My first working weekend

My first working weekend

Author: Meredith BloggDate: 13 November 2023

Tiritiri Matangi sure lives up to its English translation…by blowing me away every time!

This weekend I had the privilege of participating in my first Working Weekend. Surrounded by long-time, seasoned volunteers and an absolute abundance of wildlife I learned so much (and gasped in wonder a fair few times!)

We got to work Saturday afternoon, divvying up projects and making plans for our dream teams. As the newest volunteer I wasn’t sure what to expect but I was welcomed into the crew and felt right at home with Peter’s ‘Dad Jokes’.

The Tiritiri Volunteers take balance very seriously so I had plenty of time to swim, nerd out on birds, walk in wonder and enjoy the extraordinary beauty and bounty of the island. The before and after photos above show how much work we got done, and we sure had a great time doing it!

Thank you to all the volunteers who have put in years of hard work to make this island what it is: a safe haven and a magical place for all the species who live, work, volunteer and visit! Your wealth of knowledge, commitment and care are so deeply appreciated.

A day in the life of the hihi team (October Edition)

A day in the life of the hihi team (October Edition)

Author: Emma GrayDate: 2nd November 2023

Photos and video taken by Emma Gray

Our hihi team has settled into its semi-permanent form as our hihi intern Maude joins us for 2 months from Switzerland. Other hihi sites often have students from the UK, USA and across Europe conducting research or interning for fieldwork experience.

Hihi continue to influence and inspire people across the globe as a model species for conservation and adaptive management. Adaptive management is the process of changing species management according to their needs based on both monitoring and research to increase species’ condition and survival. One example of adaptive management for hihi on Tiri is the provision of sugar water. Other supplementary foods have been trialled, however, those trial food diets paled in comparison to the provision of sugar water. Sugar water acts as supplementary nectar when natural food is not available, and has also been found to boost reproductive success and help our hihi babies grow big and strong.

Speaking of hihi babies, our first wave of hihi babies has started to hatch. The females seem to be incubating the eggs a little longer than the expected 14 days, likely due to the ambient temperature. As long as the eggs hatch at all, that’s all I ask for. The rest of the females seem to have taken a pause in nest-building activity or laying eggs despite the nests being ready. This is likely due to the windy wild weather we seemed to have at the end of September/start of October putting off our breeding females.

There is no shortage of hihi sightings as the sugar water uptake has exponentially increased going from 1 litre in a day to 10 litres a day at some hihi feeders. Last month saw the lowest consumption this year at only 155 litres total, while October is back amongst the middle ground at 756 litres total. We continue to argue with the tūī guarding three of our six feeders. This is also contributing to the large amount of sugar water consumed at other feeders as they all gather away from the aggressive tūī.

Emma continues to be impressed as the females never make her wait long when coming to check the nests. While females are incubating you could potentially be waiting up to an hour for a female to leave the nest to discover what she has underneath. Emma waits for only a few minutes, so far the maximum is 22 minutes, for females to hop off the nest and show her what is underneath. Some females are a lot quieter when leaving the nest, and others make a bit of a ruckus if they spot you and spread their wings to make themselves look bigger as they attempt to chase you away.

No harm comes to the birds, we quickly peek inside the box to know what is going on and leave the female alone until the next check in a few days. Sometimes we even see the males helping to feed the chicks, which is a surprise as the females do most of the work. Hopefully, next’s month update will have many more eggs and hihi babies to report back about.

Citations for supplementary feeding trials for hihi

Ewen, J. G., Walker, L., Canessa, S., & Groombridge, J. J. (2015). Improving supplementary feeding in species conservation. Conservation Biology, 29(2), 341-349.

Armstrong, D. P., & Ewen, J. G. (2001). Testing for food limitation in reintroduced hihi populations: contrasting results for two islands. Pacific Conservation Biology, 7(2), 87-92.

Walker, L. K., Armstrong, D. P., Brekke, P., Chauvenet, A. L. M., Kilner, R. M., & Ewen, J. G. (2013). Giving hihi a helping hand: assessment of alternative rearing diets in food supplemented populations of an endangered bird. Animal Conservation, 16(5), 538-545.

