With Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forward

With Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forward

Author: Ian Alexander, Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Island Chair

Date: June 2024

Photo header credit: Geoff Beals

With Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forward, celebrating the past year and thinking of what can be achieved over the next year.

It has been a year of change for volunteers and staff on and off the Island. Having farewelled two of our beloved members late last year, we remember them – Ray Walter and Mel Galbraith, two men who contributed a life of service in many different ways to the development of our island conservation project. And there are others who have passed away during the year who in their own way have also contributed to the work of the Island.

Guiding both public and schools has continued to be a major part of the operations of Tiritiri Matangi as have efforts made by all our sub-committees and task groups across biodiversity, infrastructure, advocacy, education, fundraising, membership, retail and IT.

Climate has and will continue to dominate the Island ngahere and tracks requiring constant attention by our regular working parties and individuals.

Looking forward there remains much to do to ensure the proper care and attention to the Island’s flora and fauna and to continue to provide opportunities to everyday New Zealanders in citizen science.

Tiritiri Matangi island holds an appeal as a haven for New Zealand wildlife and humans to enjoy and our future role includes protection of this incredible taonga.

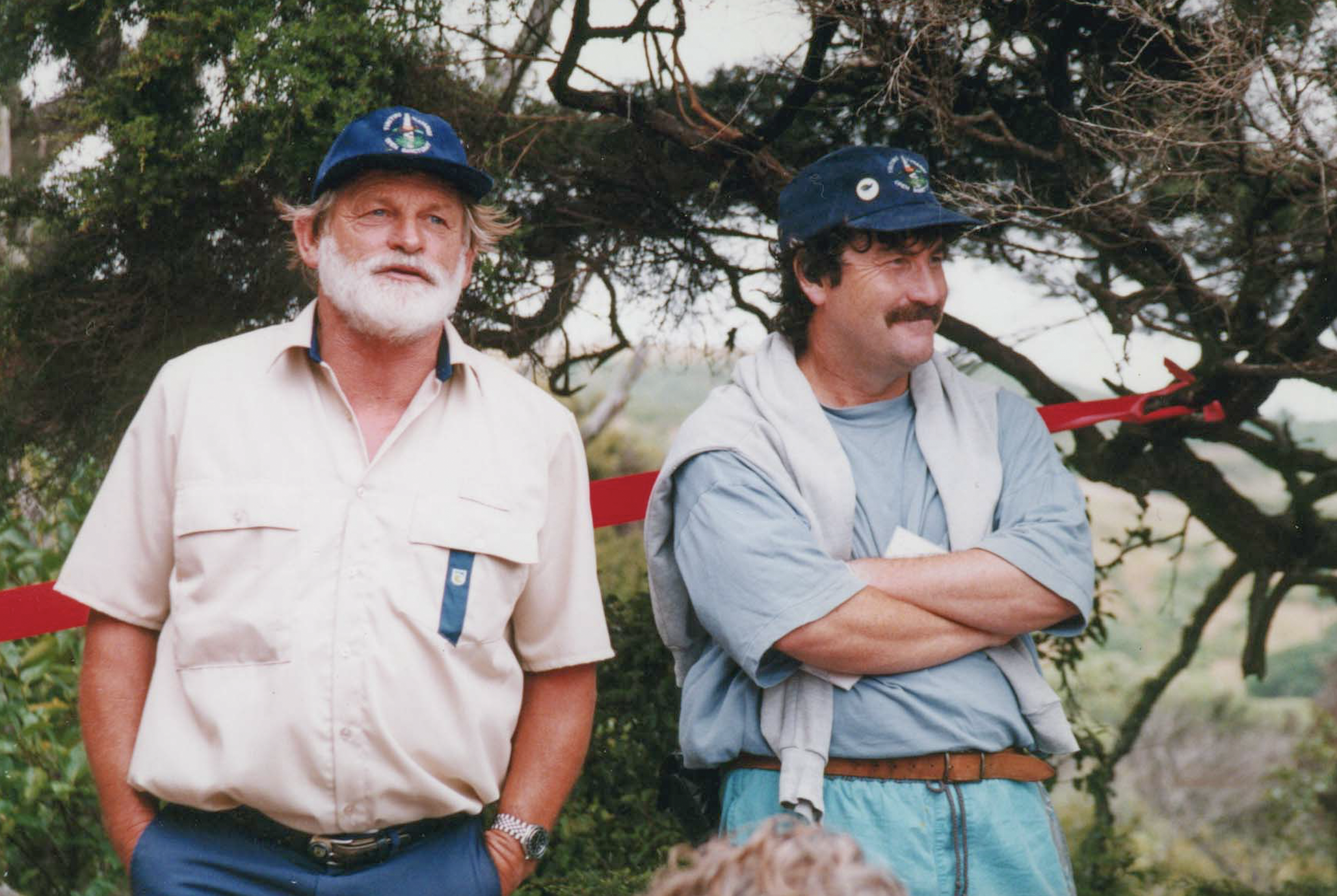

Left: Ray Walter, photo credit Martin Sanders

Middle: Ray Walter and Mel Galbraith at the opening of the Kawerau Track, photo credit from Tiritiri Matangi archives

Right: Mel Galbraith.

