The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy

The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy

Author: Emma GrayDate: 28th September 2023

Header image: John Sibley

The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy. I always think I’m ready with my island feet until I fall over for the first time and bring myself back down to earth. The hihi team is very small at the moment as we perform our pre-breeding season tasks including the survey, sugar feeding handover from the rangers, and a lot of cleaning.

The pre-breeding survey entails 40 hours spent walking all the tracks and bush patches on the island, including spending time at the sugar feeders in both the morning and afternoon to see which adults are still alive and which juveniles from the previous season have made it through their first winter. Hihi juveniles have a 40% survival rate through the first winter, which we know due to our annual mark-recapture surveys. Mark recapture in the case of the hihi means banding all individuals with a unique band combination, most likely banded as chicks in the nest, and recording the individuals, their sex (in case we got it wrong) and their location/potential territory for the upcoming season.

The sugar water consumption is highest on Tiritiri Matangi Island during the winter (thank you to the island rangers who keep these hungry birds fed daily) unlike other hihi sites. This is due to the lack of natural food available over winter, while the fruits, flowers, and invertebrates that hihi feed on are numerous in spring/summer.

Once the 40 hours of the survey are complete, we’ve then got the task of cleaning out 200+ nestboxes so they are spick and span after being used as roosts over winter. Unless they are already occupied by other wildlife and the beginnings of the stick base for hihi nests.

The hihi have been surprising us this year by laying eggs almost a whole month early. They are keeping us on our toes and making the most of the abundant natural food available. Currently, the hihi aren’t spending much time drinking the provided sugar water at the hihi feeders and instead determining social hierarchy and territories. The male hihi are displaying in their territories, while the females are either getting ready to lay eggs or still picking their partner for the season.

The females usually build their nests slowly during late September and early October with the first eggs typically laid around mid-late October. Our first-year females often don’t attempt their first nests until December! Looks like we have an interesting season ahead.

From planting some of the first trees to using them for shade from the sun

From planting some of the first trees to using them for shade from the sun

Authors: Students from St Cuthbert's Year 7Date: Thursday 21st September 2023

Header image credit: Martin Sanders

“Today St Cuthberts Year 7 visited Tiritiri Matangi. When we arrived, we admired the crystal clear water and the beautiful greenery that surrounded the island. As we were guided around the Island by the kind guides, we experienced all the beautiful songs of the birds. We learnt so much about all the different kinds and species of birds, trees, plants and so

much about the history of the Island. It was very inspiring to know that our school was part of restoring this beautiful Island. We had so much fun learning about all the cool facts our guide taught us. Our favourite fact was that some wētās, if they land on your hand, it feels the same as when your fingernails dig into your palm.

Thank you so much for having us, we loved the experience.”

Chloe and Lucy

“Our trip to Tiritiri Matangi was spectacular! We learnt various facts about the wildlife there, all sorts of birds and most importantly we learnt about the inspiring history of the Island. Many people used to come to Tiritiri Matangi to plant trees and help make it the beautiful Island you see today. If you do something good, people will remember you! The Island of Tiritiri Matangi is invasive pest-free and definitely worth visiting. It is so interesting and such a beautiful place to visit.”

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Sasha and Lila

“Our school trip began with fog so thick it looked like someone had placed a dolly blanket over Auckland. On the ferry, we could only see the expanse of water and fog and smell the salty air. When we got to Tiritiri Matangi the first thing we noticed was the perfectly clear water that glimmered in the sunlight. When we stepped onto the dock a stingray caught our eyes, it was named ‘smoky’ by Pippa, a girl in our class.

Along our trail, we saw an absence amount of birds. A ruru, a kererū, tūī, tīeke and a kōkako; one of the rarest birds to see. We also saw three wētāpunga, the heaviest insects in the world, and one female tree wētā.

At the top, there was a beautiful view of the forest that was planted by many hardworking volunteers. Our trip was amazing because of our volunteer guides, we will be coming back soon.”

Chloe and Zytak

“Going to Tiritiri Matangi was truly an inspiring experience. We got to explore and learn about all the different types of beautiful birds, insects and plants. We felt proud knowing that in the past St Cuthbert’s planted many trees. Our amazing guide, Neal led us along the way and showed us all the living things around us. We experienced things that we barely get to appreciate and see in Auckland. On the boat ride there, we got to spot the jellyfish. As we were walking around the Island pathways, we could hear all the birds tweeting amongst each other. We also got to admire the breathtaking view and look at the different equipment that was used ever since 1987.

Our trip to Tiritiri Matangi was unforgettable and we want to thank all the teachers and staff at the Island who dedicated their time to make this an unforgettable memory.

Thank you so much this trip!!!”

Mahnoor and Beau-Ruby

“Our visit to Tiritiri Matangi was eye-opening and we will definitely remember it. We heard and experienced the unique wildlife of the Island. We found this trip to be inspiring and we’ve made so many special memories. It was really amazing to be in the same place that St Cuthbert’s old girls had been and had planted trees in many years ago. We hope that we can make such an impact on our planet as they have.

The St Cuthbert’s students would like to recognise and acknowledge all the staff and volunteers at Tiritiri Matangi who went out of their way to show us around and make this experience one to remember”

Ainslie and Kalila

Eight long needles of light

Eight long needles of light

Sourced from Tiritiri Matangi, A Model of Conservation, Anne RimmerDate: 17 September 2023

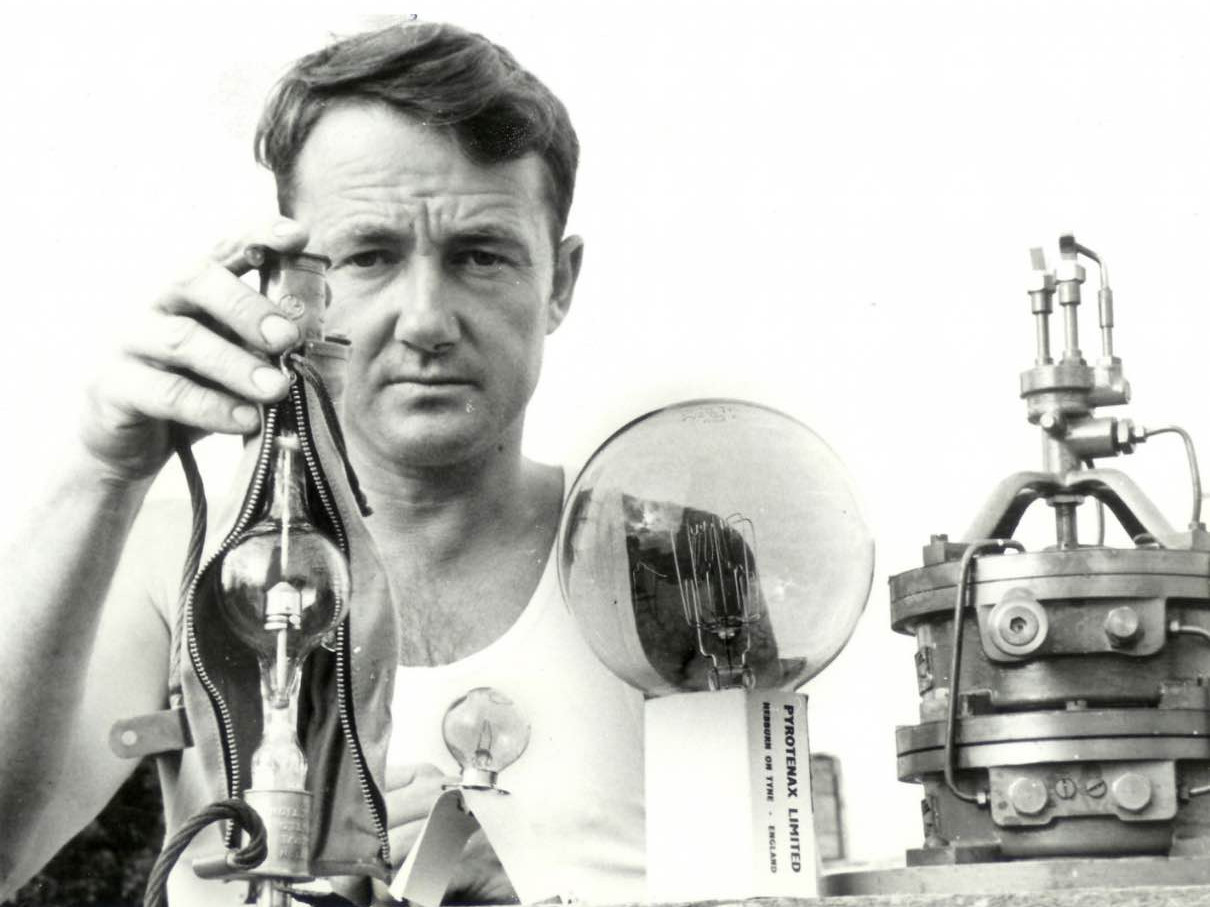

Header image: 'Eight long needles of light': the David Marine Light, 1965

Credit: Peter Taylor

Did you know that the Tiritiri Matangi lighthouse is a Category 1 historic place? It was actually the first lighthouse to be established on the approach to Auckland in the Waitematā Harbour. Interestingly, when it was built, there were only two other lighthouses in the entire country, Pencarrow (1859) and Boulder Bank (1862). Today it is New Zealand’s oldest working lighthouse.

