how much had been eaten, and checked for teeth marks to see what had been doing the eating. To avoid disturbing the rat, visitors were urged to avoid the coastal strip around Hobbs Beach as much as possible.

The seven takahē were all penned to keep them safe from poison or rat attacks. Studies have shown that tuatara, being cold-blooded, are not affected by brodificum. However, the DOC200 traps being used were raised to keep tuatara out.

Finally, on 26 January, DOC rangers do- ing an early morning check of traps at Hobbs Beach and found a 280gm female Norway rat in a special device made by cutting a tracking tunnel in half and putting a DOC200 in the middle. Monitoring of tracks continued for a few weeks afterwards, just to be sure, and the takahe stayed in the pens for a while longer because they were due for their health checks and immunisations. But the emergency was over.

However, the fact that the rat’s footprints were first found near Hobbs Beach, where many boaties come ashore, makes it very likely that it landed from a visiting craft. The incident emphasises just how vulnerable we are and how important it is to maintain strict biosecurity precautions.

Some useful videos below to show how we can keep invasive pests off Tiritiri Matangi and why it is important to do so

Caulerpa - An invasive marine seaweed. What to look out for ... and what's next?

Caulerpa - An invasive marine seaweed. What to look out for ... and what's next?

Author: John SibleyDate: July 2023

Caulerpa brachypus and Caulerpa parvifolia are two almost identical species of invasive exotic seaweed that have been found growing intertidally on Aotea Great Barrier Island (2021) and now Kawau Island (2023). We need your help to detect it if it arrives on Tiritiri Matangi.