He aha te mea nui o te ao

What is the most important thing in the world?

He tangata, he tangata, he tangata

It is the people, it is the people, it is the people

Māori proverb

Meet the volunteers: Keeping it in the family – Davina, Diane and Bob

Meet the volunteers: Keeping it in the family – Davina, Diane and Bob

Author: Davina Bennetto

Date: June 2024

My time on Tiritiri Matangi started during the pandemic when my job in the travel industry quickly went from ‘very busy’ to ‘dead quiet’. With my wonderful parents Bob and Diane already volunteering on the island, it was something I too was interested in but never had the time – oh how quickly things can change! I registered interest and soon found myself working in the shop, caught up in the magic that is our little slice of paradise, realising just how therapeutic Tiritiri Matangi was. From witnessing takahē walk into the shop to seeing a pīwakawaka flying in only to sit on a coaster with a pīwakawaka on it, things you wouldn’t experience every day, I always left the island feeling a million times better.

The island became a place of ‘time out’ and a wonderful way to spend time with my parents. As the ferry docks, Dad will take a group on a guided walk, while Mum and I open the shop. Having the time to sit and enjoy the serenity during our lunch break together is so special and I will treasure these moments forever.

Now the borders have opened and kiwis are travelling up a storm, I still make time for my special Tiritiri Matangi days to disconnect from the busyness of life and appreciate what we have in our own backyard.

Tuatara—Ancient Escape Artist

Tuatara - Ancient Escape Artist

Author and photo credit: Jonathan Mower

Date: June 2024

Tuatara are the sole surviving member of an entire order of animals, the Rhynchocephalia, whose ancestors separated from those of the Squamata (lizards and snakes) in the late Triassic period, so about 240 – 250 m years ago.

Reaching total lengths of over 600mm, they are the largest of New Zealand’s endemic, terrestrial reptiles (some males recorded at a hefty 1.1kg), with their ridged tails accounting for slightly more than half of that total body length. Muscular and powerful, the tuatara’s tail plays a significant role in balancing locomotion, storage of body fat, and displays of dominance or physical defence.

To a superficial observer, the tuatara might be described as resembling a lizard, but in reality, there are significant differences between tuataras and other reptiles.

One similarity, however, is the ability to sever deliberately and then regrow part of their tail. The practice is known as caudal autotomy and is a defensive mechanism that allows them to escape harm or predation.

Why would you intentionally drop off part of your body?

On their island sanctuaries, kahu/harriers are significant predators of tuatara. They are also predated by other birds including karearea/falcons, kōtare/kingfishers, and possibly, ruru/ morepork and karoro/black backed gulls. Tuatara must also watch out for larger tuatara, giant centipedes, and mammalian predators such as rats, if they are present.

Severing a tail segment would allow a tuatara to escape a predator by distracting them with a small, wriggling piece of tail or by leaving the predator with a mouth full of severed tail as the tuatara escapes lethal harm.

Tail loss is an expensive process

Unlike many other reptiles, tuatara lack abdominal fat storage organs known as corpora adipose and instead store significant amounts of fat in their tails. This means tail loss sacrifices large energy stores and diminishes its ability to move at speed to avoid predators or confront rivals. This, in turn, can lead to reduced breeding success and diminished abilities in behavioural signalling and territorial displays until a replacement tail can be grown. As regrowth is in tuatara time, that is, exceedingly slowly, the costs can take a significant amount of time to recoup.

How does the tail separate?

If you were to look closely, you would notice a series of vertical creases running from the tail’s tip toward the abdomen. Each of the vertical creases is positioned between all the caudal (tail) vertebrae except for the 5-7 closest to the abdomen. These creases mark the shear points at which the tail can be intentionally severed.

You could assume the tail would be severed between vertebrae. However, that is not the case. Rather than splitting between the vertebrae, the tail instead separates when the caudal vertebrae bone shears in two as the skin splits, muscle segments separate, and the spinal cord and blood vessels sever.

Replacing their tail

When the tail is severed, muscle contraction occurs, blood loss is staunched, and wound healing begins. Eventually, the wound site is covered by epithelial cells and regrowth of the tail begins.

It would be more correct to say that the tuatara regrows ‘a’ tail rather than ‘their’ tail, for the tuatara cannot regrow a tail that is identical to that which was autotomised. Sometimes the tail can break at the site of the new tail, and the resulting regrowth forms a forked tail, and sometimes it may break again, resulting in a third end to the tail.