The lighthouse in New Zealand was a remarkable feat of engineering. It was designed by McLean and Stilman Civil Engineers in London, and constructed by Simpson and Company. The prefabricated parts were shipped all the way from London to New Zealand, where they were put together. The end result was a stunning structure that served as a beacon of light for ships navigating the nearby waters.

It’s impressive to think that the original light lasted a whole 60 years before being replaced with the 11 million candlepower xenon lamp in 1965. There were murmurs among Aucklanders that the Tiritiri Matangi light was inadequate, likened to “just a glimmer, like someone standing up there with a torch.” Fortunately, Sir Ernest Davis, a former mayor of Auckland, prominent businessman, and avid yachtsman, generously donated £80,000 to give Auckland the light it deserved. This donation was widely publicised, and the new light, featuring a small but powerful 1800-watt xenon bulb was given the nickname ‘the Davis light’. The eight beams flashed every 15 seconds and was known to be the most powerful light in any lighthouse in the southern hemisphere. To power the Davis light, the island was connected to the national grid in 1967 via an underwater power cable. Laying the cable had required meticulous planning.

Principal Keeper Peter Taylor said “As a loom in the sky, it has been reported by ships 50 miles away, and some North Shore residents go to sleep watching it sweeping past their bedroom walls.’ It could even be seen by the Apollo astronauts in space.”

Ray Walter, the last lighthouse keeper and the first ranger of Tiritiri Matangi Island, has spent many hours, love and care restoring and preserving the Davis light and many other maritime items. These are on show in the Tiritiri Matangi Lighthouse Museum.