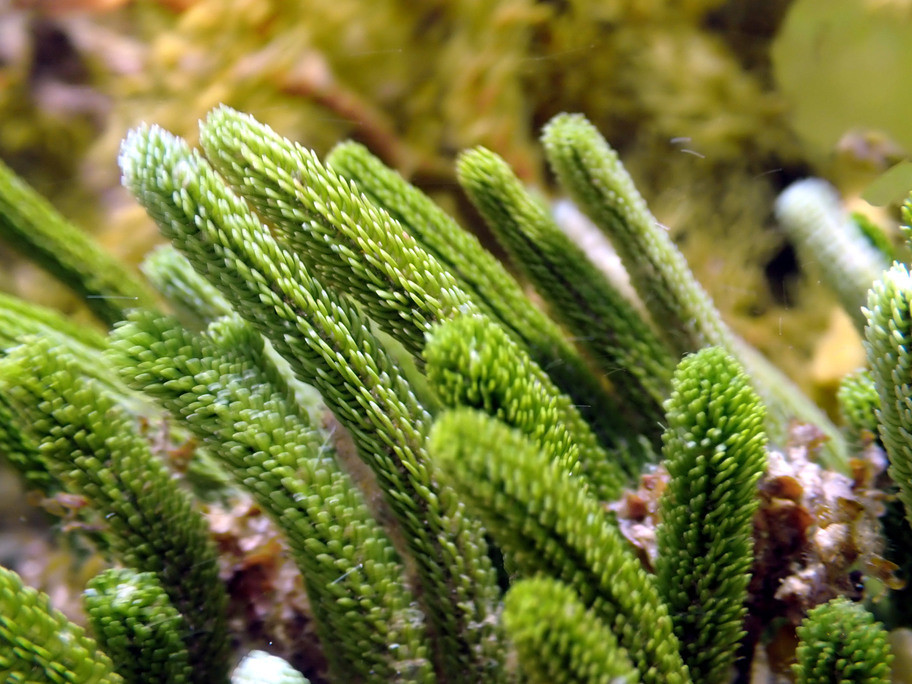

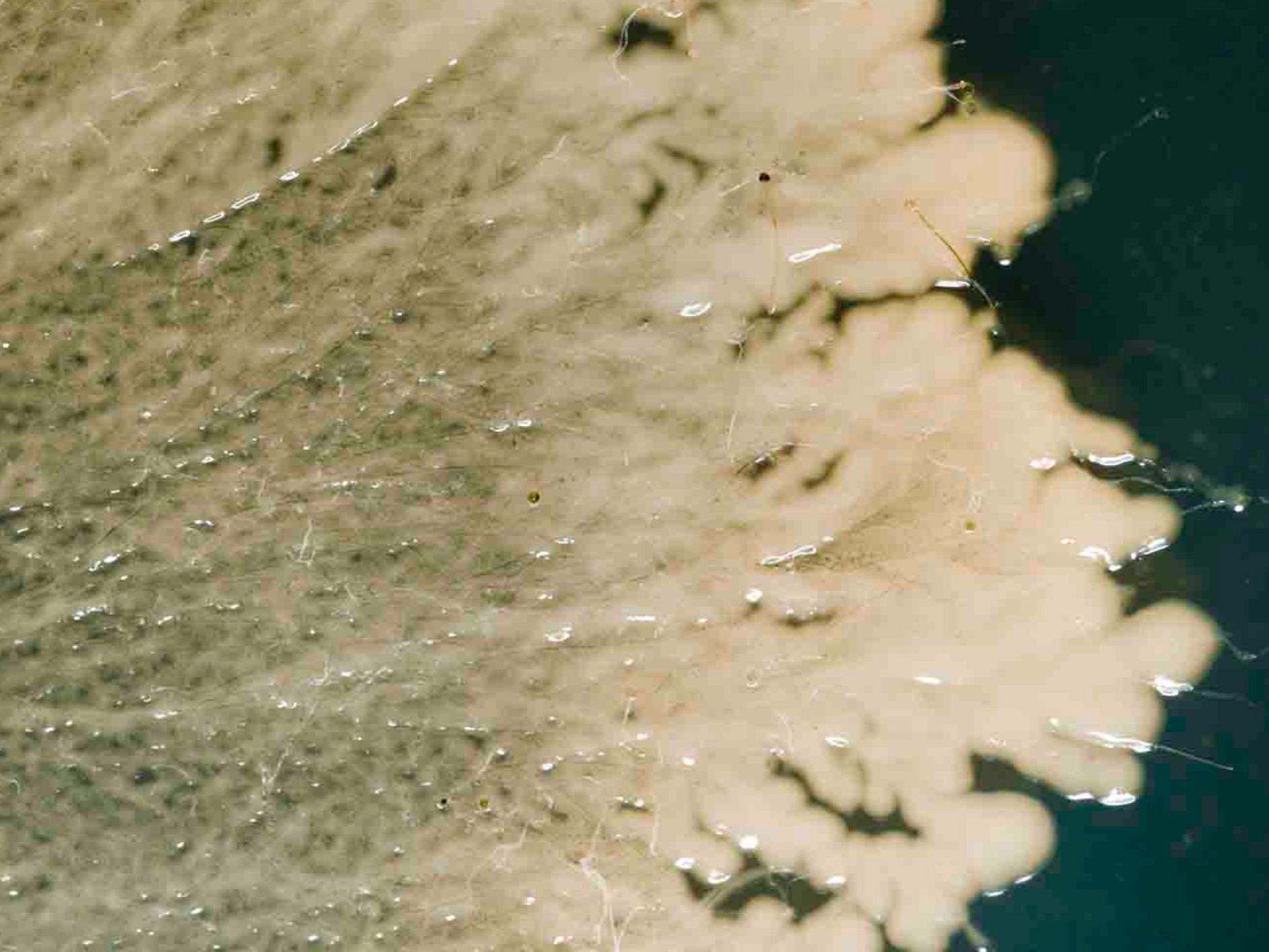

The Caulerpa species grow extremely rapidly and are said to smother everything living on the seabed. Native species either move away or die. The photos below are of C.brachypus on Aotea Great Barrier by kind permission of Jack Warden who discovered them there in 2021.

If it does establish itself on Tiritiri Matangi our Mana whenua may declare a rāhui over Tiritiri Matangi’s beaches and Biosecurity New Zealand and the Department of Conservation will impose legal controls on all boating and water activities to try and limit its spread. Whilst walking between the Wharf and Hobbs Beach please keep an eye open for this highly invasive seaweed which may be washed ashore amongst other flotsam on the tide line. You might not see it growing in situ unless it is an extremely low spring tide.

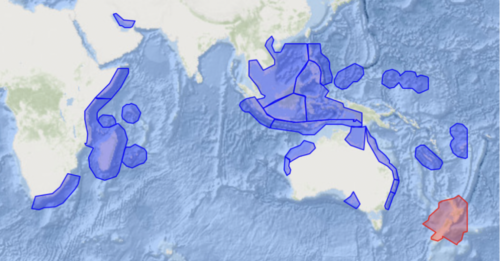

Caulerpa is a genus of marine algae with over 100 species spread widely over the Indo-Pacific region in warm tropical and subtropical seas. Most of these species are extremely variable in size and shape. In addition to the 100 or so known species, over 40 varieties are known. Many of these can also adapt and exist in more than 60 variable morphs (shapes or forms) depending on environmental conditions such as temperature and degree of exposure (wave impact). This can make precise identification difficult, to say the least.

The map above shows the current distribution of C. brachypus in the Indo-Pacific region (NZ in red). Controlling Caulerpa is very difficult due to its rapid growth rate and its ability to spread asexually using creeping runner called stolons, and by fragmentation when boat anchors or rough seas break it up.

Trials have been done using salt crystals spread onto the weed at a rate 25kg per m3 with hessian matting and tarpaulins on top to kill it by “osmotic shock” (salt essentially sucks water out by osmosis and it shrivels up). One Australian attempt involved strong chlorine bleach. Either way, as you can imagine the collateral damage to other native sea life is considerable and the week is soon back if just a small amount survives.

If you think you have discovered something suspicious washed up on the strandline, take a photo of it and report it to the rangers.

Several benign species of Caulerpa are native to New Zealand coastal waters and unlike the more recent invaders are not of concern. It would be useful to know what these native species look like to avoid any false alarms.

These photos are by courtesy of Lisa Bennett and Matt Tank.

C. articulate (first photo being held) has a feathery flat appearance, hence its other name “Sea Rimu”, but unlike C.taxofolia it has bumps or “joints” along its midrib. The thallus has side “leaves” that are also more slender than C.taxifolia.

C. brownii (second photo) has a rounded “bottle-brush” like cross-section to its thallus.

C. geminata (third photo) is our third native species and has a very distinctive thallus with “leaves” like small beads or bunches of grapes.

Of these three native species, I have only ever seen C. germinata locally, usually living in protective rock crevices at or below low water mark.

Most of the time Caulerpa species reproduce asexually by fragmentation, with sexual reproduction occurring infrequently. It seems to depend on local conditions. Some researchers found that the main plant is diploid (2 sets of chromosomes), and when sporangia are formed they release haploid gametes resulting a diploid embryo again after fertilisation. Other workers had conflicting results, finding the main plant to be haploid. However, given the extreme variation possible within each species, it is thought that perhaps they were looking at different species that appeared identical.

Some species are cultivated commercially in the Philippines as a valued seafood. Rich in iron, magnesium and antioxidants they are touted as possible treatments for heart problems and even some forms of cancer. Others are thought to be less palatable with a peppery taste. None are dangerously toxic to humans, however they are all capable of concentrating heavy metals if grown in polluted water. Some are grown as nitrate absorbers on fish farms, where periodically the weed is harvested and spread on the land as fertiliser.