Castro, I., Brunton, D. H., Mason, K. M., Ebert, B., & Griffiths, R. (2003). Life history traits and food supplementation affect productivity in a translocated population of the endangered Hihi (Stitchbird, Notiomystis cincta). Biological Conservation, 114(2), 271-280.

Mather, E., Fogell, D. J., McCready, M., McInnes, K., & Ewen, J. G. (2021). Testing management alternatives for controlling nest parasites in an endangered bird. Animal Conservation, 24(4), 580-588.

The brightest in the land

The brightest in the land

Author: Alasdair BaxterDate: 30th October 2023

The video was recorded on my phone on a trip to Tiritiri Matangi over Christmas – I stayed the night and guided both days.

I tried to get snippets of film so that it looked like I was walking along to Hobbs Beach and then up the Wattle Track to the lighthouse (which you will see flashing at night). Then I filmed a walk back to the wharf the next day and, of course, the ferry leaving the wharf. I was lucky to see kōkako up close on the first day. I deliberately avoided shots of people in the film (although you might be able to spot one or two if you look very carefully).

I wrote the song’s chords and melody first and then decided the story of the lighthouse would be a good subject for the song. Anne Rimmer’s Tiritiri Matangi book helped me with a few of the lyrics. I came up with a rough arrangement and then we all added our many instruments to the recording. Emily Allen did a great job arranging her string parts and playing and adapting the traditional Irish reel which is featured in the song. Our band hoop plays regularly in Auckland and runs the Ministry of Folk in Mt Eden (look us up on Facebook :-))