Rather than being built around a segmented bony skeleton, the new tail is built around an unsegmented tube of cartilage that lacks the fracture plates of the original. The new tail segments tend to be shorter, often with a ‘nub like’ appearance that lacks the complex colours and scale patterns of the original as well as the dorsal crest of scales and spines. The tuatara does however develop a significant amount of connective tissue, muscle mass and fat storage. All of this is a slow process however, very slow, that is to say, in tuatara time. It will take years for the tuatara to grow a tail that will fulfil its purpose as a fat repository and functional appendage for balanced locomotion, useful for behavioural displays and aggressive encounters, especially in males.

Why can’t they grow a tail like the original?

Though tuatara and lizards possess the ability to undertake caudal autotomy, the ability to regrow identical limbs is possessed by only one order of the super-class Tetrapoda (four legged animals), the urodeles, which includes axolotls, newts and salamanders.

It is thought that this ability was once possessed by the ancestors of most animals but interestingly, it is considered that all tetrapods possess the ability to do so as embryos but lose it as they mature.

Acknowledgements:

Tuatara: Biology and conservation of a venerable survivor. Professor Dr Alison Cree

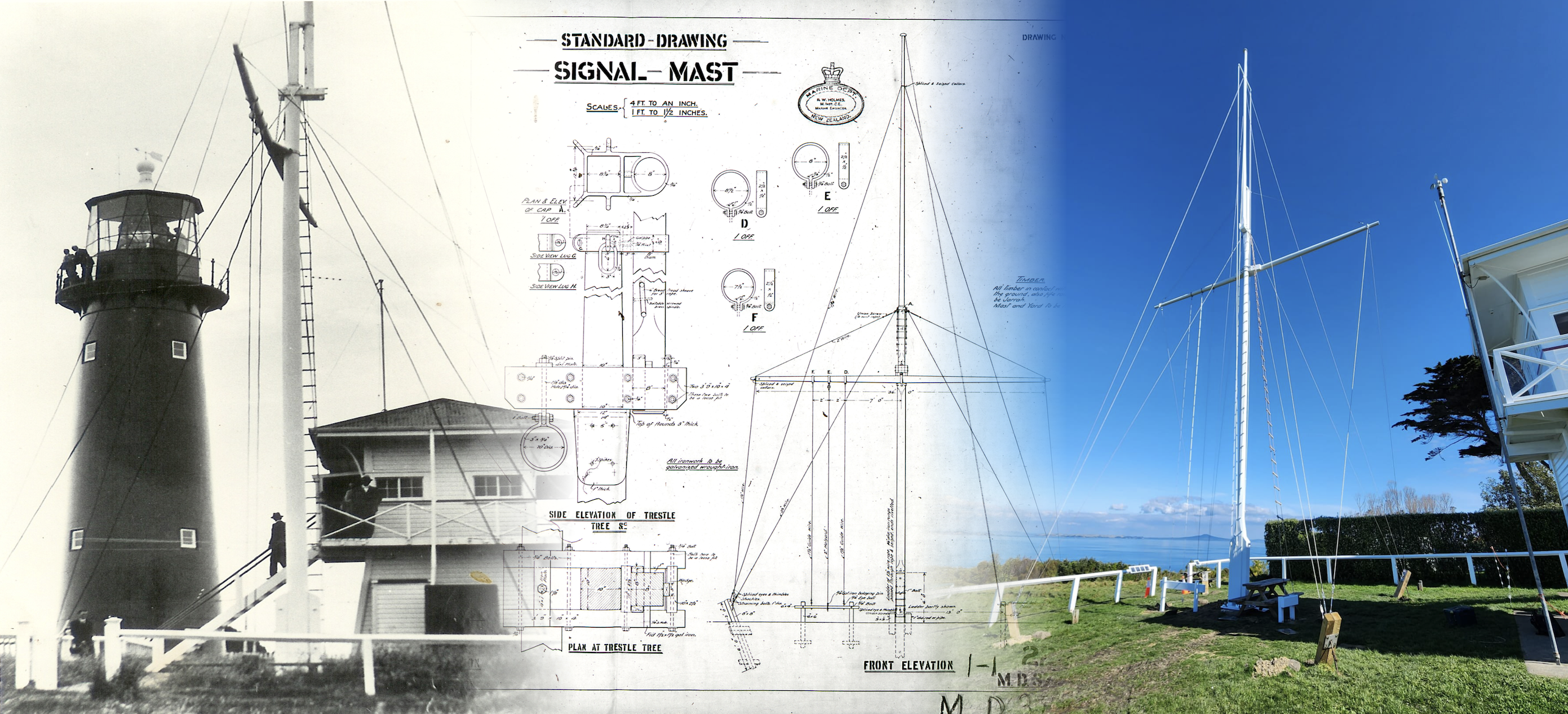

Tiritiri Matangi Island Signal Mast Reconstruction

Tiritiri Matangi Island Signal Mast Reconstruction

Author: Carl Hayson

Date: Taken from the Dawn Chorus, 135 November 2023

Header photo: Geoff Beals

The replica mast has been rebuilt to the exact specifications of the original structure which was erected in the late 19th century. It last existed in the 1940s but, along with all the other signal masts on lighthouse stations around the country, was taken down when manual signalling was no longer required. In the early 2000s, SoTM restored the 1908 watchtower which had fallen into disrepair, and this is now a popular attraction for visitors. The mast was an integral part of the original signal station, and when Ray Walter and Carl Hayson discovered a small section of the old mast in 2003, a plan was conceived to rebuild it.