Caulerpa is unusual in that they are syncytial, not multicellular organisms (left). The entire plant or colony could be looked upon as one enormous cell, with many nuclei scattered throughout. The cell membrane forms the outer “skin” of the thallus. Interestingly, if the thallus is cut, the cytoplasm does not leak out, but instantly forms a new cell membrane at the site of the cut. Enormous numbers of microtubules are present in the cytoplasm, and these are thought to give the thallus its shape. Indentations of the inner part of the cell membrane extend deep into the thallus and these could aid the diffusion of nutrients in, and wastes out of the thallus. Their explosive growth rates bear witness to the effectiveness of these various adaptations.

Their negative impact on the ecology of the seabed does seem to vary according to the species of Caulerpa involved, and the geographic location of the invasion. The Mediterranean has seen one of the worst invasions of what is thought to be the most pernicious of this genus – Caulerpa taxifolia. Strangely though, its presence has seemingly had little effect on Posidonia oceanica the resident seagrass there. Will our own native seagrass Zostera meulleri stand up to an invasion by C. brachypus?

Other published studies have shown that in French and Italian Mediterranean waters fish diversity and biomass are equal or greater in Caulerpa meadows than in seagrass beds and that Caulerpa had no effect on composition or richness of fish species. It all depends on whether the fish species present can use the Caulerpa species as food source or not. Shellfish beds have been particularly hard hit, with many long established sites smothered and destroyed in many parts of the world.

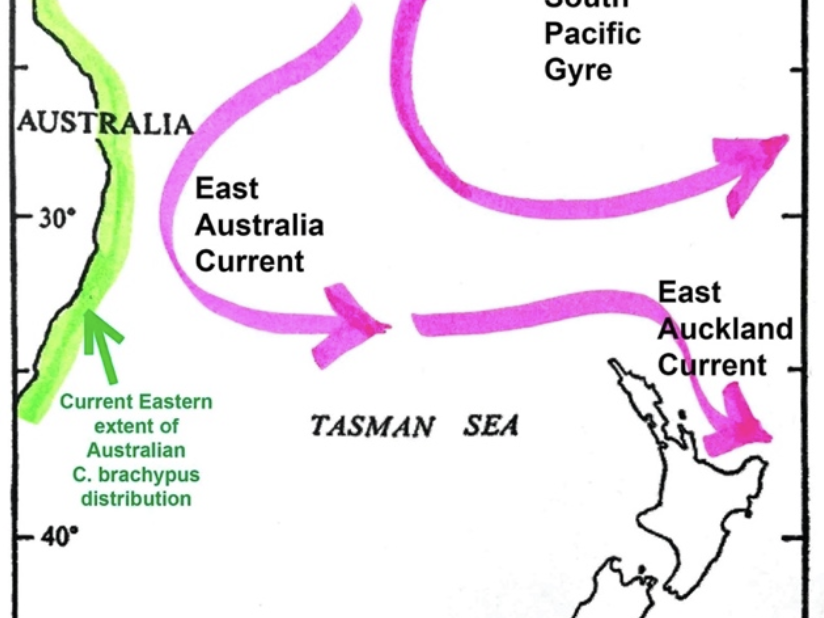

The two new species – Caulerpa brachypus and Caulerpa parvifolia we have here in New Zealand probably originated from the eastern coast of Australia, 2,200km away to the west. The main vector would have been ocean currents and tides.

Boating and fishing activity are thought to play a significant role spreading fragments of weed between nearby locations within New Zealand.

It takes only a small fragment to create an immense smothering bed in a few years. The South Pacific Gyre dominates the ocean circulation in the South Pacific. Driven by the trade winds and Earth’s rotation, warm equatorial surface water swings down from the northeast against the coast of Australia. Eddies detach forming the warm East Australian Current which can carry Caulerpa fragments from the east coast of Australia across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand. Here it forms the East Auckland Current which delivers subtropical water to the northeast coast of North Island and the Hauraki Gulf.

The reason why these exotic species have only recently become established here in Auckland is that until recent decades, the sea temperatures here have been too cold for them to become established.

This July the seawater temperature off Tiritiri Matangi has been consistently between 3.5 to 4 oC warmer than it was compared to records made 50 years ago, possibly allowing these drifting exotic fragments to survive, settle and become established. Increasing nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the Hauraki Gulf from Auckland’s sewage will also stimulate the growth of algae living there.

Although all the Earth’s oceans are interconnected, it is temperature barriers that often set biogeographical limits for many marine species. For animal species that spend a few weeks drifting as planktonic larvae, time is also a barrier preventing them from travelling very far on ocean currents. The Mediterranean fan worm is a good example of an organism whose distribution is limited by both temperature and time. Their tiny larvae do not stay suspended in the water column for long enough to travel very far, before dropping to the bottom to attach as adult sessile fan worms.

This wasn’t a problem until the advent of rapid ocean travel allowed them to get as far as New Zealand in ships ballast tanks or as adults fouling hulls. Travelling on ocean currents alone might have taken them years or decades. Oceanographers studying ocean currents became very excited when in 1992 a container ship heading to the USA from China shed 29,000 yellow plastic bath ducks into the sea during a storm. These eye catching objects were found on every shoreline around the Pacific within 4 months. Some were carried north where they were trapped in Arctic ice, and they eventually emerged in the North Atlantic where in 2007 some were washed up on the coast of Ireland and Spain.

Although Arctic temperatures and time would have killed any living organism undergoing this 15 year marathon, it shows how the world’s oceans are all part of one system and the hop from Australia to New Zealand is not such a big deal.

All this does rather beg the question – how long will it be before MORE exotic species drift into our invitingly warm waters and set up home here? Caulerpa taxifolia is already established in the coastal waters off NSW in Australia.

We need to keep alert!

What could possibly go wrong?