Tracking tunnels on Tiritiri Matangi

Tracking tunnels on Tiritiri Matangi

Author: Neil DaviesDate: 15th September 2023

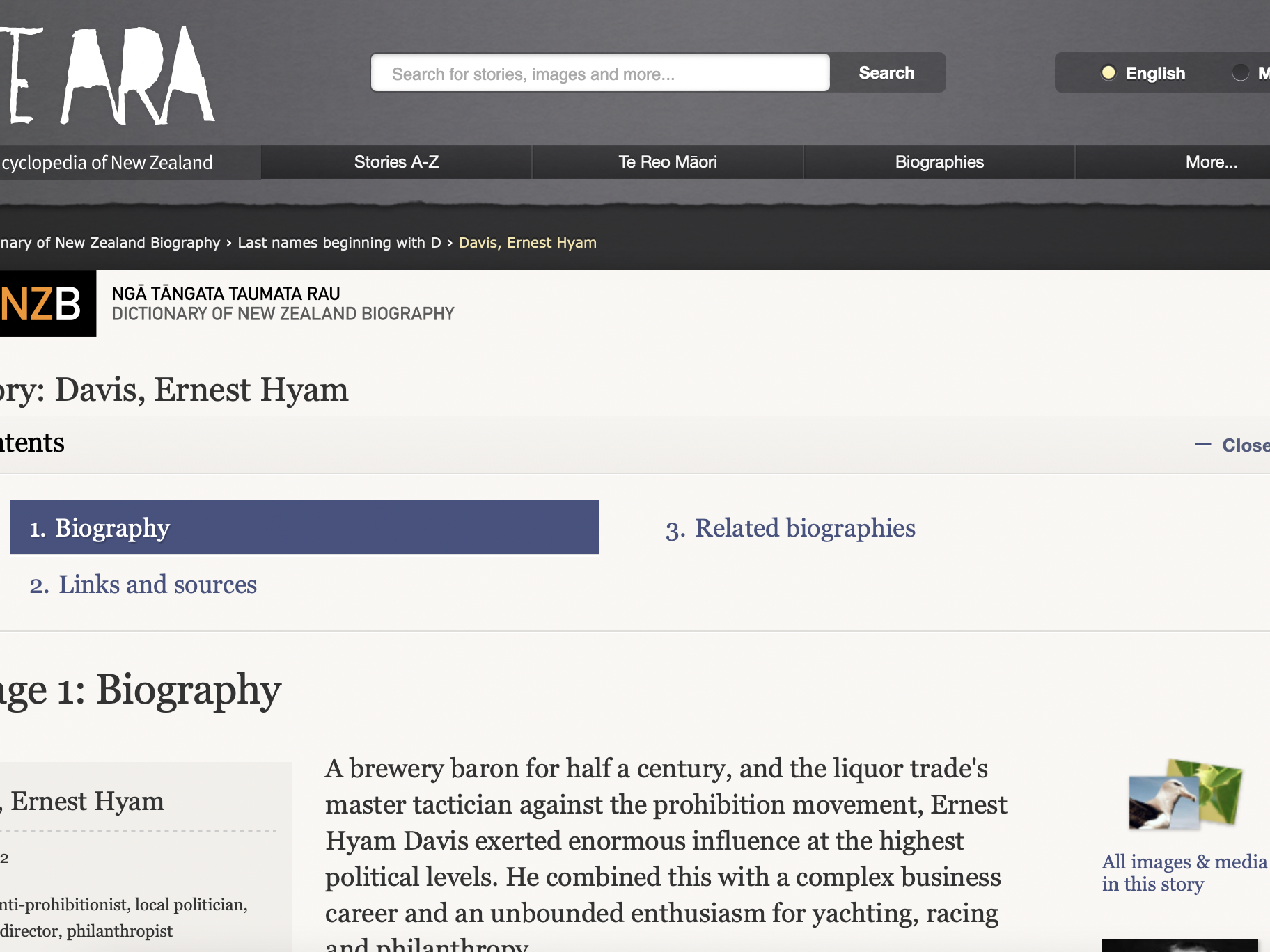

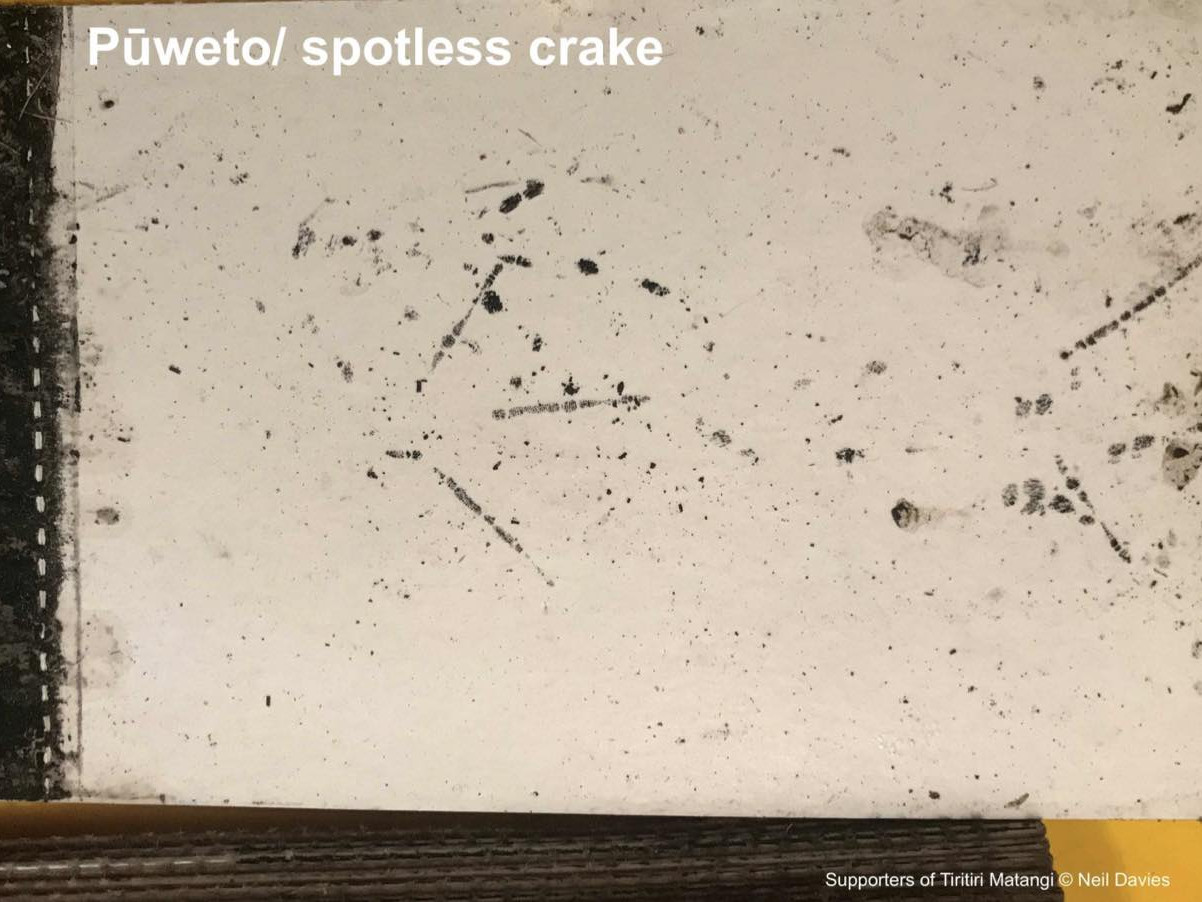

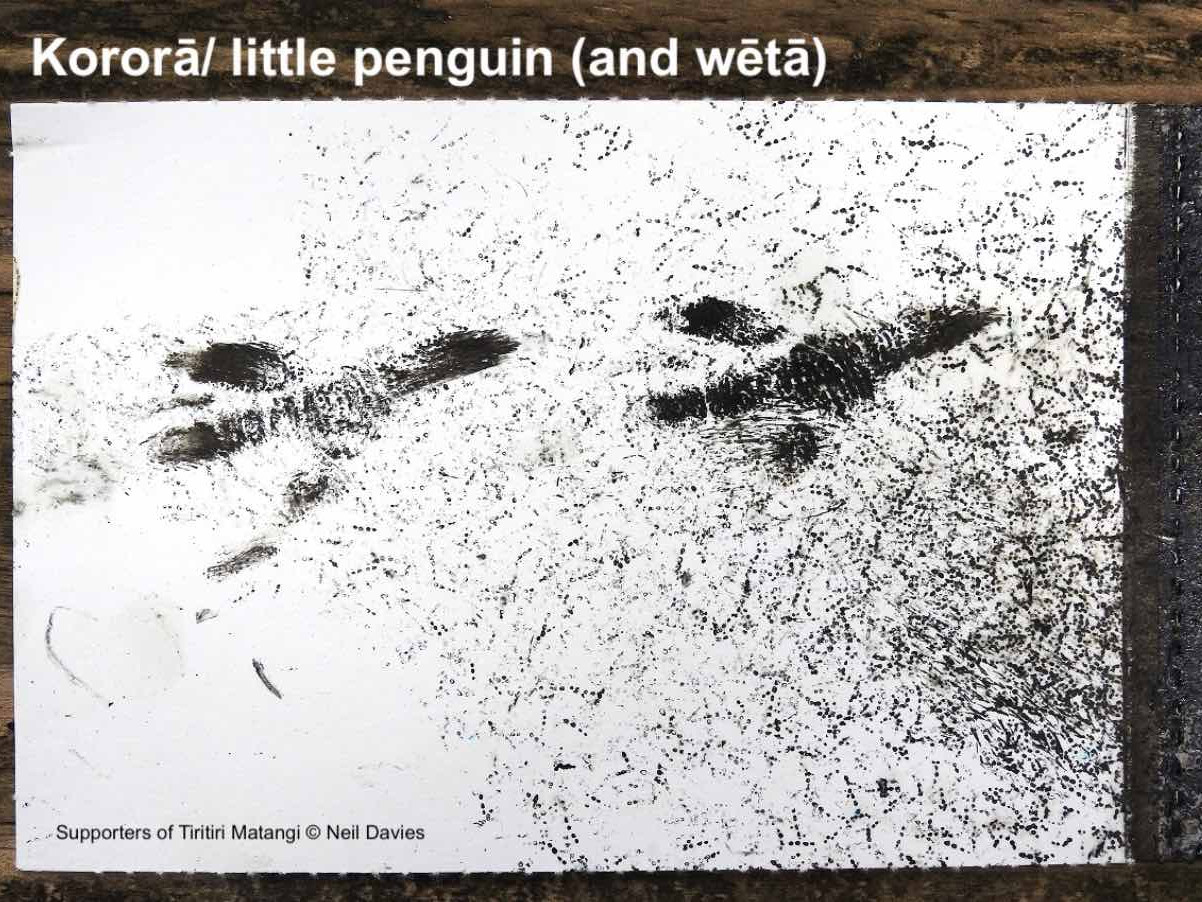

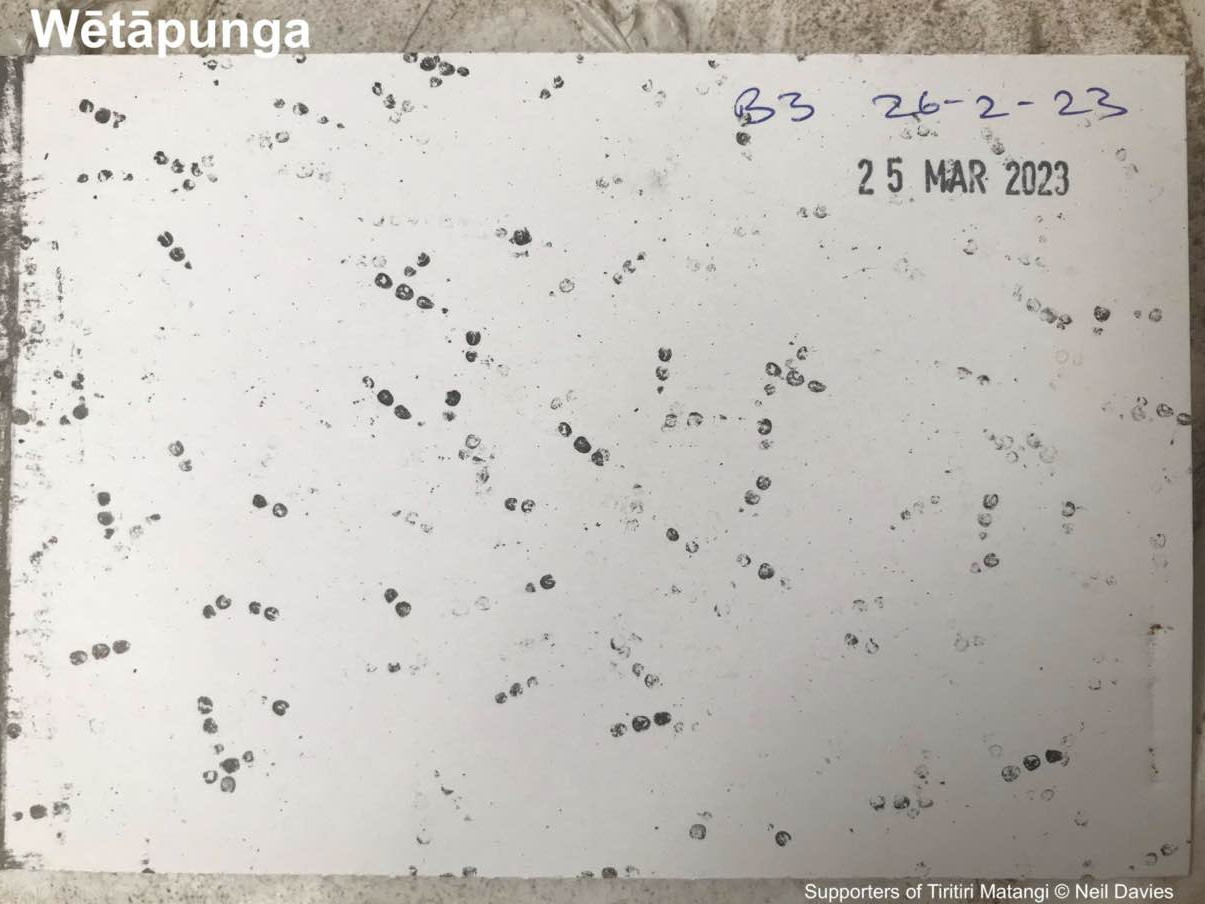

Tracking tunnels on Tiritiri Matangi are used as a biosecurity monitoring tool for detecting the presence of unwanted organisms such as rats or mice. They can also build up a picture of what animals are present in a certain area. The cards inside the tunnels are inked in the middle and have peanut butter as a lure. Animals that are attracted by the smell of peanut butter enter the tunnel and walk across the ink to reach the peanut butter. When they exit the tunnel they leave footprints (and sometimes marks from the body or tail).