Its original function was to provide shipping information to the Ports of Auckland in the days before wireless transmitters were available. Signalling was conducted with a combination of flags and woven baskets which were seen by a station on Mt Victoria in Auckland. At 25m tall, the mast is slightly higher than the lighthouse and can easily be seen from the sea.

To work out the original dimensions of the mast, measurements were carefully taken of the surviving piece of the old stay foundations. A Ministry of Transport sketch from 1913 was unearthed, and this assisted with the draft drawings for a new mast by the Flagpole Company, who were engaged to design the new mast to the exact dimension of the original one. John Haycock, the director and planner, spent many hours bringing the drawings up to the required specifications.

However, the biggest hurdle was to raise funds for this special project (cost estimated at $180,000), as most funding organisations do not fund this kind of restoration. Additionally, the original mast was constructed of kauri and jarrah hardwood, weighed 2.5 tons, and would have been very difficult to build and erect.

The project looked like it would not proceed, until our very capable Fundraising Manager, Juliet Hawkeswood, managed to obtain $40,000 from the Stout Trust and a further $5,000 from the Christopher Mace Trust. Quite a few Supporters had also made donations, but this was still not enough to proceed with the wooden mast. Then Forged Fabrications from East Tamaki, who had recently acquired the Flagpole Company, contacted us about making the structure in aluminium, a much lighter and stronger material. It would look just like the original and the funds that had been raised would be sufficient to cover the cost. This was accepted and, over the next 12 months, the mast took shape in their factory in Auckland. It was the largest mast they had ever constructed, and it took several attempts to get it right, which included bringing in specialist parts from Australia. In the interim, drilling equipment was brought to the Island to install new stays, a plinth was dug out by SoTM, and Coast Concrete were engaged to put in the concrete base for the tabernacle, which holds the mast in position.

When completed, the mast was trucked up to Whangaparāoa Peninsula where Matt Maitland from Auckland Council allowed it to be stored in Shakespear Regional Park. A helicopter from Skyworks was engaged to lift the mast to Tiritiri Matangi, where it was assembled, ready for placement.

Finally, the Skyworks helicopter lifted the whole mast, an impressive sight, and slotted it into position. The team from Forged Fabrications then set up the rigging and the mast was once again standing near the lighthouse station.

Ray Walter had found a 1931 admiralty book that listed the identification flags specific to Tiritiri and these had been made and were flown on the newly erected replica. Plans for the future include interpretation to show how flags and baskets were used for signalling, and displayed on special occasions.

Many thanks to Sheldon Bevan and Ryan Gouldstone from Forged Fabrications for the construction of the mast, Ian Higgins from SoTM for his organisation skills, Sarah McCready from Clough & Associates for the Heritage and Iwi consultation and planning, The Stout Trust for supplying the bulk of the funding, the Christopher Mace Trust, and John Haycock for the technical drawing work.

The kiwis are here

The kiwis are here

From the Tiritiri Matangi Archives

Editor: Zane Burdett

Bulletin No.14Date: August 1993

In fact, since the five pairs of little spotted kiwi arrived, they’ve been here, there and everywhere on Tiritiri – exploring what is now their new home.

They arrive on the 4th of July – ‘Kiwi Independence Day’. That day, over 500 people; babies, children, teenagers, adults, young and old, officials, sponsors, scientists, reporters and Yamagata whenua – had waited. They had waited together on a ridge under a great cloudy sky with a cool wind blowing – but the wait was worth it! The was the first public release of the little spotted kiwi. Maybe on this day the number of people in recent history to have seen a living little spotted kiwi in the feather had probably doubled!

The kiwis arrive by helicopter at about 3pm accompanied by representatives of Ngtai To a and Te Ottawa, tangata whenua of Kapiti Island, the Minister of Conservation Mr Denis Marshall and DoC staff. They were greeted by representatives of Te Kawerau a Maki, tangata whenua of Tiritiri Matangi. Following speeches by officials and Dell Hood and Mel Galbraith – 4 birds were taken by DoC staff and shown to the gathering. All the birds were taken to their released sites and placed into prepared burrows.