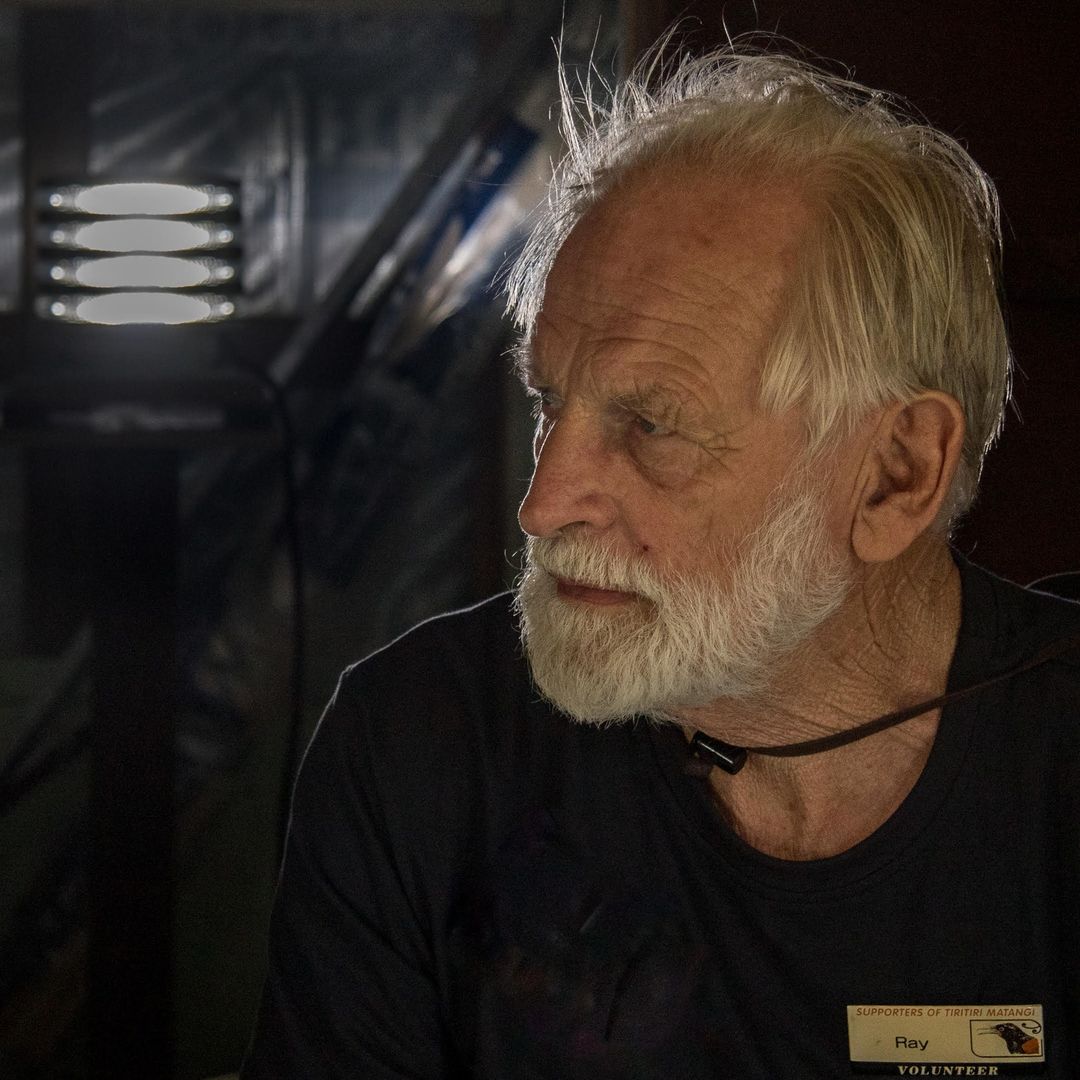

Passing of Ray Walter

Passing of Ray Walter

Author: Ian AlexanderDate: 23rd October 2023

Header Image Credit: Jonathan Mower

Featured Image Credit: Martin Sanders

It is with sadness we are informing you of the passing of Ray Walter. He served as lighthouse keeper, ranger, supervisor of the Island Conservation Project, committee member of SoTM, and a leader of many of the infrastructure projects including, most recently, the lighthouse museum.

Ray arrived as lighthouse keeper in 1980 at a time when the automation of lighthouses in NZ was already in progress, and by 1984 he was out of a job. However the commencement of the Island Conservation Project provided an opportunity to work as a supervisor for Lands and Survey, (later Department of Conservation) as a Ranger and he took over management of the Project in 1985. His legacy can be seen in the 283,000 trees planted on the island, resulting in the rich diversity of forest which now covers much of Tiritiri Matangi, and wildlife introduced including many endangered bird species whose unique calls today resound across the island, especially at dawn.

Ray, together with his wife, Barbara, were DOC rangers for 26 years, until they both retired from the day to day operation of the island in 2006. During this time boardwalks were built, tracks constructed across the island, as well as other important infrastructure. Another significant activity was their introduction of guided walks for planting volunteers and visitors which commenced in the late 1980’s and continues as a major attraction for both local and international visitors.

With such a contribution over so many years, a single book would never be enough to cover Ray’s significant contribution to Tiritiri Matangi island. The words used to describe our open sanctuary – “a conservation success story of international significance “ is also a fitting tribute to Ray Walter’s involvement in the development of the island.

Our condolences to Barbara and his family at this sad time as we all remember an extraordinary man whose incredible achievements will forever be part of the Tiritiri Matangi conservation project story.

Ian Alexander

Chairperson

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Inc

Photo credits:

Shaun Dunning

Simon Fordham

Geoff Beales

Neil Davies

Jonathan Mower

Martin Sanders

Neil Mitchell

Ian Higgins

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives

The largest centipede in New Zealand

The largest centipede in New Zealand

Author: Jonathan MowerDate: 17th October 2023

Staying overnight in the Tiritiri Matangi bunkhouse is guaranteed to give you unexpected moments but finding a large (15-20cm) hura/giant centipede (Cormalocephalus rubriceps) in the tea towel drawer, as Jackson Frost recently did, is elevating unexpected to another level.

Native to New Zealand and Australia, this is the largest centipede in New Zealand. Present in North Island and smaller offshore islands, they are usually found beneath rotting logs, stones, and decaying vegetation.

The giant centipede belongs to an order known as Scolopendrida, a group that includes the largest and most fearsome centipede species, all of whom have 21 pairs of legs (1 pair per body segment). Centipedes always have an odd number of pairs of legs, and despite their name, none of the centipede orders actually have 100 legs.

Their legs vary in length depending on where they are located on the body. This is thought to prevent legs from becoming tangled while moving at speed.

The most striking example of leg modification occurs with the first body segment’s legs, which form an evolutionary novelty** known as forcipules. These are powerful, sabre-like pincers that crush and incapacitate their prey while delivering poison through a duct located at their sharpened end.