In the past, the cards were left out for a month but now they are put out one weekend and taken in the following weekend. Tracking cards are also being used to monitor reptiles on the island. It was through a tracking tunnel that a Norway rat was detected on the island in January 2018 with its prints appearing on the tracking card. It is the only rat incursion that we are aware of since kiore (Polynesian rats) were eradicated in 1992-3. Fortunately, it was caught within two weeks, before it was able to cause too much damage.

More typically though, footprints of skinks, geckos, wētā, wētāpunga, tuatara and birds eg. Pūweto/ spotless

crake and, occasionally, kororā/ Little penguin, show up on the cards.

How a shortage of rakes led to the creation of an extraordinary environmental legacy

How a shortage of rakes led to the creation of an extraordinary environmental legacy

Author: Jim Eagles, taken from the Dawn Chorus Bulletin 113Date: May 2018

Jim Battersby was first and foremost a Presbyterian minister, having been ordained in 1953 and retired in 1987. In an article written for a church magazine in 2006 he recalled that, ‘Like many of my generation of students, I felt the call to ministry early after leaving secondary school, and so ministry became my whole career. I served 22 years in three parishes, and about 13 years in a hospital chaplaincy.’

Unsurprisingly, when he retired from the ministry, it left a big gap in his life. And, as it happens, about this time the island of Tiritiri Matangi had stopped being farmed and, thanks to the efforts of people like John Craig and Neil Mitchell of Auckland University, was slowly being re-afforested under the supervision of former lighthouse keepers Ray and Barbara Walter. And the Battersbys started to get involved.

Asked at one of his talks how he came to get involved, Jim said he thought the fact that he and his wife Barbie had island blood, his people coming from the Chathams and hers from the Isle of Man, made them pre-disposed to like islands. But the immediate reason was that when he was chaplain at Greenlane Hospital ‘a friend who also worked there came to visit us and said she’d been planting pohutukawa on this island. We thought that sounded interesting and she said, “Well, if you want to go, get in touch with Barbara Walter.”

‘So we got in touch and asked Barbara if we could visit and join the planters and she arranged for the Torbay Garden Society, which we belonged to, to come over planting. There were all sorts of organisations that came over in those days, schools and churches and service organisations, periodic detention people, tramping clubs … all sorts . . . they were wonderful.’

Barbara Walter also remembers those days well. ‘As the planting programme got going we had volunteers coming all the time. Groups like 60s Up used to ring up and say they’d like to help and I used to organise them. They’d come for day trips to do planting mostly or sometimes to stay over to work in the nursery. I particularly remember Jim bringing a church group which did a lot of planting, including some pūriri trees on the eastern side, which are pretty huge now.’

Then in 1988, the year after he retired, Jim and Barbie went to Tiritiri to spend a week in the nursery which was producing the seedlings to be planted. In one of his talks on SoTM’s history Jim recalled, ‘I was given a job of weeding the polythene that was in the setting-out bay. And I said to Ray, “Why do we have to weed this, can’t we get some new polythene?” And he said, “We’ve got no money.”

‘So I thought and thought, and while I was sitting on the seat that’s still there on the Wattle Track, the idea came to me: if we could get a hundred people from those that are doing the work here now to put in $10 each we’d have enough for the polythene.’

Ray and Barbara Walter’s recollection is that what started things off was a shortage of rakes. ‘I asked him to tidy up the plant holding area and he’d only been working for about 10 minutes when he came back and said, “Can I have a rake,” remembers Ray. ‘And I had to tell him, “Sorry, you can’t, someone else is using it.” And he said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “We’ve only got one.” And it was the same with everything else in those days. We didn’t have much. So he said, “This isn’t right. Something needs to be done about this.” And off he went.’

Either way, Jim bounced his idea of forming a group to raise money for the Island off his wife and the Walters, and they responded enthusiastically, so he decided to go ahead. ‘We met first at my place. About six of us,’ he used to say in his talks, before producing a few handwritten pages with a flourish and adding, ‘and I’ve got here the minutes of that first meeting.’

Next he asked Barbara Walter to give him 25 names of people who regularly came to Tiritiri ‘and then we called a meeting in St Matthew’s Church in the City, because it was so central and somebody belonged there, and that’s where we moved the Supporters of Tiritiri be formed on August 24th 1988. We got going with, I think, about 30 members, who all paid our first $20 donation for the organization that was founded. And we decided we should become an incorporated society and that meant we couldn’t have donations, we had to have actual subscriptions.’

One of the people at that meeting was Mel Galbraith, who described in his eulogy at Jim’s funeral how he listened with fascination as ‘Jim introduced the concept of a supporters group for Tiritiri Matangi. Like Jim and the others gathered at the meeting, the Island had become an integral part of my life, and thus we all had a vested interest in the welfare of the project. Jim delivered a very persuasive argument for the formation of the support group, and the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi was launched with unanimous backing. Jim was, naturally, elected chairperson, and I volunteered to be secretary.’

It has to be said that not everyone involved with Tiritiri was very impressed with the formation of this organisation. In fact probably Jim’s favourite story from this time is of the fledgling SoTM going to meet the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park Board, which at that time was in charge of islands like Tiritiri, ‘and we told them what we were trying to do. We heard afterwards that they thought we were an enthusiastic band of hopefuls that would probably fade out in a year. In a year’s time Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi were going on from strength to strength and the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park Board had ceased to be, taken over by DOC.’

Despite the pessimistic official response, things were starting to move. Jim described how, ‘At the first committee meeting my wife Barbie was elected editor of the newsletter and the first one was sent out,’ and for his talks he always produced a copy of it. ‘Another of the early things we did was to say we need a logo and somebody said, “I know somebody who designs logos.” So I said, “Well go ahead and get him to do it.” So after two or three attempts they designed the logo with the saddleback as the feature of it and, having said “thank you very much,” we got a bill for $150 and we hardly had $150 in the coffers.’

But the main thrust of the new organisation was to support the work already underway to raise trees and then to plant the seedlings out. So more boat trips were organized to take volunteers to the Island to collect and raise seed, then plant the seedlings and, of course, the organization bought equipment like rakes. Ray Walter says it naturally took time for ‘things to get wound up. But after a while money started to trickle in for all sorts of things, which relieved us from all the problems DOC was having with its budgets. Our founding money was from the World Wildlife Fund, who got funding from about four major sponsors. But when that ran out it all reverted back to DOC and their budget was very tight.

When DOC was formed they ended up with a whole lot of staff from, I think, four departments, many of whom they had to pay off and make redundant. So right from the very beginning DOC was hamstrung and money was just not available. Nothing much has changed there. But we had the Tiritiri Supporters which was able to come up with a little money to buy things.’ Jim was particularly proud when SoTM was able to buy some proper planter spades for volunteers. ‘In the early days we brought our own spades to do our planting with us. Then gradually the committee bought long drain shovels which were excellent for digging holes and we would dig the holes and carefully pull back the grass, put in some fertilizer and stamp the things in.’

That technique was developed very early on, he liked to explain, because on the first day of the big pohutukawa planting ‘1200 pohutukawa seedlings were planted by just popping them in and pulling the grass away to let the light in. ‘And the next morning 700 of the trees were lying on the ground because the curious pukeko had said, hello, these weren’t here yesterday, we better have a look and see what they are. So we learned that whenever the planting was done the tree was stamped in and the grass was pulled up and the little . . . couldn’t see our trees.’

Another thing Jim used to recall with particular pleasure was the times he and Barbie were able to stay for a week in the old bach ‘and we went seed-gathering, all sorts of seeds, particularly the coprosmas and also the ti kouka, the cabbage tree, and various other things. We gathered the seeds and Ray would put them in a bucket for three days until the outer flesh rotted away and then the seeds were taken out and dried and eventually planted out in trays in the glass house.’