The arrival of the little spotted kiwi on Tiritiri was made possible by the Department of Conservation’s Kiwi Recovery Programme, supported by the BNZ and the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society and the commitment made by yourselves – the Supporters – to ensuring the viability of the Tiritiri Matangi project.

In the days following their release the birds’ nightly movements were recorded by Sibilla Girardet, an Auckland University post graduate student, assisted by Chris Te Pay. Shaarine Boyd of DoC monitored their roosting sites during the day.

In their first nights all the birds, except those in Bush 22, split up. It appears that the females remained relatively close to their release areas in comparison to the males who explored large areas of the island. One bird was recorded as having travelled from the North of the Island to the ligthouse and back again in one night.

Sadly, only days after their release one male bird died as a result of injuries received when its transmitter become entangled in vegetation. Because of this the remaining birds were re-captured and their transmitters were removed to reduce further risk of death.

Since then two birds, in addition to the Buss 22 pair, have got together and have been heard calling in duet (one after the other) – a sign of possible pairing as the birds are coming into the breeding season. It would appear the birds are settling in well.

Pukupuku/little spotted kiwi

Pukupuku/little spotted kiwi

Author: Jonathan MowerDate: May 2024

Header image: John Sibley

Island visitor Darren Markin recently captured this footage of a foraging kiwi pukupuku/ little spotted kiwi, while walking one night along Tiritiri Matangi’s Ridge Road. Being nocturnal by nature, footage of active kiwi is relatively uncommon, so his footage is a rare record of kiwi’s feeding behaviour.

Kiwi pukupuku/little spotted kiwi are the smallest of the 5 surviving kiwi species, with the larger females averaging 1350g/30cm. Once widespread in both the North and South Islands, human arrival in New Zealand saw them disappear from both islands and the species diminished to only a small population on Kapiti Island, the descendants of a small number translocated there in 1912.

Descendents of these survivors were first translocated to Tiritiri Matangi in 1993 when five pairs were transferred from the Okupe Valley, Kapiti Island to Tiritiri Matangi Island on 4 July 1993. Subsequent translocations have boosted their numbers on the island to the point that their calls are regularly heard and, as Darren’s video attests, seen by visitors walking at night. This video is particularly useful in showing how kiwi forage for food.

Kiwi use their bill to detect their prey (mostly small invertebrates such as earthworms and insect larvae) and are often observed moving through their habitat while gently tapping the end of their bill on the ground as they search for prey.

Recent studies have suggested they are using a process known as ‘remote touch’ where prey is located by micro-receptors located in pits found toward the end of their downwardly curved bill, which is particularly concentrated around a bulbous area located at the end of the upper bill (the premaxilla) which overlaps the lower bill. Detecting prey using sensory pits at the end of the bill is an attribute also found in shorebirds and ibis species.

Kiwi are unique in the avian world in that their nares/ nostrils are located near the end of their bill, rather than near the beginning leading to the belief that prey is detected by smell. However, recent studies are suggesting that although do have a well-developed sense of smell, it may be used more in social interactions and territorial boundaries rather than in foraging for food.**

Kiwi are a unique taonga well worth the huge amount of effort that has been dedicated to ensuring their survival.