Very active nocturnal hunters, they are a voracious predator of small prey such as insects, worms, molluscs and other invertebrates which they locate with their highly mobile, backward pointing, segmented antennae, and disc like Tömösváry organs*. Although these centipedes do have visible eyes, (ocelli), their vision is poor.

Large adults (>25cm) are known to eat small vertebrates such as reptiles and amphibians. However, due to predation on the mainland by introduced mammals, larger specimens are usually only found in mammalian predator-free sanctuaries and on offshore islands.

Despite their voracious nature, female giant centipedes are highly protective parents. Laying clusters of eggs within cavities they excavate in the soil, the female will wrap her body around the egg mass until they hatch into miniature versions of the parents (though lacking sexual organs), a process known as incomplete metamorphosis. She will then continue to protect her young in this way, sometimes even carrying her young when she moves, all the while protecting them with her forcipules.

Though the forcipules are quite capable of delivering a painful pinch (not a bite as they are not mouthparts) to anyone unwise or unlucky enough to handle a giant centipede, this is only a defensive response that will seldom result in serious side effects. As with all our native fauna, it is best practice not to handle these animals.

It is likely this centipede had been out hunting and only entered the dark tea towel drawer to escape the light. After having been photographed, it was released into the (relative) safety of the forest soon after this photograph was taken.

*Tömösváry organs are located near the antennae’s base. They are thought to detect vibration, humidity, and gravity.

**An evolutionary novelty is an attribute that has evolved only in one group of organisms

Header Photo credit: jacksonfrost.nature

Booking the Tiritiri Matangi Bunkhouse

The bunkhouse is the only accommodation on Tiritiri Matangi. It is a communal facility and has limited availability as it is primarily used by volunteers and students carrying out work on the island.

Facilities

- Gas stove and oven

- Microwave oven

- BBQ

- Two fridges and a freezer

- All cutlery, crockery, utensils etc

- Pots and pans

- Dishwashing liquid, dish cloths and dish brushes

- Tea towels

- Drinking water (rainwater from the tap)

- Two hot showers

- Two toilets (toilet paper provided)

- 3 rooms for public use, with 15 bunk beds in total:

- Room 1 Kahu: 4 beds

- Room 2 Kokako: 5 beds

- Room 3 Tuatara: 6 beds

Being a guide on Tiritiri Matangi Island

Being a guide on Tiritiri Matangi Island

Author: Bob BickerDate: 17th October 2023

School in Southampton included sport. I would be told tomorrow we’re going to The Common, a large, forested area with sports fields, reason? to play cricket, the very word made me yawn. They’d put me in a fielding position, the ball would whistle by, I was oblivious to it as I’d be looking the other way, watching squirrels, birds and occasionally a fox. How nature worked fascinated me then, nothing’s changed.

A few years later I found myself in Alderney for ten years, the northern most of the Channel Islands. One job I had there was crew on a lobster boat pulling the pots. Just north of the island was a small islet, Burhou which in the season had Puffins. I’d say to the skipper ‘ can we land there ’, seeing these fed my passion. By default, I became the person who you took injured birds to. Locals would knock on the door to hand me a wounded Cormorant, Razorbill or Guillemot. I had scant knowledge of how to help these creatures but did have a reasonable degree of success, one I’m still proud of.

Go forward a few years and I’m on a ferry approaching Tiritiri Matangi to learn how to guide and then hopefully impart knowledge to our visitors of our flora and fauna and how it works and importantly how we need it. I had scant idea of the steep learning curve I was about to embark on. Many of those involved in the island are what one would deem as academics, highly qualified in their field, their vital input to a large degree is behind the scenes. With 5 times round as a buddy guide, I went solo. Having no qualifications in relevant fields, my challenge was to glean facts and figures from those experienced and seek to present that in layman’s terms; this is ongoing. Apart from the knowledge, it’s vital to develop one’s own style, a mantra from the guides who taught me, never a truer word spoken. I showcase what others have created, something I do with pride.

Bob

Guiding

One of our most popular volunteer opportunities is guiding. Guides must undertake at least six buddy training sessions before they become a fully-fledged guide. Although this position is well suited to someone with experience in the conservation field, passionate volunteers with reasonable fitness levels are most welcome to sign up, as full training, ongoing support and development is provided.