Then he discovered that Ray had developed an even more efficient method of getting seeds. ‘One day I rang Ray saying, “I need to talk,” and Barbara said, “He is out gathering pigeon droppings.” I said, “What on earth is he gathering pigeon droppings for?” She said, “Well, the pigeons eat the puriri seeds and then they pass them through their bodies and Ray gathers them up and plants them as puriri trees.” As easy as that.’ Nevertheless, working on Tiritiri in summer could be hot work and one scorching February day when he and Barbie were out gathering seed ‘we thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we had a motorbike. So we came back and said to Ray, “Would you like a motorbike?” And he replied, “I’d rather have a quad bike”.’

That conversation turned out to be rather significant because it launched SoTM into its hugely successful programme of getting grants from various funding bodies to buy equipment for the Island. The chosen vehicle and trailer were bought for a good price through somebody who knew somebody but, as Jim recalled, ‘they’re gonna cost $9000 and where do we get $9000 from? And somebody said, “Why don’t you try the Lotteries Board.” But I was a Presbyterian Minister! Lottery? But the majority, of course, prevailed so we applied to the Lotteries Board and to our surprise we got the $9,000 we had applied for.’

Ray says the arrival of that quad bike was ‘the single thing that made the biggest difference in those early days because it opened up the whole of the Island to the rangers and made it so much easier to get around and do things.’ Another key difference SoTM made was with the shop, which Barbara had started in the teeth of opposition from DOC. ‘They told her, “We don’t have shops in DOC any more because they lose money”,’ recalls Ray. ‘But eventually, they gave her $400 which she used to buy t-shirts. ‘She rang up on Monday and asked for more money because she’d already sold the lot. And they said, “Oh, no, that $400 was your annual budget.” So she said, “Okay, I’ll spend my own money to buy stock and the proceeds can come back to the Island.” And later on, of course, Tiritiri Supporters provided the money to buy stock. ‘That’s why, when concessions came up on Tiritiri, it was the Supporters who got them because they were already providing the funding. And that’s why all that income from the shop and guiding comes back to the Island instead of going somewhere else.’

But, although SoTM was thriving, its membership growing, donations and grants starting to come in, celebrities like Prince Philip and David Attenborough coming to call and the work of restoring the Island progressing well, Jim himself was going through a difficult period. After three years as chair, he stepped down; he and Barbara had sickness problems, sold their home, which was proving too big for them to look after, and moved into the Hillsborough Heights Retirement Village in Mt Roskill. Then they took a three-month trip overseas ‘during which Barbie became ill, tour plans had to be changed considerably. Barbie died five days after we returned and my life exploded.’ Barbara Walter remembers that during this difficult time Jim kept coming to the Island to help ‘but he seemed a wee bit lonely, and we always needed more guides, so I asked him to become a guide. As a guide he got to mix with more of the Supporters and more of the guides and he became more well known. He was a wonderful guide because he had so much history to share. A lot of the later guides didn’t know how it all happened in the beginning and he was always there, especially on our guides’ days out, with advice or to answer questions.’

That involvement naturally began to slow as he got older but Jim continued his involvement with the Supporters, giving his last historical talk to members – on which this article is partly based – in 2016 and speaking at last year’s AGM. Mel Galbraith commented in his eulogy, ‘I believe the SoTM committee, and indeed the Supporters collective in general, became Jim’s flock. Under Jim’s pastoral care, we were managed efficiently, but with a delightful sense of fellowship. Our early committee meetings were held at the Battersby residence and after each meeting it was always compulsory to take home some homegrown produce – usually a bag of grapefruit. Jim hated to see surplus fruit going to waste!

‘Our society does not have the provision for a Patron, but we certainly had one anyway. After Jim had left the committee, he continued to be a participant in the project, and a staunch supporter of the society. His encouragement and, most importantly, his carefully measured guidance, was a regular general business item at our AGMs.

‘Any of us who had become entrenched in the Tiritiri Matangi project could have initiated a supporters group for the Island. But we didn’t. Jim had the vision, and applied the people-management skills associated with his ministry to effect. He mobilised us, he encouraged us, he cared for us. ‘SoTM is an example of the power of citizen participation in conservation, with its achievements recognized both nationally and internationally. The SoTM is Jim and Barbara Battersby’s legacy to us.’

Two men and a baby

Two men and a baby

Author: Story shared by Vic Hunter and text taken from SoTM Dawn Chorus Bulletin No.10 May 1992Date: August 2023

In January 1992, Stormy and Mr. Blue, two male takahē, successfully raised a chick. It was not unusual for male takahē to share in nest building and incubation, so it was no surprise when they showed a desire to incubate a ‘dummy egg’. Their readiness to incubate prompted DOC to find a real egg for them. A ‘spare egg’ became available when a pair on Maud Island in the Marlborough Sounds produced a clutch of two eggs. The DOC staff ferried the takahē egg by boat off Maud Island while Ray Walter was flying to Blenheim by chartered aircraft. The incubator was exchanged in a brief encounter on the tarmac at Blenheim airport, and the precious cargo was soon on its way north to another airport. Tony Monk was waiting at Ardmore with his helicopter to complete the final leg of the journey, and by mid-afternoon, the egg was safely transplanted snugly under its foster parents. It was a successful operation.

It’s amazing to think that Matangi is the first takehē to hatch in this part of the country in centuries! Four days after the egg was transplanted, Matangi emerged from its shell. Ray, Barbara Walter and Vic Hunter were so diligent in caring for the chick that it even survived a potentially deadly encounter with heavy rain when it was just three days old. It’s wonderful to see such dedication towards preserving endangered species like the takehē.

Vic Hunter shares…

It was just after the Christmas period in 1992 and there was a terrible cyclone. There was Ray, Barbara and me on the island. Before Christmas Ray had noticed Stormy and Mr. Blue making nests by the Implement Shed and got in touch with DOC. They sourced an egg and the two takahē took it in turns to sit on the egg. It wasnt long until the egg hatched.

It was a wild stormy night when the cyclone hit. The rain was pouring down, and it was very cold. That’s when we saw the chick struggling to survive in a puddle. We knew we had to help. We quickly took it to the old tin garage, where the Ray and Barbara Walter Visitor Centre is now situated. The chick’s wings were splayed out, and it was lying face down. It looked so helpless. Barbara went to the house to get a hot water bottle and a towel. She placed the chick on the towel over the bottle. Then she took out her hair dryer and started to dry the chick’s feathers. It didn’t take long before the chick started to look more lively and fluffed up its feathers. We were all so relieved to see it lift its head and know that it was going to be okay.

As Mr. Blue walked into the garage, Stormy seemed a bit more reserved. However, Mr. Blue was always a constant presence. He perched himself on the chick and began to brood. The rain continued to pour outside, so Ray made the decision to keep the chick in the safety of the garage.

We went and found some grass to make a nest for the chick, but all the grass was very wet. So, we used the hair dryer to dry the grass. Ray made a 6-inch quad nest using some boards. We put the grass inside it, and Mr. Blue got on top to sort out the nest into layers, tossing out bits here and there. Since Mr. Blue had nothing to feed the chick, we went and found insects, worms, and snails. Mr. Blue started to feed the chick in the safety of the garage during the rainy weather.

It was early evening, we released we had to keep the chick in the garage because it was still too wet and cold outside. Since there were a lot of kiore in the garage, we had to be careful and make sure that the chick was safe. We decided to take turns sitting with the chick and shining a torch whenever we heard a noise. This seemed to work well, as the kiore were scared away by the light. We spent about an hour or two each, taking shifts and keeping watch over the chick. It was worth it to make sure that the chick was safe and secure.

The chick and Mr. Blue were sound asleep. Every now and again, the chick would let out a ‘cheep cheep’ and Mr. Blue would respond with a calming thumping noise, which helped the chick to go back to sleep. This happened a few times throughout the night, and it seemed like the chick felt safe and secure in its new surroundings because it would go back to sleep.

Ray started to build a shelter in next morning for the chick and Mr. Blue using 8 by 4s. He set it up in the long grass by the Implement Shed, with walls and a step that was steep enough to prevent the chick from escaping but not too steep for Mr. Blue and Stormy to enter and get out of. We moved the nest that had been made the night before to the shelter, and I carefully carried the fluffy and light chick in his cupped hands to keep it safe. The chick felt so fluffy and was so light to carry.

After the cyclone subsided, the weather cleared up and I noticed Mr. Blue wandering in the long grass, not too far from the shelter. Suddenly, a harrier flew overhead, and Mr. Blue immediately bolted towards the shelter and perched on top of the chick. It’s heartening to witness Mr. Blue’s protective instinct towards the chick.