*https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.2322

**https://www.aavac.com.au/files/2017-06.pdf

Video footage: Darren Markin

text: Jonathan Mower

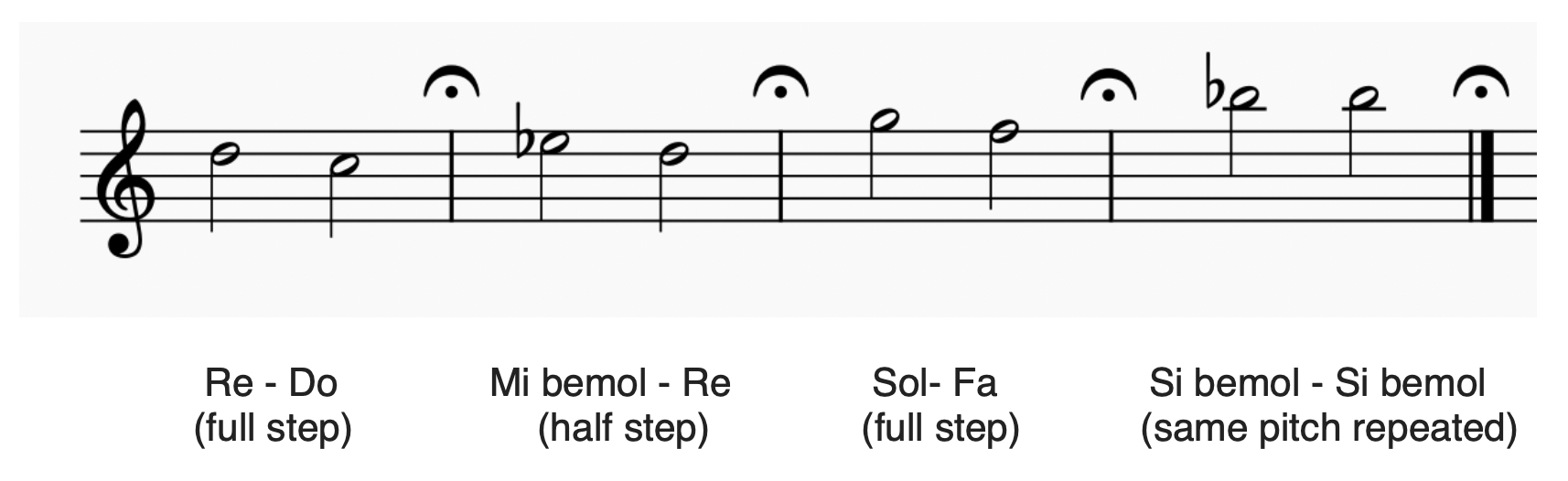

Kōkako Music

Kōkako Music

Author: Ran Kampel, Assistant Professor of Clarinet Baylor University School of Music Texas, United States of AmericaDate: April 2024

Header Photo Credit: Darren Markin

Last month my wife and I attended a guided tour with Bethny Uptegrove on Tiritiri Matangi Island. We loved the beautiful colours of all the birds and enjoyed observing them fly around and interact with each other, but what we found to be the most fascinating was the variety of sounds and the birdcalls we heard during our visit.

Above all these birdcalls stood out the remarkable call of the Kōkako. Its intricate call captured our attention from the first moment we heard it! My wife and I are classically trained musicians (flute and clarinet respectively), who played with orchestras all over the world. This pure melodic pattern of the Kōkako call was one of the most beautiful chants we ever heard in nature.

Bethny, our guide, shared with us that the call we were listening to is unique to this specific pair of Kōkako who are controlling this exact part of the island. Their call can carry for kilometers and is used to mark their territory. It would only change the moment the male were to lose its dominance to a younger Kōkako. She also shared with us that the call was split between the male and female Kōkakos, but it was very hard for us to differentiate the two and tell what was the call and what was the response.

The pitch accuracy and control of the Kōkakos call was remarkable. It was very tonal and was comprised of full steps and half steps. In western tonal music all scales are comprised of half steps and full steps between the notes. This beautiful melody we were witnessing was comprised of 4 distinct pairs of notes grouped together. Each time the group of notes started on a higher note than the group proceeding it with the last pair of notes repeating the same note twice:

The last repeated Si bemols were the least stable pitch-wise and got lower intonation-wise, which is surprisingly a common phenomenon in classical music (especially among students) to drop the “pitch support” at the end of the phrase. However, the impeccable pitch accuracy with each repetition of the kōkakos call was quite remarkable!

The sound quality of the kōkakos call reminded us of the tone of a glass harmonica or the sound one makes when running your fingers on the rim of a glass with some water.

It had a real transparent timbre, which gave it the very haunting colour of a surreal instrument.

Moreover, in contrast to most other birdcalls, which are very rhythmical with fast active measured repeating patterns, the kōkakos call was unique in its amorphous sense of time and undefined rhythms. The sense of pulse (time) of the call was very free and unpredictable. At times there were long-held rests (quiet moments) between each pair of notes which made it hard to predict when the next note of the call would happen. This absence of clear time gave the call a magical almost rhapsodic-like free-flowing mood, as if it was improvised on the spot.

I wish we had an opportunity to listen to a version of a different kōkakos pair and compare their melody with the one we heard. Next time you are in Tiritiri Matangi Island, try to capture their call and compare it with “our kōkakos call”.