In the 1970’s a team of biologists from a southern European marine institute set about breeding a cold-tolerant form of perhaps the most rampant species, C. taxifolia. It was bred for their museum aquarium displays and the home marine aquarium trade rapidly acquired some. Inevitably perhaps, C. taxifolia escaped in the Mediterranean Sea and has been dispersed far and wide since then causing untold ecological damage.

C. Taxifolia broad lateral “leaves” that distinguish it from our own similar native species C. articulata. It is NOT in New Zealand waters… yet.

Photography Walks

Tiritiri Matangi Photography Walks

Join the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi for a Guided Photography Walk - a unique experience for anyone with an interest in photography visiting Tiritiri Matangi Island

Capture the magic of Tiritiri Matangi Island through the lens on these special walks with an experienced Supporter of Tiritiri Matangi Island photographer.

Duration: 2 hour guided walk

2025 dates:

Saturday 29 March

Saturday 12 April

Saturday 26 April

Saturday 3 May

Pioneering restoration of Tiritiri Matangi

The pioneering restoration of Tiritiri Matangi

'Saving Britain's Island' is a short film about island conservation, by ZSL PhD student, Joshua Powell. Produced by Matt Jarvis with the assistance of camera operators Benjamin Harris (UK) and Ben Sarten (NZ)

Funded by the British Ecological Society

In early 2021 a film crew from the UK visited Tiritiri Matangi to produce a short documentary. The film would target audiences in the UK as an introduction to island conservation. Tiritiri Matangi was chosen because the pioneering restoration project has inspired similar projects around the world. The film explores how these techniques can be used to help protect biodiversity in the UK Overseas Territories.

If only we could re-live those days

If only we could re-live those days

Author: Mrs Dora Walthew (nee King)From the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi archives. We think it was written in the 1980s

It was the year 1934 and the island sat like a bright green jewel, in the blue waters of the Hauraki Gulf – approximately 16 miles from the port of Auckland, which nestles beyond the massive bulk of Rangitoto, guardian of the harbour entrance. The island was fringed with the bright red blooms of the pohutukawa trees, growing from the cliffs edges and along the rock foreshore.

On the highest point of the island, stood the lighthouse. A 60 foot construction of steel sections, bolted together with a strong beaming light which flashed warnings to the shipping, entering either of the two passages to Auckland.

Two keepers’ homes were built on the flatter sides of the hill and another house of superior construction was built further over, close to the cliff edge. (Where the bach is today). This was the home of the head keeper. Large concrete tanks were constructed alongside each home, for the island dwellers depended on every drop of rain that fell for their water supply. With various sized implement and storage sheds and a stable to keep chaff and oats for the station horse, there was quiet a community of housing.

A large red gate connected to a seven wire fenceline, running the width of the island and another fenceline running the length. This separated the station land from the rest, which was leased to a farmer (Hobbs) on the Whangaparaoa peninsula.

Sheep and cattle were run on this land. Through the red gate, the station horse named John, pulled the grey konaki every Thursday fortnight on his way to the wharf, about a mile and half distance. Slipping and sliding with an empty slepdge on the way down and heaving and pulling the heavy load back up the hills.

This was boat day and a holiday for all, except the man on duty. The island population would proceed to the wharf to extend a welcome to all on board. Sometimes, visitors would climb the hills to visit the lighthouse and the launch would stay for about three to four hours. They would enjoy the hospitality of the wives, who usually made a batch of scones and offered a welcome cup of tea. Often, lasting friendships came from these visits. If the house cows were producing well, the visitors went from with a jap of real, thick country cream and memories of a really great day – and a little envious of the island dwellers.

For the families, it was the excitement of unpacking the stores and putting everything away in the big storeroom which each house had. Sometimes, Messrs J. Jones sent a packet of sweets for the children and this was a rare treat.

This was the day the family had fresh meat for tea, as there were no refrigerators. All other meats had to be put down in brine. All the family shared with the unpacking and putting away the goods. Tinned meats and fish. Large sacks of flour and sugar. Dried fruits, cereals, dried peas, rice, barley, tea and coffee. Seven pound tins of treacle and golden syrup, flour and half a pound tines of biscuits.

A large side of bacon which was hung from the pantry ceiling, from which slices were cut off as required. A paste of flour and water was then placed over the cut to keep it fresh.

When the task of putting away the stores was done, the next task was the undoing of the school envelopes, to see just how many mistakes one had in their set. Also, to read the remarks from the teachers in Wellington. The families were taught by their mothers and made good progress with their schooling.