People power

People power

Author: Stacey Balich

(Information sourced from 'Long term value of engaged, skilled, citizen scientists' Mel Galbraith and Hester Cooper)Date: October 2023

When I first visited Tiritiri Matangi Island, I was amazed by the place. As soon as I stepped off the boat onto the wharf, the sound of bird song was amazing and I knew I was in for a great day. My family and I spent a wonderful day exploring most of the Island, taking in all the beautiful sights and sounds of nature. I fell in love with the Island and knew that I wanted to come back again and again. After visiting a few times, I decided to become a volunteer guide and that’s when I was truly inspired because of the people I was about to meet and get to know. It’s amazing how much you can learn and appreciate when you become a part of something like this.

The Tiritiri Matangi Island project has been around for decades, and it stands out from other conservation initiatives because it involves a volunteer workforce. Unlike other restoration projects where academics and government scientists hold all the power, the volunteers are given the responsibility to lead projects and are treated as true partners. Mel Galbraith and Hester Cooper discuss this approach in their article, ‘Long term value of engaged, skilled, citizen scientists’. The planting program began in 1984, and volunteers were involved from the start. This was a controversial approach in New Zealand at the time because it wasn’t fully supported by government agencies. However, over time, agency philosophies have changed due to the persistence of volunteer engagement and their critical role in conservation management (Galbraith & Cooper). I encourage you to download this article, see below.

Right image: One of the SoTM volunteers guiding a group along the Wattle Track to the lighthouse. Peter is explaining the use of the hihi nest box.

Credit: Peter Flynn

The ongoing partnership between ecological science and non-professional practitioners has been crucial in the management of Tiritiri Matangi Island and its protected species. The New Zealand Maritime Museum has also played a role in the restoration of the island’s lighthouse, with recent efforts focused on the installation of a mast. The planning and organization of these restoration efforts have been led by the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, exemplifying the importance of community involvement in the conservation of our natural world and heritage.

As I speak to different volunteers, I can sense their love for Tiritiri Matangi Island and its protected species. Their passion is reflected in their smiles and the way their eyes light up as they talk about their favourite areas of interest. For instance, the coordinator of the kōkako team is so happy when discussing these birds, and her enthusiasm is contagious. In the lighthouse museum, the volunteers are equally knowledgeable and passionate, sharing amazing stories about the items on display and their restoration efforts. When I ask volunteers about the working bees that take place on the Island, they proudly tell me about their contributions, such as clearing up a track or rebuilding a path. I love hearing stories about the early days of planting on the Island! There’s something truly special about seeing how the community came together to make it all happen. And those photos from that period are simply eye-opening because they capture the spirit of growth and progress that was happening back then. It’s amazing to see how far the Island has come since those early days and heartening to meet so many people giving their time in such a variety of ways to protect and conserve this beautiful place.

If you want to get involved in a leading-edge project then join the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi as you will be standing on the shoulders of true giants. Once you become a member you get four Dawn Chorus magazines a year and in these magazines are stories about what is happening on the Island. You will also be on the mailing list for when projects come up if this is something you would be interested in. There are so many ways you can contribute whether it is on or off Island.

The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy

The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy

Author: Emma GrayDate: 28th September 2023

Header image: John Sibley

The very first stint back on the island is a new level of busy. I always think I’m ready with my island feet until I fall over for the first time and bring myself back down to earth. The hihi team is very small at the moment as we perform our pre-breeding season tasks including the survey, sugar feeding handover from the rangers, and a lot of cleaning.

The pre-breeding survey entails 40 hours spent walking all the tracks and bush patches on the island, including spending time at the sugar feeders in both the morning and afternoon to see which adults are still alive and which juveniles from the previous season have made it through their first winter. Hihi juveniles have a 40% survival rate through the first winter, which we know due to our annual mark-recapture surveys. Mark recapture in the case of the hihi means banding all individuals with a unique band combination, most likely banded as chicks in the nest, and recording the individuals, their sex (in case we got it wrong) and their location/potential territory for the upcoming season.

The sugar water consumption is highest on Tiritiri Matangi Island during the winter (thank you to the island rangers who keep these hungry birds fed daily) unlike other hihi sites. This is due to the lack of natural food available over winter, while the fruits, flowers, and invertebrates that hihi feed on are numerous in spring/summer.