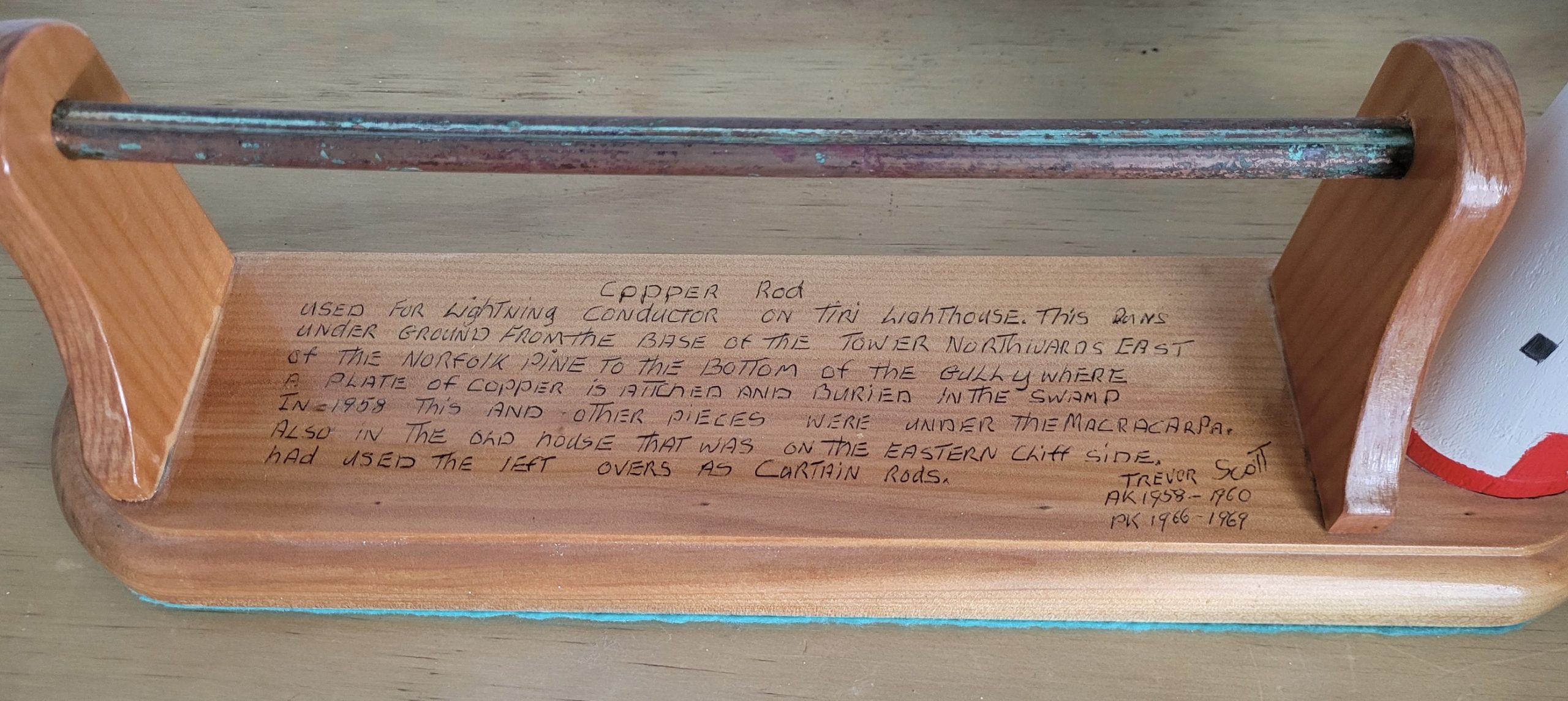

Copper Rod

Copper Rod

Author: Trevor Scott

Header Photo from the archives, pre 1971Date: March 2024

Did you know that lighthouses are often struck by lightning? To prevent damage caused by these strikes, lighthouses are equipped with metal poles called lightning rods. These rods are attached to a thick copper wire that runs from the top of the lighthouse down to the ground. When lightning strikes the tower, it enters through the lightning rod and travels down the wire into the ground, minimizing potential damage.

Trevor Scott, who was the lighthouse keeper on Tiritiri Matangi from 1958-1960 and 1966-1969, shared that he remembers seeing the spare left over copper rods used to hang up curtains in the lighthouse keepers house.

Trevor Scott has writtenCopper Rod

Used for lightning conductor on Tiritiri Lighthouse. This runs under ground from the base of the tower northwards east of the Norfolk pin to the bottom of the gully where a plate of copper is attached and buried in the swamp. In 1958 this and other pieces were under the maracarpa. Also the old house that was on the eastern cliff side had used the left over as curtain rods.

Not your average Tuesday on Tiritiri Matangi – or maybe it is!

Not your average Tuesday on Tiritiri Matangi – or maybe it is!

Author: Grant Birley. From his second visit to the Island and his first overnight stay.

Photo credit: Grant BirleyDate: 20th March 2024

My Tuesday morning on the island started like any other morning on Tiritiri Matangi. Up early to get out into the bush to enjoy the dawn’s chorus – it truly is a sound to behold! Then it was back to the bunkhouse for a quick breakfast and coffee, a little breakfast chat around the table and then off on what was going to be a very busy day! The forecast wasn’t great with predictions of rain coming through but that was not to deter my plans of walking around the entire Island! I started at the Bunkhouse and went up the East Coast Track all the way to the Papakura Pa and then back along the tracks that hugged the Western coastline. While it was a long day, it yielded some great sightings and a few special captures too. I absolutely loved the variation in flora and fauna at different stages along the island.

My photography goals on the island were two fold. Firstly, in the day, to traverse as much of the island in search of the incredible bird and wildlife that call Tiritiri Matangi home and, secondly, to capture and experience the magic of the night that has become synonymous with this island, from the very elusive and incredibly special creatures who wander the night like tuatara, kiwi and giant wētā to the incredibly dark skies that are found here. Capturing the new milky way core rising high up into the sky above the lighthouse which will then, hopefully, be followed by an incredible sunrise was one of my main goals for the trip! To capture this and more, sleep and rest were merely afterthoughts!