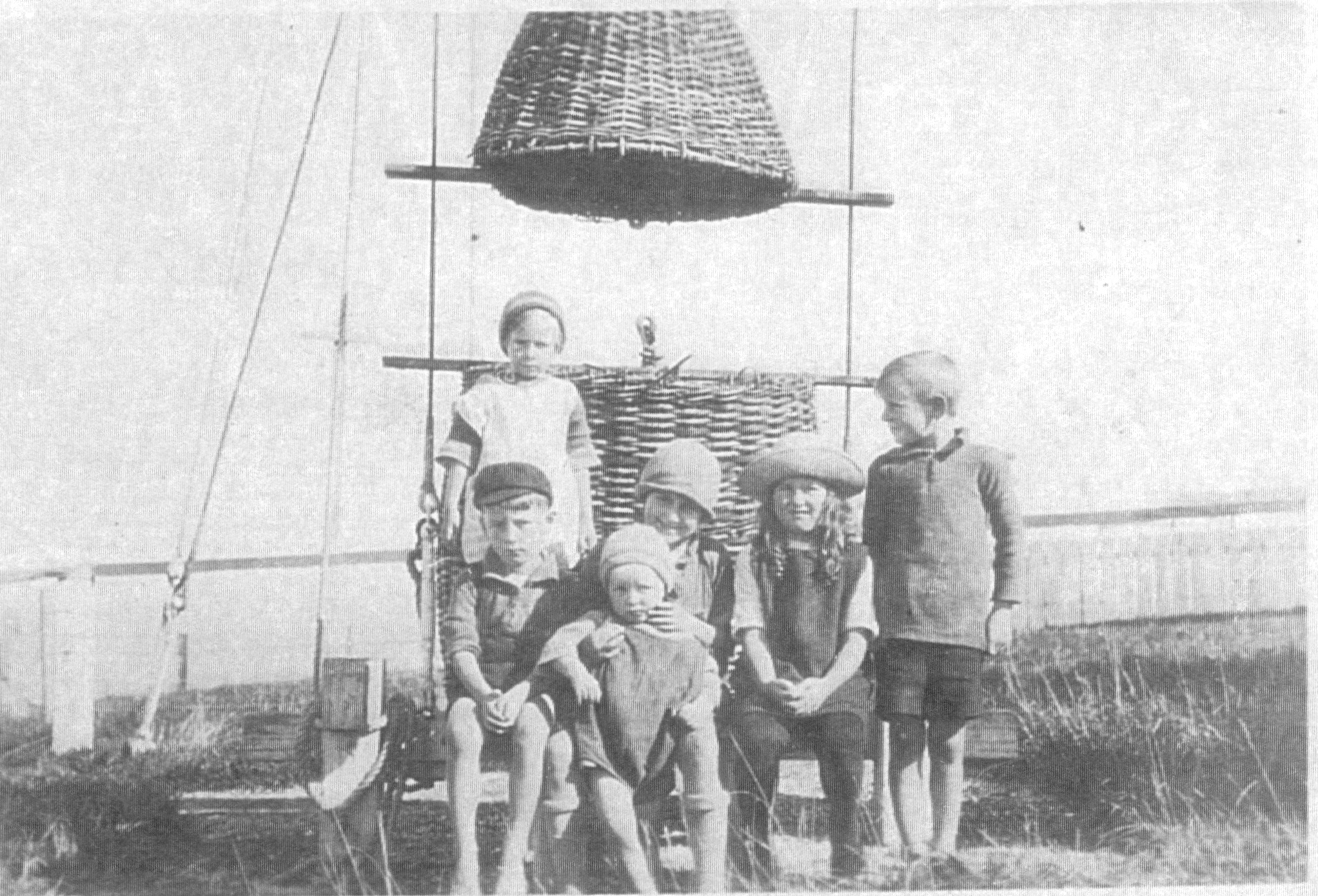

This day, three of the five children belonging to the third keeping (Alfred King), swung on the red gate. The time was fast approaching when they would leave their beloved island. They felt sad, but with the natural resilience of children, soon began making plans for the future.

The eldest boy (Alf), spoke first and said he wanted to fly a plane and become an engineer. He was a grey-eyed, fair boy with a quick mind and natural bent for anything mechanical or electrical. He was their leader and the two children adored him. They followed him like well drilled soldiers.

The next boy spoke (Reg). He was a dark haired and happy natured child. He was going to America and wanted to dance with Deanna Durbin who sang so beautifully.

The third member of the party was a fair headed, skinny girl (Dora), who could have passed for a boy with her close cropped hair.

This day she was clad in her brother’s navy shorts and grey shirt. She wished fervently to become a boy. If only God would transform her, she would be so happy. She bitterly resented being born female. She loved to be outside with the fowls, calves and cows and adored all forms of nature. But, indoor chores were hated – especially dishes – whenever it was time to dry them, Mother Nature called and when she returned, they were all thankfully done and put away. In repair, her mother gave up trying to make her ladylike and she ran wild with the two elder boys. She was delegated to milk the cows and clean the fowl house. These jobs she did with joy, as to her, the animals and birds were real people. She seemed to have an affinity with all nature and determined to fiercely independent.

Only three years separated these children and they were not only close with blood ties but with a deep bond of affection and loyalty for each other. They would not hesitate to lie to protect each other from a whipping.

Their father, an ex naval man, was a strict disciplinarian and with his quick temper, never listened to explanations or excuses, so it did not pay to tell the truth, as one still got chastised.

They were strong willed too and although they listening to his lectures on the dangers of cliff climbing and the sea, the advice was forgotten as soon as they were out of ear-shot.

No cliff was too steep to attempt to climb, in spite of the dangerous rocks below and the terror of falling. On more than one occasion, they had taken the twelve foot dinghy from the boat-shed, pushing it along the wharf and lowering it by crane to the sea below and rowing out to the reef where the gulls nested. It was wonderful to hold the tiny grey and white spotted chicks, with the angry parents dive-bombing above their heads. On these occasions, they were never caught, mainly because the boat-shed and reef were not in sight of the station.

None were more skilled at stealing provisions from mother’s larder – dried apricots, packets of lushus jellies, jars of pickles and jams and biscuits – also slices of cheese. These were carefully hidden in their clothing and secreted away to their hut at the end of the island. (They were sure mother knew, but she never complained about the loss – and in later years told them she felt they had had enough whippings).

What great adventures these three had there, with their imagination running wild and not a soul to disturb them and their fantasies. They became expert at collecting fat mussels when the tide was low and also rising the oysters from the rocks, which they cooked on the beach. The swimming nude in the rock pools and catching fat shrimps. Another favourite past-time was beach-combing and many wonderful treasures were collected. Sometimes plates from passing steamers, found their way ashore and these were carefully placed on the rocky shelves in the driftwood hut.

Occasionally, father’s garden in the gully was raided and fresh young carrots and white turnips were taken out to the hut, to eat with the cooked mussels. These were dished up on treasured plates. Every inch of the island was known to them and it was great thrill to find the glass balls, which came ashore from the fishing trawlers.