Once the 40 hours of the survey are complete, we’ve then got the task of cleaning out 200+ nestboxes so they are spick and span after being used as roosts over winter. Unless they are already occupied by other wildlife and the beginnings of the stick base for hihi nests.

The hihi have been surprising us this year by laying eggs almost a whole month early. They are keeping us on our toes and making the most of the abundant natural food available. Currently, the hihi aren’t spending much time drinking the provided sugar water at the hihi feeders and instead determining social hierarchy and territories. The male hihi are displaying in their territories, while the females are either getting ready to lay eggs or still picking their partner for the season.

The females usually build their nests slowly during late September and early October with the first eggs typically laid around mid-late October. Our first-year females often don’t attempt their first nests until December! Looks like we have an interesting season ahead.

From planting some of the first trees to using them for shade from the sun

From planting some of the first trees to using them for shade from the sun

Authors: Students from St Cuthbert's Year 7Date: Thursday 21st September 2023

Header image credit: Martin Sanders

“Today St Cuthberts Year 7 visited Tiritiri Matangi. When we arrived, we admired the crystal clear water and the beautiful greenery that surrounded the island. As we were guided around the Island by the kind guides, we experienced all the beautiful songs of the birds. We learnt so much about all the different kinds and species of birds, trees, plants and so

much about the history of the Island. It was very inspiring to know that our school was part of restoring this beautiful Island. We had so much fun learning about all the cool facts our guide taught us. Our favourite fact was that some wētās, if they land on your hand, it feels the same as when your fingernails dig into your palm.

Thank you so much for having us, we loved the experience.”

Chloe and Lucy

“Our trip to Tiritiri Matangi was spectacular! We learnt various facts about the wildlife there, all sorts of birds and most importantly we learnt about the inspiring history of the Island. Many people used to come to Tiritiri Matangi to plant trees and help make it the beautiful Island you see today. If you do something good, people will remember you! The Island of Tiritiri Matangi is invasive pest-free and definitely worth visiting. It is so interesting and such a beautiful place to visit.”

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Sasha and Lila

“Our school trip began with fog so thick it looked like someone had placed a dolly blanket over Auckland. On the ferry, we could only see the expanse of water and fog and smell the salty air. When we got to Tiritiri Matangi the first thing we noticed was the perfectly clear water that glimmered in the sunlight. When we stepped onto the dock a stingray caught our eyes, it was named ‘smoky’ by Pippa, a girl in our class.

Along our trail, we saw an absence amount of birds. A ruru, a kererū, tūī, tīeke and a kōkako; one of the rarest birds to see. We also saw three wētāpunga, the heaviest insects in the world, and one female tree wētā.

At the top, there was a beautiful view of the forest that was planted by many hardworking volunteers. Our trip was amazing because of our volunteer guides, we will be coming back soon.”

Chloe and Zytak

“Going to Tiritiri Matangi was truly an inspiring experience. We got to explore and learn about all the different types of beautiful birds, insects and plants. We felt proud knowing that in the past St Cuthbert’s planted many trees. Our amazing guide, Neal led us along the way and showed us all the living things around us. We experienced things that we barely get to appreciate and see in Auckland. On the boat ride there, we got to spot the jellyfish. As we were walking around the Island pathways, we could hear all the birds tweeting amongst each other. We also got to admire the breathtaking view and look at the different equipment that was used ever since 1987.

Our trip to Tiritiri Matangi was unforgettable and we want to thank all the teachers and staff at the Island who dedicated their time to make this an unforgettable memory.

Thank you so much this trip!!!”

Mahnoor and Beau-Ruby

“Our visit to Tiritiri Matangi was eye-opening and we will definitely remember it. We heard and experienced the unique wildlife of the Island. We found this trip to be inspiring and we’ve made so many special memories. It was really amazing to be in the same place that St Cuthbert’s old girls had been and had planted trees in many years ago. We hope that we can make such an impact on our planet as they have.

The St Cuthbert’s students would like to recognise and acknowledge all the staff and volunteers at Tiritiri Matangi who went out of their way to show us around and make this experience one to remember”

Ainslie and Kalila