Left video recorded by the Tiritiri Matangi DOC rangers

Right video recorded by Neil Davies

Adventures in "Deep Time"

Adventures in "Deep Time"

The First "Seed Plants" (Spermataphytes)

Author: John Sibley

Image credits: John Sibley

The ferns always had a major drawback when it came to occupying the dry land, and although their dominant sporophytes have well-developed internal tubes in their stems to carry water up to their fronds, they have a reproductive “Achilles heel” in that they possess mobile sperms with lashing tails which must swim in surface water films in order to reach female fern egg cells in order to fertilise them.

The seed plants (Spermatophytes) overcame this limitation by producing male gametes (“sex cells”) in the form of dry pollen, often carried on the wind or transported stuck to insects bodies. Apart from other fundamental structural differences seeds are generally much larger than fern spores, and contain food reserves for the growth of the young embryo plant giving them a significant advantage. This subject would demand an entire episode to explore fully! These seed design breakthroughs would see the seed plants begin to replace the spore-bearing ferns as dominant players in the Gondwanan forests of the late Permian period 250 million years ago.

The very first seed plants may have appeared as early as the Devonian 350 million years ago, starting with the so-called “seed ferns” but it wasn’t until the late Permian/ early Triassic periods 250 million years ago that the seed plants finally came into their own with forests dominated by the now extinct Glossopteris trees towards the end of the Permian.

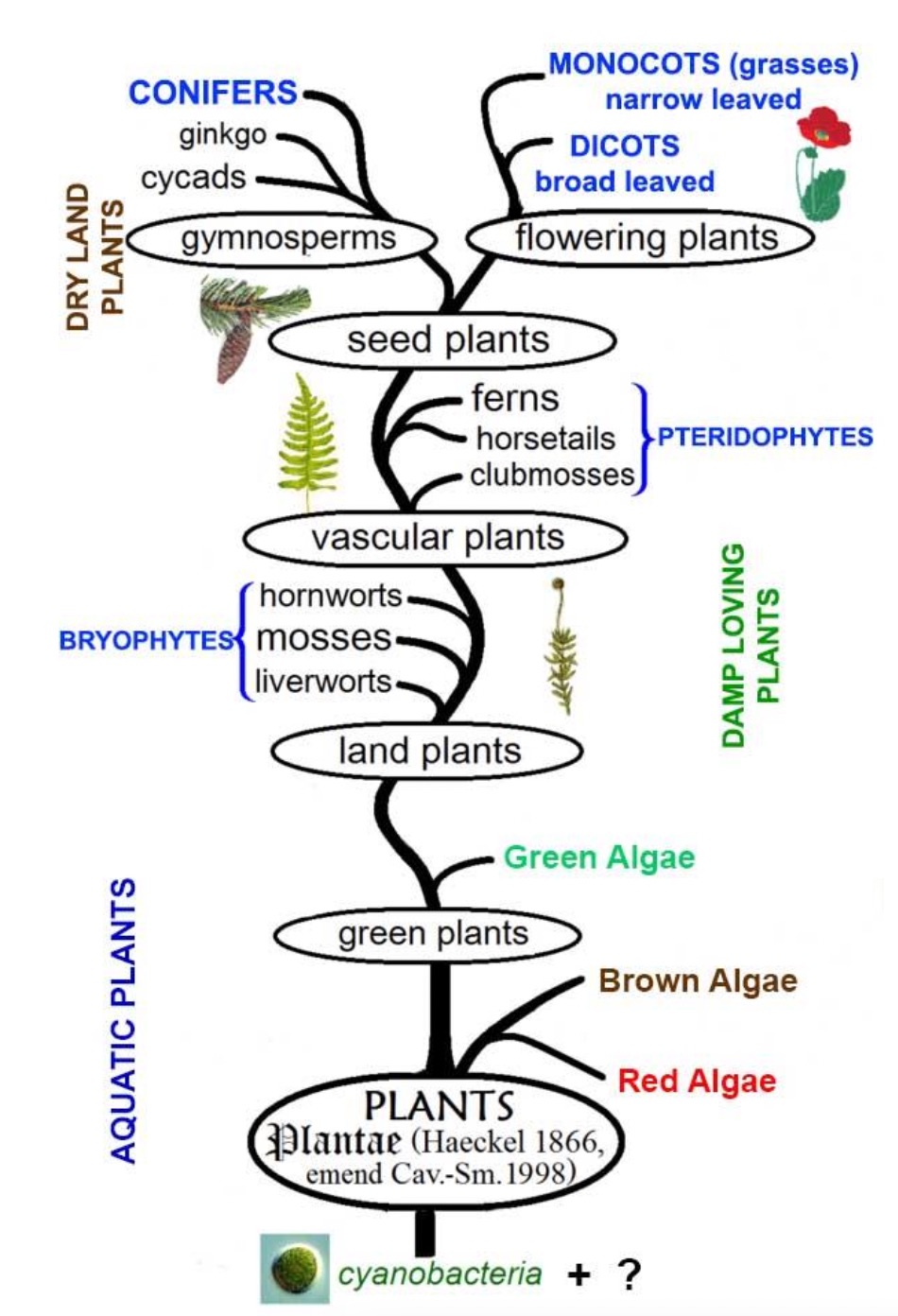

Todays seed plants are divided into 2 main groups:

Gymnosperms = “Naked seeded” Pinophyte Conifers with seeds exposed in cones, comprising the Pinophytes (Pines), Cycads, Ginkgos and Gnetophytes. These last three are not native to NZ but Cycads and Ginkgos are often grown in NZ gardens as introduced specimen plants. The second group of seed plants are the Angiosperms = Flowering plants with seeds hidden and enclosed within a fruit. This group includes the grasses. We will look at the Angiosperms in the next issue.

We will look at the Gymnosperm pines or Pinophytes belonging to the Family Podocarpaceae (Podocarps) found on Tiritiri Matangi that originated from the ancient continent of Gondwana before New Zealand broke away some 80 million years ago.

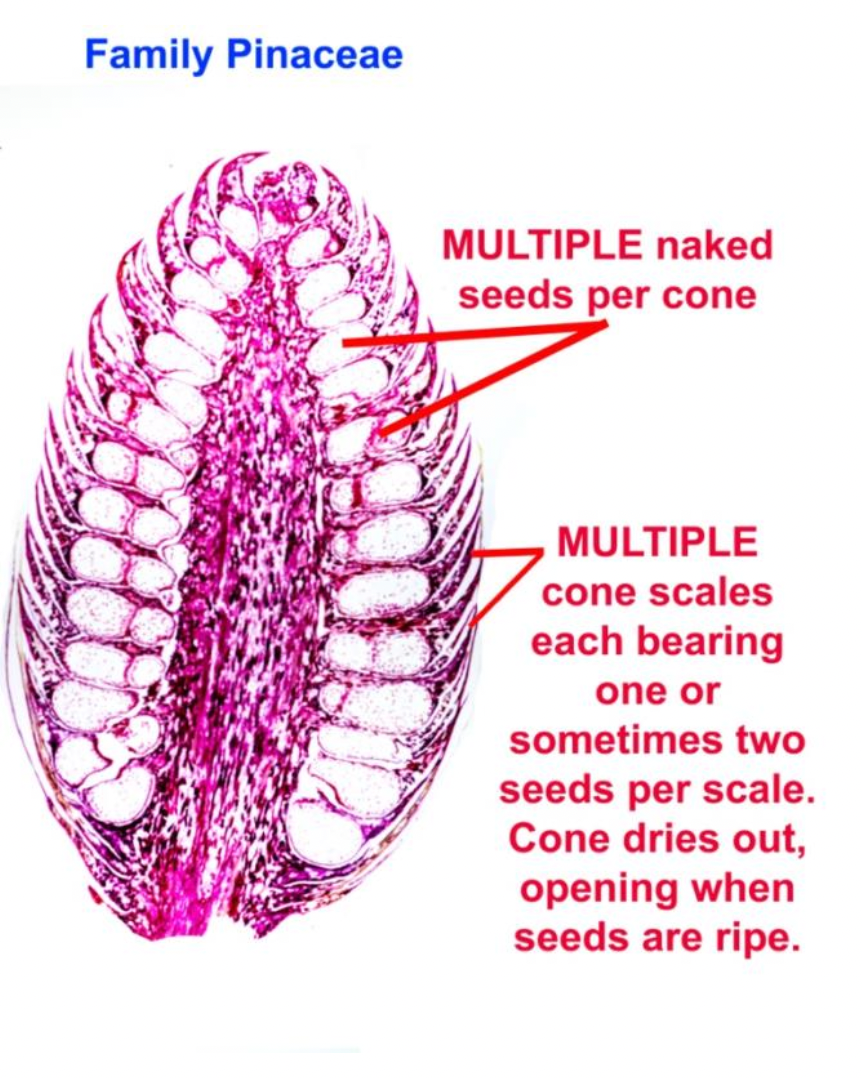

Those with Northern Hemisphere links will immediately associate the term “pine tree” with long thin needles and large fist sized pine cones – eg Pinus patula the Mexican weeping pine (see right), or Pinus radiata, the Monterrey Pine grown extensively in NZ for its timber and originating from California.