Small pockets of bush grew in the gullies and many varieties of birds lived there. They loved holding a stick out for the friendly black fantail to sit on. Hours were spent decorating the fresh cow-pats with yellow and white daisies and dock seeds, making intricate patterns.

The boys had jobs to do too. Cutting kindling wood and ti-tree for the big kitchen range and the hated job (usually done on a wet day), of emptying the toilet tin over the cliff edge. They would put a stout stick through the handle and clad in grain-sack hoods, the sack corners turned in – they proceeded like monks down the paddock, carrying the offending matter to the edge of the cliff.

In the evenings, the copper would be boiled and baths taken in the big, wooden wash-tubs. One child in each tub, with the warmth from the copper making the wash-house so cosy, then across the yard, into the house for tea. Later, into the front room where the wonders of good books could be enjoyed.

Their parents did not spare themselves to buy good, wholesome reading books. Stores of distance lands and people and travel books. The National Geographic books were avidly read again and again and a wealth of knowledge was gained and remembered.

With the fresh air and fresh caught fish and the vegetables, their bodies and minds were healthy and their energy and imagination boundless.

Fifty years later, a man and a women by the red gate. A brother and sister – the eldest brother had long since passed away, after flying an aeroplane and becoming a precision engineer. They look up at the lighthouse with tears in their eyes, as their thoughts nostalgically go back through the years.

The man speaks first, with an Amercian accent. “You know sis, coming back to our island home after 50 years, has been the highlight of my trip back to New Zealand. What a wonderful childhood we had. If only we could re-live those days. Its sad our brother is not with us. You know, I did dance with Deanna Durbin too.”

“Yes,” said his sister. “Both of you boys got your wish – I did not get mine – if only.”

To find out more about Tiritiri Matangi history why not buy Tiritiri Matangi: A Model in Conservation by Anne Rimmer

How to attract native birds to your garden

How to attract native birds to your garden

Author: Toni AshtonDate: July 2023

Photo credit: Andrea Tritton

Its been wet, windy and chilly on Tiritiri Matangi lately and so the nectar-feeding birds – i.e. tūī, hihi/ stitchbirds and korimako/ bellbirds – have been busy at the feeding stations, providing great entertainment for visitors.

Providing food is just one way of attracting native birds to your garden. You can also plant native trees and shrubs. And providing patches of leaf litter or mulch will help to attract insect-eating birds such as the pīwakawaka/ fantail and tauhou/ silvereye.

In summer, a shallow bird bath provides water for drinking as well as a nice cool bath for the birds. And of course the birds need to feel safe and so trapping predators such as rats and mice, and keeping cats away from your garden will also help to attract the birds.

The websites of the Department of Conservation and Forest and Bird provide excellent information about which birds eat what, which trees and shrubs to plant, how to keep the birds safe and many other useful tips.

Kōkako Banding on Tiritiri Matangi

Kōkako Banding on Tiritiri Matangi

Author: John StewartDate: 30/06/23

Photo Credit: John Sibley

The kōkako population on the island has been closely monitored since the first birds were brought here in 1997. Ten years later, the island received the captive-bred descendants of the last wild birds living in Taranaki. It was hoped that they would survive and breed on Tiritiri and eventually their descendants would be returned to their ancestral home. The birds were banded so that it would be possible to record their family trees and keep track of their relationships. That hope was fulfilled in 2017 and 2018 when birds were returned to Parininihi and Pirongia.

We have built on that initial work, continuing to band and to record details of the individual birds and their lives on the island resulting in a unique long-term data set which we hope will be used to better understand and to protect and sustain them.

Trained banders give each bird a unique combination of one numbered metal band and up to three plastic colour bands allowing observers to recognise each individual. Most of the birds are banded as chicks before they leave their nest.

Tiritiri Matangi kōkako bands

Te Rangi Pai enjoying some water

Sharing the love: where are the takahē now?

Sharing the love: where are the takahē now?

Author: Phil Marsh, the takahē sanctuary sites ranger with the Department of ConservationDate: June 2023

Heading photo credit: Malcolm de Raat

This certainly isn’t an exhaustive list but it highlights the contribution that takahē from Tiritiri Matangi continues to have on the programme to increase the population throughout the motu. It also demonstrates the fluidity of the takahē programme.

2009 – Apiata was removed off Tiritiri Matangi and transitioned to the Murchison Mountains. He is still alive there to this day and has produced juveniles with his partner, though the number is unknown. He is a great example of how well takahē from sanctuary sites can transition, provided they receive the necessary training at Burwood Takahē Centre prior to being released in the wild. I’ve seen him in the Murchison Mountains around six times since being involved in the programme and I have a real soft spot for him.

2010 – Wal was moved to Burwood as a breeder from 2012-2021 and raised a number of juveniles (four juveniles in 2018-2020 alone). He was shifted to a privately-owned sanctuary in the South Island in 2021 where he is paired with a new partner to this day.

2013 – After leaving Tiritiri Matangi, Pukekohe spent time at Tāwharanui Regional Park where he was part of a breeding group, although he was never successful at raising a juvenile. Today he is on Mana Island and has successfully paired this season. They produced two chicks, his first to date.

2014 – Jenkins has been at Burwood for a number of years now as a breeding female. Since 2018 she has produced five juveniles.

2016 – Turama was moved from Tiritiri Matangi to Burwood for a number of years as a breeding male. Since 2019 he has produced five juveniles.

2017 – Waimarie transitioned through Burwood, paired up and was then sent to Orokonui Ecosanctuary in Dunedin. Last season she produced her first two juveniles, which are being trained for release into recovery sites. This season she produced two more chicks.

2017 – Kahuhura is now paired on Mana Island and has finally produced two chicks this season, his first to date.

2018 – Hana was sent to Mana Island (where she has paired up with an offspring of Turama) and produced her first juvenile last season.