On this specific Tuesday the Island had one more surprise up its sleeve! Talia had mentioned that on their swim the night prior to our arrival, that they had come across bioluminescence in the water when they went for a swim. However, it was only visible when the water was disturbed! I tried finding some for two nights and came up empty handed. While there might’ve been in the water, for me, I prefer capturing this phenomenon on its own terms and so unless the colour occurs naturally, I do not capture it. I am happy to play in it though on those occasions!

On our last evening on the island, two volunteers Jon and Kath joined me for a walk to see if we could spot some kiwi and tuatara. I also had a feeling that it might pay to head down to the wharf and Hobbs Beach just to have one last look if any bio was around and making its presence known. On our way there we bumped into three kiwi – one adult which wandered around us for a little while and who eventually disappeared into the bush. We decided to sit and wait to see if it came out again. A few minutes passed and all of a sudden we heard quite the commotion coming from the same direction the kiwi disappeared into the bush. The bush was too thick for us to see what was going on but soon after, this very young and small kiwi came wandering out and into the open. It walked straight up to us, mulled around for a short period and then moved on past us and into the bush on the opposite side. It took us a few minutes to appreciate what we had just seen and all 3 of us looked at each other to confirm we were all seeing the same thing. That interaction and experience in itself was enough to yield our walk a success, however I still felt the need to go have a look see down at the waters edge. We then bumped into another kiwi on the Wattle Track on our way down although this was a short-lived interaction as the kiwi moved away from us and into the bush. When we arrived down at the wharf it was just on high tide, the wind was blowing in off the sea making it a little choppy. As we walked up to the wharf we switched our headlamps off and I could immediately see blue shimmers on the surface of the water and every so often a flash of blue in the waves crashing on the beach. I raced along the waterfront to see if there was any a little further down closer to Hobbs Beach and sure enough there was. Not much and quite infrequent but enough to get me excited. I decided at this point to make a very speedy return to the bunkhouse to collect my camera gear – you see I left the bulk of my gear behind as the idea of the walk was not of photography but more to enjoy the experience without the pressure to capture images. By the time I had returned the tide had turned and was on it’s way out. The wind was still up and it was starting to rain – albeit very softly. Each time the rain started we seemed to have a burst of blue. It wasn’t long before the wind died down and the outgoing tide turned from some nice, small sized waves to very flat! I thought that was it – there was not enough water movement to stir it up! But, if you know me you will know I don’t give up easily and I have also learnt a thing or two about this stuff – mostly that it sings to its own tune and no matter how good you think you are, it is impossible to predict what it is going to do. I was beyond excited when I realised the “blue show” was starting to kick off as the tide moved out and as it went out so the blue started making it’s way down the shoreline from the wharf to Hobbs Beach. I followed it along the coast chasing the more vibrant sections as they popped up.

It was incredibly vibrant and visible to the naked eye and what my camera was capturing was in fact the same as what I could see. At times, the “sparkles” resembled scenes from Avatar or Moana with entire areas glistening in blue sparkles! Rocks seemed to come alive with “blue glitter” at times!

It was beyond incredible. I spent the entire evening moving up and down the shoreline capturing the blue as it would kick off until eventually, just like that, it disappeared in the blink of an eye. By this time the tide was super low and apart from very feint and infrequent shimmers here and there on the surface of the water, you would not even know it was or had been there!

After packing up and still being on cloud 9 I decided I would still try find a tuatara and so set off with that in mind albeit close to the break of dawn at this stage. No more than maybe 10 metres from where I started my walk back I came across my first tuatara for the night. On the edge of the bush line and beach, it scampered into the undergrowth when I got close – I had originally not even seen it and it was only the noise of it scurrying that caught my attention. I was then fortunate to come across several more as I walked to the end of the Hobbs Beach track. Having seen several I decided it was time to head back as it was impossible to have more luck! Boy was I wrong! As I got to where the Hobbs Beach Track opens up into the wharf area something caught my eye and right there, in the open stood another kiwi. Again, it is one of those moments where for a split second you second guess yourself until the message from your eyes to your brain registers! I stood dead still and let it go about its business as if I was not there. I got to spend a good amount of time with this one and even got to follow it slowly down the track until it moved off deeper into the bush! Believe it or not I saw several more kiwi on my walk back to the bunkhouse as I was trying to get back to the lighthouse to capture some pictures of the break of dawn and sunrise. A quick trip back to the bunkhouse followed to drop off all the gear and then back out to find a spot to sit and listen to the dawn’s chorus as the sun begins to rise! To round off the perfect evening/morning, it was back to bunkhouse for breakfast and a well deserved coffee!

My Tuesday had quickly become my Wednesday!

As I said, sleep and rest were optional and by all accounts an after thought!