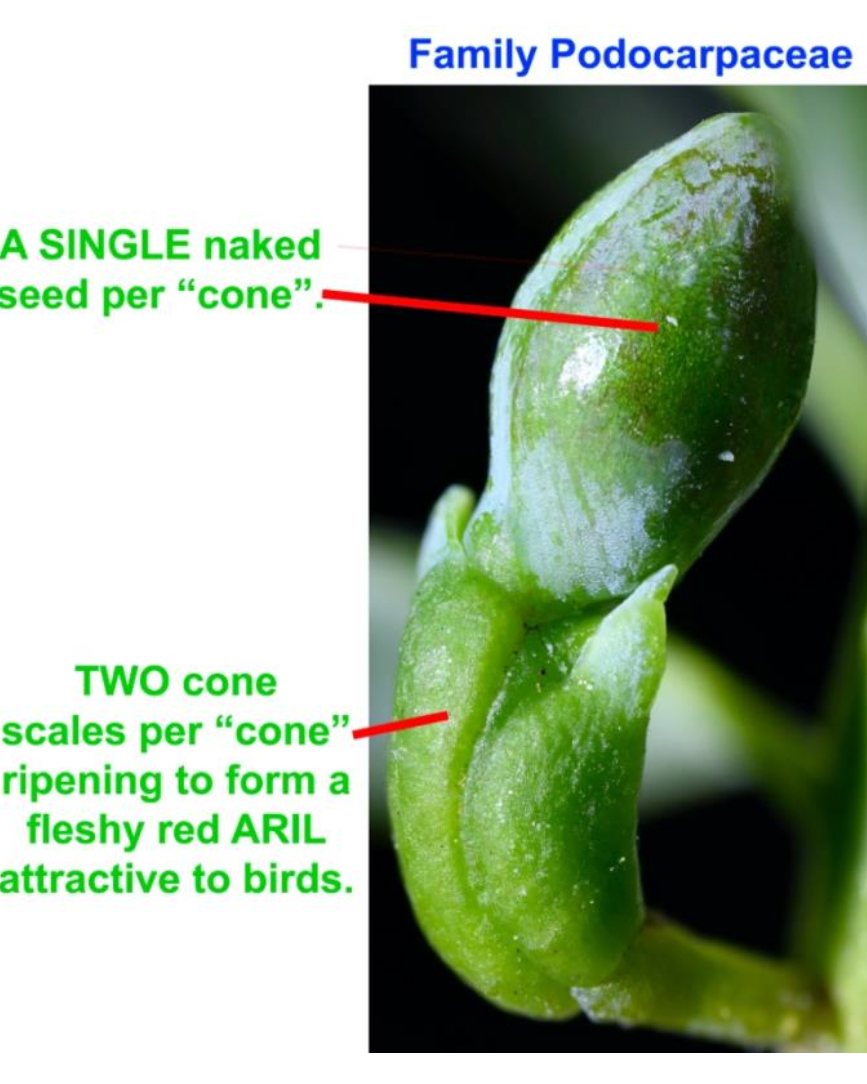

However, in the Southern Hemisphere the dominant endemic pines are the Podocarps meaning “Foot-fruit” referring to the way the naked seed sits on top of a round fleshy “fruit” called an Aril.

This is how the female cones of the two families of pines compare:

Look out for the Kahikatea trees Dacrycarpus dacrydioides growing in the damp stream bed of the Nikau grove. The largest one produced fruit for the first time in 2022.

Kahikatea can grow to a height of 55 meters with a trunk exceeding 1 meter in diameter, and is New Zealand’s tallest tree species, even beating the mighty Kauri. It prefers to grow in damp swampy conditions and often lines riverbanks and other wet areas. In immature trees, the leaves are about 8mm long and lie in a flat plane along the twigs (see picture left). When mature the leaves are scale-like and are 1-2 mm long. (below left) The cone scales swell to form a red fleshy aril with the seed on top about 5mm in diameter. Birds like pigeons find them irresistible and eat them dispersing the seeds as they do so. The largest tree in the Nīkau Grove (along the Wattle Track) produced about 100 arils in 2022 which were eaten very quickly as soon as they ripened. I was lucky to catch just one to photograph! Kahikatea are often referred to as “white pine” due to its clean white timber. It imparts no flavour to food and was used to make butter boxes for export to the UK up to the middle of the 20th century. There are still a few old-growth remnants of kahikatea left in the Waikato.

Māori used it for carving waka and for making bird spears. Its length meant it was used widely for shipbuilding, but it is not as resistant to rot as tōtara. Only 2% of the pre-European kahikatea forest remains.

The Tōtara Podocarpus totara is found in several places on Tiritiri Matangi, especially on the Tōtara, Kawerau and Ridge Tracks. Look out for the characteristic brown stringy bark and bunches of stiff and leathery leaves 20 mm long NOT on a flat plane on its twigs like the kahikatea, but protruding in all directions.

Tōtara “cones” have two to four fused, fleshy, berry-like, juicy aril scales, bright red when mature. The cone contains one or two rounded seeds at the end of the aril scales. Tōtara can grow to 35m and its timber is favoured by Māori for large carvings, whare frames and waka building. The inner bark was used for roofing and for storage containers and the outer bark as splints to support fractured bones.

Some of the larger canoes carved from a single tree could hold up to 100 warriors. Natural oils in the timber slow down rotting. When Europeans arrived in New Zealand, huge areas of tōtara were felled to supply general building timber, railway sleepers, bridge and wharf timbers and telephone poles. The red arils are an important food source for both humans and birds, especially tūī. Tōtara wood is very tough and can be used to produce fire by friction where a pointed stick is scraped on a slab of softer wood such as māhoe and a glowing ember created.

Which animals found on Tiritiri Matangi today would have appeared around this time 250 million years ago alongside these trees?

The wētās belong to the Insect Order Orthoptera (meaning “straight wings”) alongside the locusts, grasshoppers and crickets. There are three species present on Tiritiri Matangi, the giant wētā (Deinacrida heteracantha), the ground wētā (Hemiandrus sp) and the Auckland tree wētā (Hemideina).

The female giant wētā can achieve a weight of 70 grams making it one of the heaviest insects in the world. All insects rely on an air-filled tracheal tube system to deliver oxygen to their internal tissues and remove carbon dioxide. This is not a very efficient means of gas exchange, and it limits the maximum size an insect can grow to. Our giant wētā are right on that limit. Consequently, they spend much of their time sitting motionless – a good way to avoid being eaten by a passing tīeke. When they do have to move, they can do so quite rapidly but for a short time only before having to rest and recover.

There are eleven species of deinacrida giant wētā in New Zealand, mostly restricted to mammal-free islands. On Tiritiri Matangi we have the Little Barrier giant wētā Deinacrida heteracantha translocated here in 2014. At one time this species was widespread from Northland to Auckland. It probably reached Tiritiri Matangi and Hauturu during the last Ice Age 11,00 years ago when sea levels dropped and Tiritiri Matangi was a hill surrounded by forest on flat coastal plains.

One South Island species is an Alpine specialist and is capable of recovery after being frozen solid when temperatures drop below -5 C. These wētā are good examples of island gigantism. This is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. There are several possible reasons for this, a lack of predators on isolated islands allows larger less nimble individuals to survive that would otherwise have been eaten. Larger bodies are better able to store food and maintain a constant internal temperature giving a survival advantage. Other examples in New Zealand include takahē and moa.