2018 – Mira was sent to Motutapu Island where she was seen with a partner recently. She has no juveniles to date as far as known

2018 – Te Paea transitioned to Burwood and was released in the Murchison Mountains in 2019. A colleague and I saw him in a territory with a partner during the 2020 census, showing that he had settled into the site.

2019 – Te Marino was sent to Cape Sanctuary at Cape Kidnappers and paired with the single male there. They had breeding attempts during the last season but were unsuccessful.

Other incidental takahē related to Tiritiri Matangi: Fyffe (breeding female on Rotoroa Island) is one of Wal’s offspring. She has been a successful breeder the last few seasons. Walter (male on Motutapu Island) is one of Wal’s offspring. Hogan (male at Willowbank Wildlife Reserve) is one of Jenkins’ offspring.

Children energised by the wonders of the New Zealand bush

Children energised by the wonders of the New Zealand bush

Author: Jean GoldschmidtDate: 18/05/23

Winter clothes today; boots, long trousers and the raincoat at hand for the dank, dark miserable day. White horses whipping up the waves found the ferry rolling sideways and passengers glued to their seats. Sitting indoors for a change, I smiled and added comments to the conversation between guides but my mind was on the children we would be guiding today. Was I over it? Did I really want another dose of young children? Already in their groups the children came off the boat and lined up on the concrete in a manner which showed thorough preparation – so a good start.

Away as group four, I marched up the path with eight ten-year-sold and the teacher behind me. She explained the children were in three groups, birds, environment and she took the māori component but she felt she still had a lot to learn. With full participation, they quickly found all the berry colours on the tawapau. After the constant rain, all heard the gurgling water rising up the māhoe. Everyone found a perfect skeleton leaf which they matched with a green living leaf. At the edge of the bush, the pōpokotea/ whiteheads flitted back and forth over our heads until one briefly landed on the track in front of us. These special little birds with heads dipped in white paint move in families and whisper loudly to each other. But today, the tīeke had monopoly over the ground feeding. When we were on the rise and ahead of two groups on the shortcut, our group turned to see a kererū resting on its own, before it suddenly took off don’t the track towards the wharf. Being higher we had a great view of the two groups ducking and laughing as the kererū flew into them. How no one was knocked over by the flying bird will remain a mystery to most of us but the scientists have studied the extraordinary eyes of birds.

These fabulous children knew the story of how the tīeke got its brown saddle and at the hihi nesting box one girl told us that the female finds all the base sticks with the male contributing a couple. Then using her body to demonstrate she stood tall, puffing out her chest she imitated the male hihi calling “Look at the fine nest I have built”. Seeing the actual nest she brought her story to life. At lunch, another guide Neil began telling the same story told to him by the headmaster who walked with his group. Neil promise to tell the teacher we guides thought a great job had been done in preparing the class for the Tiritiri trip. At the pūriri tree another child said how a teacher had shown them a real pūriri moth and again that child related the story. To have children really energised by the wonders of the New Zealand bush brought home to me how teachers can inspire learning. This delectable group, which now once had to be told to stay on the track, with a motivated teacher, so keen to learn and share left me in high spirits. These enquiring minds completely washed away the morning’s doubts.

Returning down the shortcut alone I bush-bathed, enclosed by life-giving trees I absorbed bird calls filtered by smells and silence. Wonder of wonders. I emerged renewed.

Ancient Tiritiri Matangi: Adventures in "Deep Time". The Fungi

Ancient Tiritiri Matangi: Adventures in "Deep Time". The Fungi

Author: John SibleyDate: 16/06/23

We have been travelling through “Deep Time” from the dawn of Earth’s history when living things first appeared, some 4,000,000,000 years ago (4,000Mya or 4Ga). It is thought the Fungi evolved about 410Mya just before the land was colonised by plants. Today they form one of the most diverse kingdoms with varied ecologies, lifestyle strategies and morphologies (outward shapes). Their members include single-celled yeasts, filamentous fuzzy moulds and familiar mushrooms. Although once classified with the plants, they share more features (including genetics) with the Animal Kingdom.

Part of our fascination with fungi is that they have a secret “hidden life” in the earth beneath our feet, emerging above ground only to disperse their spores into the air – popping up overnight as a wonderful variety of “fruiting’ bodies. Some of these “mushrooms’ are very poisonous to humans while others are delicious to eat! Yet other fungi raise our bread, brew our beer, flavour our soy sauce and cheese, and cure our ills (antibiotics and statins etc.)

It is estimated that this hidden fungal horde with their vast subterranean network of feeding threads at least equals and perhaps exceeds the biomass of the more visible Plant Kingdom that lives above them in the world of light. The only time you might notice this hidden world is if you disturb a mouldering piece of branch on the forest floor when raking leaves off the track. The tufts of white threads (hyphae – collectively called a mycelium) visible where the branch touched the earth are a sure sign these rotters are at work!

Unlike plants their cell walls are composed of chitin (Pron. Ky-tin) used in arthropod exoskeletons and Mollusca “teeth”. None are photosynthetic, instead feeding heterotrophically like animals. They do this by exuding digestive enzymes from their hyphae externally onto their food material and absorbing the digested products. Whilst walking, you might see a powdery rotted piece of a tree branch on a track. It has been digested from within by the fungal threads that once permeated it! In this way, the fungi perform the extremely important task of recycling nutrients in the forest ecosystem as decomposes.

Growth is their only method of movement, apart from microscopic spores which can be blown far and wide in global weather systems. For this reason, many native NZ fungi also have a worldwide distribution. Many fungi will invade living plant (and animal) tissue as pathogens (disease causing parasites).

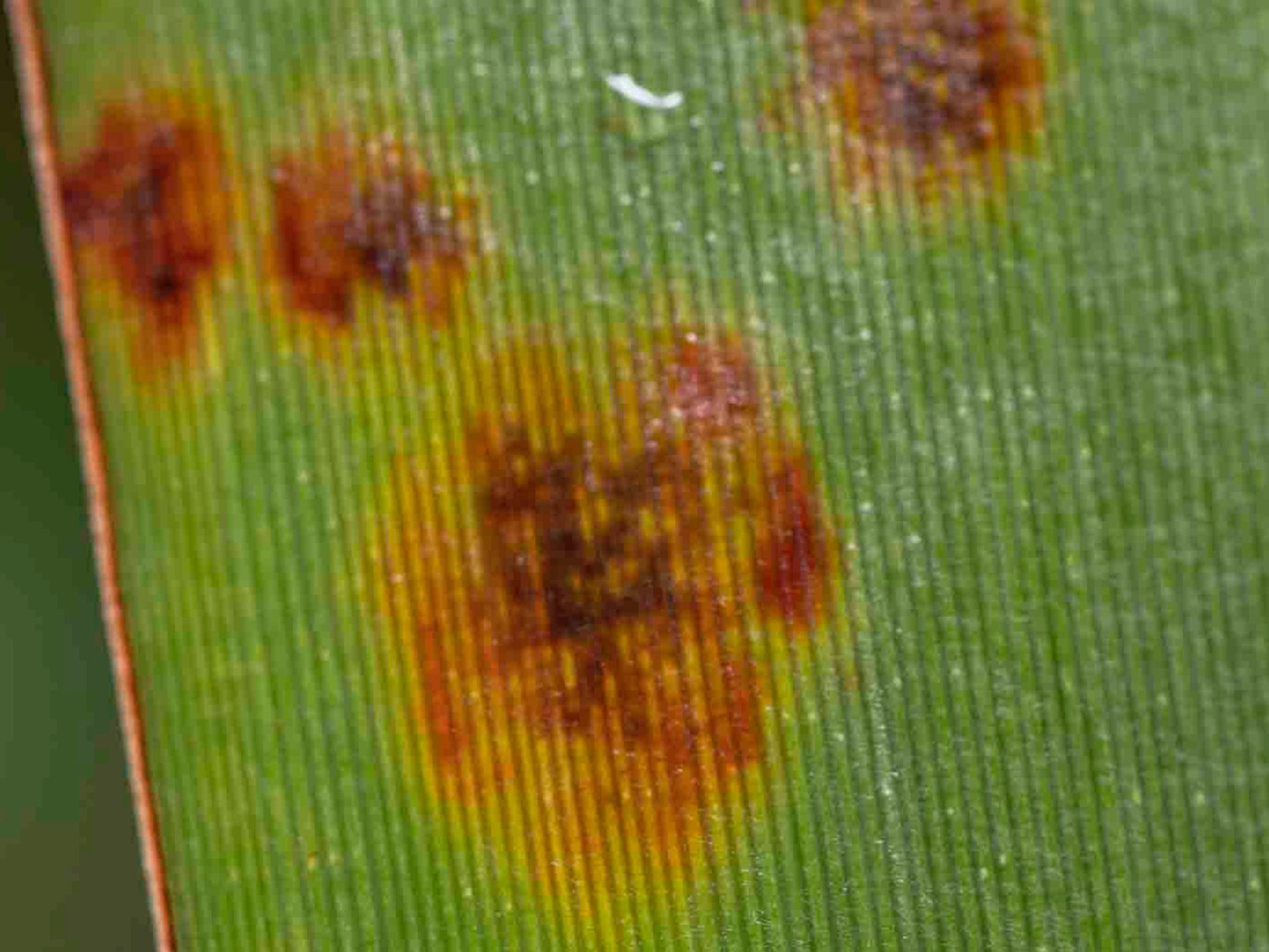

Look for the telltale fungus infection spots on living mahoe, karo or karamu leaves where sap-sucking psyllid insects have injected spores from these parasitic fungi into their leaves. The plants strategy is to grow new leaves faster than the old ones can be destroyed by disease. Not all fungi are parasites though, many are saprophytes – living off already dead plant material, recycling it. A few are both – killing the host parasitically and then feeding off the corpse saprophytically!

Another vital role of many fungi is to help tree roots absorb water and minerals from the soil in exchange for sugars and proteins from the roots. The fungal threads do this by penetrating right through the root cell walls (but not entering the cell cytoplasm). This close partnership is known as a mycorrhizal association, a relationship that has long been known to exist between fungi and conifers as well as orchids. Today it is thought that nearly all plants and trees have their own specific fungus partners performing this service. The fungi not only increase the surface area of the roots for enhanced nutrient absorption, but also exude chelating (or “capturing”) chemicals which bind onto scarce soil nutrients making them more available to the plants.

Mycorrhizae are especially beneficial for the plant partner in nutrient-poor soils, such as those found near the top of the Wattle Track.

Other recent studies have shown that these fungi target specific parts of different root systems for maximum gain, “trading” less abundant soil minerals for the best quality nutrients from the plants. In addition, several types of specific “helper” bacteria work closely with the fungi to enhance their ability to take up soil nutrients for the plants.

Sugars have also been shown to move between different species of tree via mycorrhizal network, promoting the succession of tree species as ecosystems change over time. For a new seedling in the forest to thrive, it is important for them to acquire their own mycorrhizal partner as quickly as they can.

When both parties benefit from a relationship is called mutualistic. Fossil evidence and DNA sequence analysis suggest that this mutualism appeared 400 – 600Mya, when the first plants were colonising land.

Fungi also act as a food supply, forming a vital link in the food web of the forest. A wide range of invertebrates such as springtails, mites and fly larvae graze on them, and they in turn feed the birdlife on Tiritiri Matangi Island. Without the Fungi life would be exceedingly dull for us humans – but imagine a forest where no dead trees are broken down and recycled!