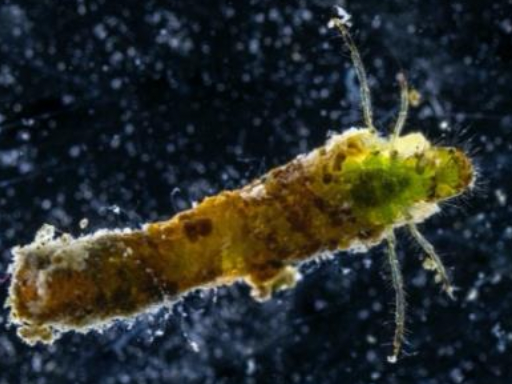

The Caddisflies (right) are another ancient group of insects that appeared around this time. Caddisflies belong to the order Trichoptera (meaning ”Hairy wings”). In New Zealand, we have many freshwater species and even five species of marine caddisfly, one of which, philanisus plebeius, is present on Hobbs beach living amongst the rockpools. Adult caddisflies are poor flyers with more than a passing resemblance to small moths. Adults lay their eggs within the bodies of cushion stars where the larvae develop for a time, eventually emerging by burrowing out through the mouth of the starfish, and then building a protective case of sand grains and silk to protect and camouflage themselves. In rockpools, they graze on red encrusting coralline algae and the diatoms that live on them. They pupate amongst the seaweed and emerge as a non-feeding adult to mate and repeat the cycle. Marine insects are incredibly rare and these caddisflies are found nowhere else on Earth.

Divaricating theories

Divaricating Theories

The puzzle of our small-leaved shrubs, moa and the ice ages

Author: Warren Brewer

Visitors sometimes comment on the marked presence of small-leaved, twiggy shrubs in our forest. Our flora contains a high proportion of these small woody shrubs which have a tight interlocking branching pattern. They are called “divaricating shrubs”. They have small leaves and tough wiry stems with a dense meshwork of branches with multiple growing points inside the shrub. They often have a brownish colour, giving an almost dead-looking appearance.

Some of our trees also pass through a divaricating juvenile stage, changing to a less tangled normal growth above 3m height. These plants all lack sharp spines. Collectively they are a special New Zealand feature. Our flora contains over 50 species of these divaricates (about 10% of all our woody plants). How has this growth pattern come about?

Two theories have been postulated:

1. Browsing Moa:

This huge two-legged bird came to occupy the role of a four-legged grazing mammal in New Zealand. It would have spent many hours picking leaves and twigs off low trees and shrubs. Moa favoured fertile river flats, forest edges and wetlands rather than deep forests. Highly palatable and nutritious shrubs growing in this habitat would have suffered extensive damage from these birds. They, therefore, had to evolve a mechanism to survive – hence their divaricating nature. Small leaves and a brownish colour would have made them look less attractive and dense interlocking branches would have deterred browsing. The lack of thorns and spines can be explained by the fact that whereas they would be effective at repelling the sensitive lips and tongue of a browsing mammal this would not work when dealing with the strong horny beak of the moa. Its beak would have acted like secateurs nipping off thorns etc which would have been easily crushed by the stones stored in its gizzard. Those trees with a divaricating juvenile form would be able to change to the adult stage above 3m height which would be out of reach of the largest browsing moa.

2. Climate Change:

The last ice age (Pleistocene) circa 2 million years ago caused world climates to go through a series of fluctuations with long cold glacial spells interrupted by warmer interglacial. It was a highly significant time for the final moulding of New Zealand’s present flora. Our vegetation lost the last traces of its Australian look (known that eucalypts, proteas etc once grew here from the evidence of fossil pollen deposits). The small-leaved divaricating form would be well designed to adapt to the cold, windy arid climate prevailing. This theory suggests that the growth form would act as a defence against wind abrasion and frost damage as the whole plant may have acted as a heat trap keeping delicate growing points within a protective shield. Small leaf size would have led to less moisture loss through evaporation thus counteracting the arid conditions.

Botanists continue to argue these two theories. Perhaps they both contain merit and actually reinforce each other as the need to grow this way would have been even greater if it helped plants to survive both adverse climate change and excessive moa browsing.

History of Wattle Track

History of Wattle Track

Author: Ray and Barbara Walter

Sourced from Dawn Chorus 70, August 2007

There seems to be varying commentary on the history of Wattle Valley. Here is the account of this famous walkway.

Wattle Valley formed part of the Lighthouse Keepers cow paddock and was fenced off from the main farming block until the 1970’s. It was not grazed from approx. the 1950’s and so it naturally regenerated in mostly, mānuka, tī kōuka/cabbage tree and Harakeke/flax. Big Wattle Valley was mostly tī kōuka and Wattles.

The wattles are from a Lighthouse Keepers gardens shelter belt. The 1940 aerial photograph shows 6-8 wattles and 2 fig trees at the bottom of the valley. From these few wattles, Big Wattle Valley was soon populated with further wattles. When the planting programme began they were left as they gave a rich source of nectar for korimako/ bellbirds and tūī. This was one of the major sites for students studying korimako.

As the bush has regenerated the wattles, being light-loving plants, have reduced and also the Australian Quail scratched the germinating seedlings.

Some plantings were made in Big Wattle Valley to increase the plant diversity which consisted of a small number of karaka, puriri, kawakawa, broom, pittosporum umbellatum, rhabdothamus and kōwhai. In the swampy area a few nīkau and kahikatea were planted at the seaward end of the valley. Two specimens of elingamita johnsonii were also planted.

The ridge between Big Wattle and Little Wattle which was covered in large stands of Japanese honeysuckle, once the honeysuckle was reduced it was planted with puriri and rewarewa. The seaward end of the ridge was the largest last planting in the ten year plan on the Island in 1994 and consisted of kara, mānuka, puahou/ five finger and kōwhai. Total number of plants in both valleys was no more than 400.

In the Little Wattle Valley only a few trees were planted consisting of puriri, rewarewa, pigeon wood and in the valley bottom kahikatea. The lower seaward end of the valley was not planted because it contained one of the last remnants of the native buttercup.

When tīeke/saddleback were first released in 1984 these valleys soon contained the densest population of tīeke. When Phil Cassey did his research on tīeke density he colour banded over one hundred birds. The original female in Big Wattle from Cuvier Island lived to the age of 21 years having had 3 mates! As the planted bush established, birds from this area moved into these new areas.

Ray and Barbara Walter

Former lighthouse keeper, Ray Walter, is somewhat of a unicorn. Having spent 30 years in the lighthouse service, he made the switch to managing the nursery. In 1980 Ray became the first ranger on the island. With his wife Barbara, they recruited hordes of people to create tracks and re-forest Tiritiri Matangi. Since then, Ray and Barbara have spearheaded the project.

Once the island was forested, Barbara helped to turn the tree planters into a group of dedicated guides. The creation of the sanctuary and the dedicated troupe of guides who tell its story has created a legacy which will surely last as long as the island itself. Ray and Barbara retired from DOC in July 2006 although they are often seen on the Island volunteering.

Tīeke mystery

Tīeke mystery

Author: Kay Milton

Date: August 2023

Header Photo Credit: Lucas Mugier

Something off has been happening in two of the tīeke nest boxes on Tiritiri Matangi. It was shared in our Tiritiri Matangi magazine, Dawn Chorus 124 (February 2021), that when Barbara Walter checked a box in early December 2020, two birds left as she approached. She found it contained six eggs (the normal number on Tiritiri Matangi would be two or three), and one of them was white (tīeke eggs are normally pale fawn with darker speckles)!

When the box was checked again on 16 December there were just three eggs. The white one and two of the others were missing. When we looked back at the photo of the six eggs we realised that the other two eggs were also unusual – they had a mixture of dark and light patches rather than speckles.

What appears to have happened is that two females chose the same box, one or both of them built a nest and both of them laid in it. Both incubated for a while, and then one of them removed the eggs that were not hers. We assume she was able to tell which these were because of their appearance, though there may be other clues we don’t know about. Although the victorious female went on to incubate the remaining eggs, they didn’t hatch.

Shortly after the nest failed, a new one was built in a box just a few metres away, and both females moved in there. This time the maximum number of eggs recorded was five on the morning of 7 January, but it was down to four by that afternoon, two normal ones and two abnormal ones, including a very pale one.

By 13 January there were just three complete eggs. The pale one had broken and its shell had stuck to the other abnormal egg. By the afternoon of the 21st, another of the normal eggs had disappeared and those that were left were cold. It looks like neither bird has won this contest.

The saga has moved on

In December 2022, in an attempt to learn more, a trail camera was trained on the box, triggered by movement to take a series of short videos during daylight hours. It did not pick up any eggs being removed, but it captured a number of apparently aggressive encounters outside the box, in which one bird chased another away. Since the birds are not banded, we cannot tell whether it was always the same bird doing the chasing. Nor can we tell whether these encounters were between the two females, or whether one or more males was involved.

The saga has moved on, and the mystery has, if anything, deepened. There was no sign of eggs being removed in daylight, so it could be happening after dark, when tīeke are assumed to be roosting quietly. We hope that next season will provide further opportunities to study this unusual case.